Changing Your Mind is Good, Actually

Political convictions: good. Admitting you were wrong: also good.

by Rachel Connolly

9 July 2021

There is a certain kind of person (we all know a few) who tells stories about the things that happen to them in a specific way. They are always the hero, bravely battling adversity, unfairly maligned in every environment they enter, constantly set upon by toxic friends, backstabbing colleagues and terrible housemates. Riddled with misfortune, they are forever involved in a scrape of some description, yet apparently never at fault. You hear one of these types tell a few stories like this and you start to see the pattern and realise you should take everything they say with a handful of salt.

It is an unseemly way to carry on. And, like every ugly trait we notice in others, the most unpleasant thing about it is the mortifying sense of recognition it prompts. We all have some of this person in us, in the form of an inflated sense of our entitlement to be treated with deference; a powerful attachment to our own perspective at the exclusion of competing views and evidence; a quickness to feel aggrieved if challenged or ignored; and a stubborn attachment to bad ideas and wrong positions that we often don’t even have good reasons for holding.

Which brings me to the underrated pleasure to be found in changing your mind. Stubbornness is natural and instinctive, I think. But that doesn’t make it an admirable trait, or even an enjoyable way to operate. There is something freeing about admitting to yourself you were once wrong about something, and in seeing the views you hold as changeable, rather than as an extension of yourself.

To have been wrong about something is to have really thought about it, to have been flexible and challenged yourself and accepted your reasoning as fallible, and more than that, as flawed. Which is to say that to have been wrong is to have been honest with yourself. But how often do we think of it this way? How often instead do we let pride cloud our thinking, and dig in our heels when presented with new information? Or when it turns out we have misunderstood something? How often, when a certain view becomes unfashionable, do we simply pretend we never held it? Or act like it was something forced upon us?

We all form views on certain topics without knowing very much about them; everyone is busy and life is short. But we can become overly attached to these views without accepting to ourselves how arbitrary they really are. This is true even for those of us who consider ourselves politically engaged. In a piece for the New Yorker a few years ago, Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds, the writer Elizabeth Kolbert described the wide array of psychological research demonstrating that “reasonable-seeming people are often totally irrational”.

People experience genuine pleasure—a rush of dopamine—when processing information that supports their beliefs. “It feels good to ‘stick to our guns’ even if we are wrong,” researchers say. https://t.co/Wf8UEHdNVf

— The New Yorker (@NewYorker) July 1, 2021

Kolbert explained how researchers think that humans are so used to collaborating with each other and sharing knowledge (a behaviour that has been beneficial to us since the days of hunter-gatherers) that we outsource our understanding of everything, from how toilets work, to politics, onto people we trust. The result is that we are often blind to just how little we know ourselves. The researchers she cites, Steven Sloman, a professor at Brown, and Philip Fernbach, a professor at the University of Colorado (both cognitive scientists), call this the “illusion of explanatory depth”, since we are often labouring under the illusion that we can explain topics or phenomena much better than we really can.

Anecdotally, this is everywhere in politics. Most of us assume our views on a topic will match those of our more engaged or better read friends, a politician we trust, or a commentator we consider to be authoritative. Identity politics, too, is sort of premised on this; people from one identity group rely on the opinions or views of one person or a small group of people from another identity group as a proxy for the views of that group as a whole, or a substitute for reading around an issue. Everyone does this; I do it all the time. But maybe if we were more mindful of the tenuous foundations of many of our political positions, we would feel less committed to them and more open to receiving new information and having our minds changed.

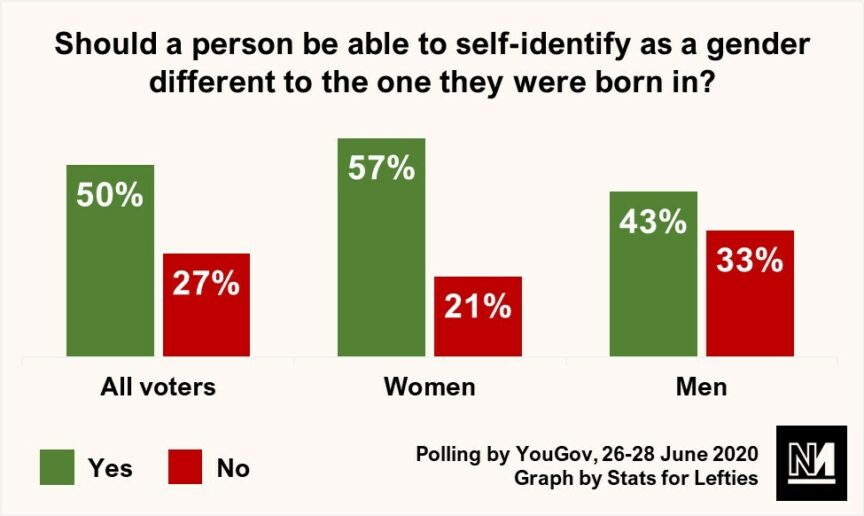

We can see an example of the problem with outsourcing our views (in the identity politics context) in the ongoing argument over trans rights. This argument is often pitched as a row between cis and trans women, or feminists and trans women. But the reality is that it’s only a small group of cis women who hold gender-critical views – the rest are either actively in favour of trans rights or don’t know anything about this argument and have no views on it one way or another. A recent YouGov poll, for example, showed that 57% of women think a person should be able to self-identify as a gender different to the one they were born in, while only 21% of women think they should not.

From personal experience, the myth that these views are widespread among women seems to have imbued them with extra authority. Men who rely on gender critical arguments often frame their own position as the view of women or feminists, when they are really only in agreement with a small subset of either. It is completely bewildering, as a woman, to be told by a man, or even another woman, that your own views are wrong because they are not those of women. Lived experience can be a useful form of knowledge, but we should be aware of its limitations; people of any identity group can be outliers, wrong, cynical, lie, have bad politics, or operate from a position of pure self-interest.

So many political arguments, particularly in online spaces, are much more about appearing to be right, or good, than about actually trying to be those things. It is rare for anyone to approach a topic with an open mind, there is so much bad faith and projection over opposing viewpoints, and nobody wants to be seen to cede ground. But recently I was called for jury service, a rare environment where it is expected that at least some people in a group will have their views changed by discussion (or nobody gets to go home) and the style of conversation was very different. Some people were rude and obnoxious (some people always are), but others would admit when someone else’s viewpoint had made them see a piece of evidence in a different way. People let their minds be changed.

Political conviction is a good thing; views which change constantly are indicative not of thoughtfulness but a lack of integrity. But a person who never changes their mind is likely to be wrong a lot of the time. As Bob Dylan sang: “Half of the people can be part right all of the time. Some of the people can be all right part of the time. But all of the people can’t be all right all of the time.” I don’t know anybody who is right all the time – certainly not me.