What Can We Learn from the Existence and Eviction of the Calais Jungle?

by Brush&Bow

10 November 2016

As the Calais ‘Jungle’ eviction filled the headlines with images of destruction, confusion, and desolation, it was easy to forget that Europe’s largest unregulated refugee camp had been home to nearly 10,000 people, and thousands more had passed through.

To challenge the mainstream media portrayal of the Jungle as only a muddy, desperate environment without basic facilities or official authority, it is important to highlight what was built there, and to recognise the strength, resilience, and determination of people to create homes, an economy, and hold onto their autonomy in the worst possible conditions.

There have been refugee camps in the Calais region since the early 1990s, and after each eviction people have always come back, to rebuild and start again. Calais and Jungle residents alike are unanimous in the belief there will always be migration at the border, that people will continue to arrive and try to cross to the UK. In light of this, the eviction does not appear to be a sustainable solution; rather, with the upcoming elections in France, this reflects on political, not practical interests.

It is true the unregulated, lawless nature of the Jungle led to a high risk of human trafficking, violence and a hard drugs market. Basic infrastructure such as electricity and water was limited, access to building materials was restricted, and many shelters were inadequate. Smugglers and criminal activity filled the void left by the lack of any official authority in camp.

However, as the Jungle comes to an end it is also crucial that we do not just write it off as a terrible by-product of EU border policies, but rather see what can be learnt from the camp and how can this can be integrated into the way Europe supports refugees and asylum seekers.

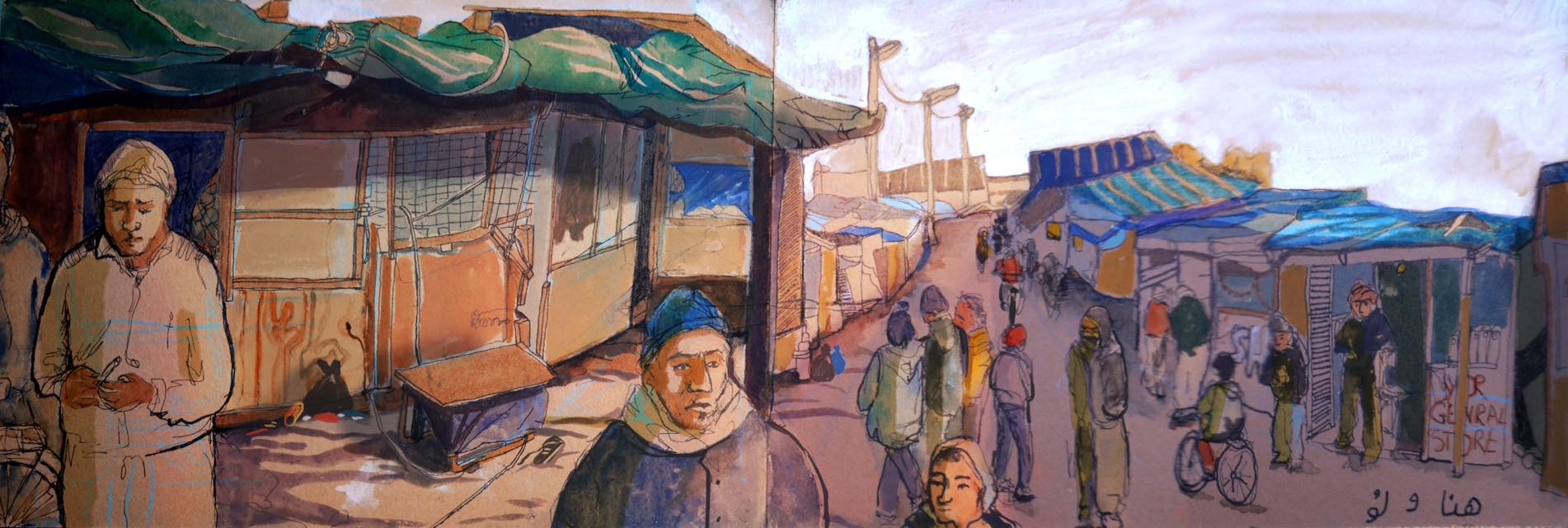

Unlike other refugee camps where food, shelter and facilities are made available by the authorities, in the absence of any official authority in Calais everything had to be provided by residents or volunteers. Before the bulldozers arrived, the Jungle was host to around 70 restaurants, shops, barbershops, and community spaces. All structures were handmade by refugees, volunteers and activists, from any materials people could get their hands on.

