As Labour Sleeps, the Greens Are Awakening

Corbyn held back the Green tide. Starmer has opened the floodgates.

by Ell Folan

2 August 2021

In May 2015, the Green party of England and Wales was on the verge of a breakthrough. Caroline Lucas had just been re-elected, becoming the first British MP from a small leftist party to be re-elected since 1945; the Greens had won their highest-ever vote share (4%); the party had come a close second in Bristol West; and they had over 60,000 members (up from 14,000 just three years before). The stage seemed set for a Green surge.

But it didn’t materialise. Jeremy Corbyn became Labour leader, won the backing of left-leaning voters, and the Greens performed poorly in every election until mid-2019, when their pro-EU stance resulted in a brief revival. By the end of 2019, though, the revival was over – in the general election, the Greens polled a derisory 3% and gained no seats. Most notably, Bristol West remains far out of reach for the Greens: in 2019 they lost it to Labour by a 37-point margin.

If Corbynism held back the Green tide, Starmerism appears to be reopening the floodgates. Despite Britain’s departure from the EU, and the end of any prospects for stopping Brexit, the Greens have once again begun to make gains in polls and elections. And unlike in 2019, this Green surge shows no indications of fading.

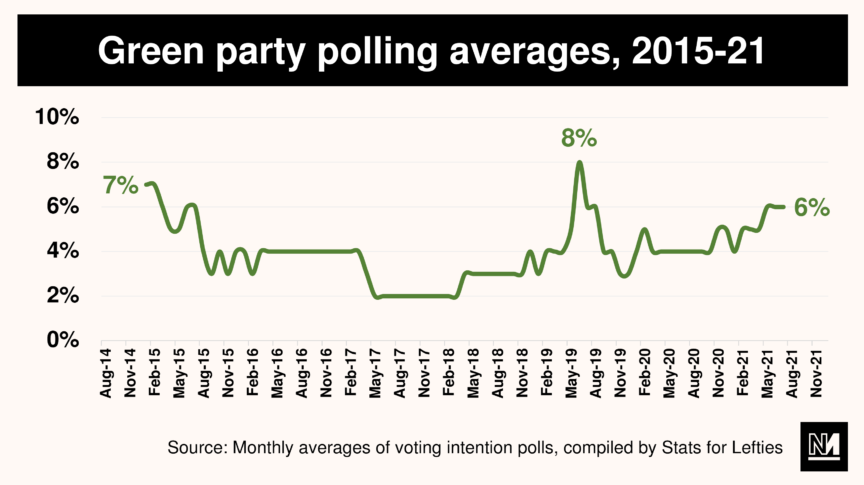

Since the start of 2021, the Greens have risen from an average of 4% in polls to 6%. This is the party’s best performance since June 2019, when they polled 8% in the aftermath of the EU elections. Excluding those unusual circumstances, you have to go back to February 2015 to find a better performance (7%) than now.

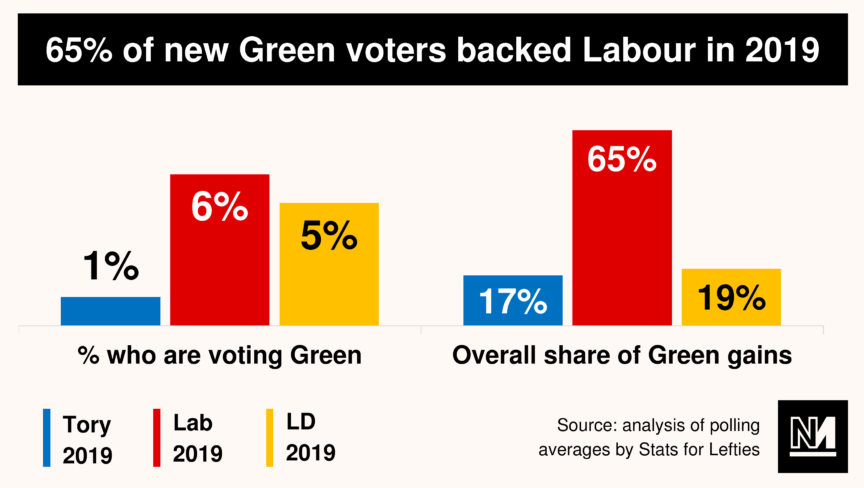

But where are these gains coming from? Mostly, they’re coming from people who voted for Corbyn in 2019. Compared to 2019, the Greens’ poll average is up by 3 points – and 65% of that 3-point increase (2 points overall) has come from people who backed Labour in 2019.

These lost voters should seriously worry Starmer and his team. In a close election, these voters could make all the difference. In 2019 alone, the Green vote was larger than the Tory majority in 12 constituencies, including Kensington, Stroud and Durham North West – and that was with the party winning less than 3% nationally. If they win closer to 6 or 7% in the next general election, Labour will be in real trouble.

Still, these are just polls. The Greens’ results in actual elections indicate that their surge is real and sustained.