Far from just existing as thriving spaces of commerce, these structures were safe spaces where people could gather to share information and make plans. In an environment so far removed from anyone’s idea of what constitutes a normal life, being able to go to a restaurant or a barbershop and see a friendly face offered a rare moment of normality amid the chaos.

‘Sami’ was one of these restaurants, run by a group of young Afghani men, on the muddy main street of the Jungle. Decorated in colourful fabrics, furnished with mismatched chairs and tables and overlooking a small lake, inside you could almost forget the dreary surroundings of the camp. People would come to charge their phones, gather information, and eat together, food full of the flavours of Afghani home cooking.

After their long journeys people were greeted in places like Sami by members of their own community, who rallied around to help newcomers find a place to sleep and some food.

While the right-wing media has gone all out to perpetuate the dogma that refugees and migrants are an economic burden, countless examples such as this prove when people are given a chance, they are willing and ready to work in ways which are beneficial to both the host community and the individual. People are entrepreneurial; in the Jungle, these businesses were started from next to nothing.

Tofan, an Afghani whose name means ‘storm’ would often be found in the Sami restaurant, sitting cross-legged with his shisha pipe and chatting about evenings in the Jungle restaurants when people would gather with musical instruments and sing songs of hope and home.

“We don’t need all these charity handouts, waiting in line for food, what we need is music! It gives us a moment of freedom.”

Evenings in the Jungle were often filled with music, especially at times of celebration, when a friend makes it across the England, or to mark festivals celebrated by the many Muslims living in the camp. The sanitised state camps fail to provide spaces for moments like these, when people can feel connected with their community and celebrate their culture.

Historically, so many genres of music have evolved from migration and movement of people. Greek refugees from Turkey in the 1920s brought with them Rebetiko, and blues music grew from the forced movement of African slaves across to America. These examples highlight an often-forgotten benefit of migration; people bring with them new melodies and memories which contribute to the way that we express ourselves and understand each other as human beings.

We spent one Eid in the camp, more than a year ago. In a dimly lit tent a group of Sudanese men sat in the communal space, which they had built themselves, with a guitar and a drum. First, the beat of a drum followed by the tinny tone of the guitar. One man started singing, smiling, his head tilted upwards with eyes closed. The songs were part of every man’s memory, and they joined in, clapping, singing in harmony, rising to dance. Far from home and family, these songs transported them back there momentarily.

Alongside offering a kind of practical support, the restaurants and other autonomous spaces were places of community, pride and culture. This kind of support is something which the European asylum system, in all its impersonality and bureaucracy, lacks. The experience of being a refugee is difficult on many levels, but an aspect which is often ignored is that it can challenge people’s place in society, national identity and pride.

The respect of human dignity should be fundamental to Europe’s asylum process, but instead people who have experienced torture, war and loss are simply ‘processed’ and sent to integration courses, to form a new identity in their host country. Whilst integration is without a doubt necessary, it is a one-way integration with very little attention given to the individual, and the skills, culture, perhaps even trauma, that people carry with them to Europe.

Within the Jungle there existed a sort of preview of the conditions people could expect after the eviction, in the form of an official container camp right in the middle of the site. There were no aspects of community, solidarity or self-organisation to be found in this fenced off section of the camp; people were forced to give their fingerprints to access the area, separated from their community and support networks, and completely dependent on charity handouts.