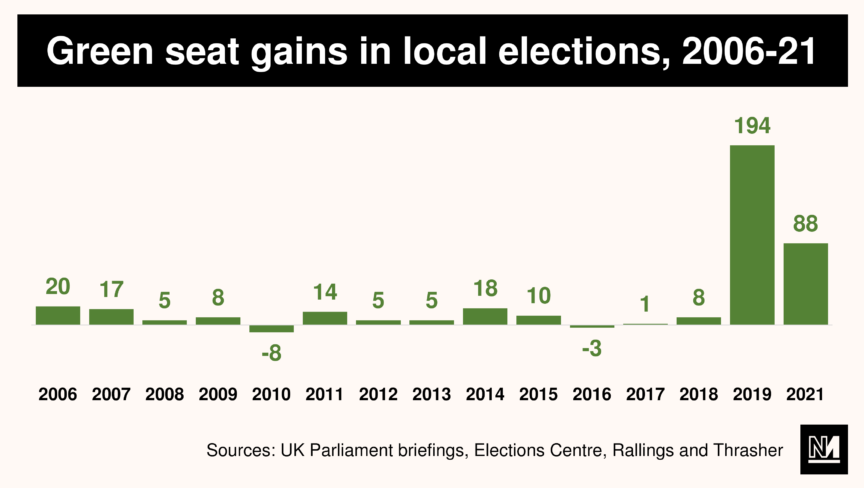

Until 2019, the Greens had never made more than 20 net gains in local elections. In 2021, they made 88 net gains – indeed, they made more net gains in 2021 alone than in every election between 2006 and 2019 combined.

The numerical amount of the gains is not the only notable fact, though. The geographic spread of the Greens’ gains has broadened too. Even in 2019, just 15% of the Greens’ gains were in the north of England; in 2021, 27% were.

In addition to this, data from Britain Elects shows that 49% of the party’s gains in 2021 were in wards that had previously voted Labour, 43% in previously Tory wards. Both this and the regional data suggest that the Greens have a broad appeal that reaches across political divides and regions.

But gains in elections for relatively powerless local authorities don’t always translate into success in elections for the UK Parliament, as the Lib Dems found out in 2019. What does indicate potential Green growth, however, is their success in elections for powerful executive figures in 2021: Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) and Mayors.

The party’s best result was in Bristol, where the party finished second in the city Mayoral election and won 44% in the final round. This was the closest that the Greens have ever come to winning a Mayoral election, but it wasn’t the only place they did well.

In the West of England Mayoral region, Green candidate Jerome Thomas won a stunning 22% of first-preference votes (+11), whilst the party won 9% in the West Yorkshire Mayoral election and over 10% in six other PCC areas. In Dorset’s PCC election, the Greens came third with 14%, out-polling both Labour and the Lib Dems.

Their improved performance in these contests, in one case coming close to winning, suggests that more and more voters are willing to entrust the Greens with actual power and not simply treat them as a protest vote. For the first time ever, the Greens now lead two local authorities in England and Wales (Brighton and Lancaster), and they won the most votes in Bristol in 2021. The party is not only winning protest votes from dissatisfied Labour voters – it is also winning power and implementing its policies in areas across England.

However, there are indications that the Green surge may be slowing down. Two areas of disappointment for the Greens in May 2021 were in London and Wales.

In London, despite polls indicating that they might win double their seat total on the Assembly and win up to 10% in the Mayoral election, the Greens ultimately only gained 1 seat on the Assembly and increased their Mayoral vote by just 2 points. In the Welsh Parliament election, meanwhile, the party’s vote share rose to 4% but they once again won no seats despite the proportional electoral system.

There are still very few areas outside of Brighton where the Greens might gain parliamentary seats. In Bristol West, where the Greens almost won in 2015, Labour has a majority of over 28,000; in Stroud, which the party targeted in 2019, the Greens trail Labour by 23,000 votes; and in Norwich South, which was one of the party’s top seats as recently as 2010, the party didn’t even save its deposit in 2019!

Despite this, it is inarguable that the Greens are growing fast, and that this should concern Labour. From Bristol to Knowsley, in many places the Greens have emerged as the primary opposition to Labour; a majority of their gains in 2021 were from Keir Starmer’s party. Not only that but their improvement in voting intention polls is overwhelmingly driven by dissatisfied Labour voters who are unhappy with Starmer’s leadership, which could turn several seats in university towns and cities – such as Bristol West – into marginals. Voters are now trusting the Greens with power and are increasingly keen to see their candidates elected as Mayors and PCCs.

Still, I am convinced that Labour can win back the voters that it has lost. Polling indicates that left-wing policies, as articulated by Corbyn and now by the Greens, are very popular. By putting forward a positive vision for Britain’s future, Starmer can still appeal to the voters that are abandoning the party under the leadership of Keir Starmer. Recent announcements on trade unions and labour rights suggest that the leadership is beginning to understand this. Hopefully it will continue to do so.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties and a columnist for Novara Media.