Additionally, there were many people living in the Jungle who were in various stages of claiming asylum in France, even some who had received their papers. The fact these people remained reveals failures in this process on multiple levels. In many cases the state has failed to provide people with housing and support, but some people were actively choosing to remain in the Jungle. The only possible explanation for this can be that the Jungle offered something that the official system cannot: community, mutual aid and autonomy.

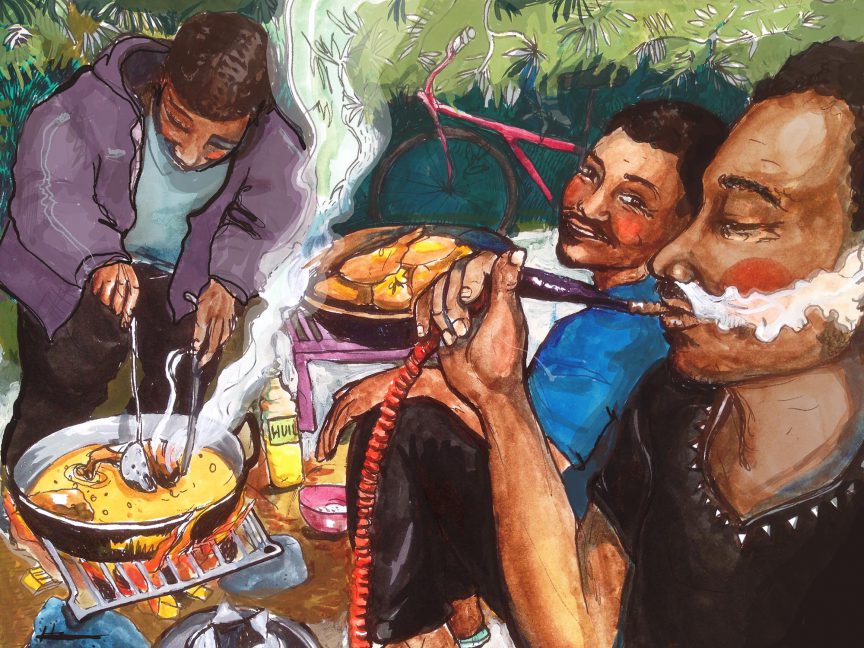

The above image illustrates a party in the Jungle to celebrate Abdul, a young man from Sudan, receiving his asylum papers in France, giving him legal residency for ten years. Far from sparking feelings of resent or jealously, the atmosphere after one person succeeded to get papers – or make the crossing to England – was one of communal victory. Abdul’s asylum party was a celebration for the whole Sudanese community. They smoked shisha, roasted enough chicken for 30 people over the fire, and played music late into the night.

Abdul spent his entire asylum process in the Jungle; the state provided him with no accommodation or financial support. The community that surrounded him in the camp offered support in so many ways that after receiving his papers he was content to stay a little while longer in the Jungle whilst slowly making plans to move out. Like many others who now live in apartments in Calais, he would still come back to the Jungle most days to visit his friends and family. Now, they are scattered across France.

As the homes and community spaces of the Calais Jungle were razed to the ground, over a hundred unaccompanied minors found themselves sleeping on the streets. After waiting in line for three days, they were told there were no buses for them, and were given no information about what they should do next. Over a thousand other children were left alone for a week, sleeping in the container camp. Meanwhile, French authorities declared that the camp was “empty”, and that the eviction had been a “success”. Already, new arrivals are turning up to find a bleak, desolate patch of land with no infrastructure or community to support them.

Instead of complete destruction, the only option considered by the French authorities, there were so many other ways that people could have been resettled and relocated while upholding their dignity, rather than completely violating it by destroying that which they had worked so hard to build. This illustrates yet again the gulf between policy and the lived reality for people on the ground that characterises the European asylum process.

If there is anything the Jungle can teach us, it is that people are resilient, and capable, but they need their communities in order to be able to thrive. Mutual aid, collective solidarity, and cultural pride – three concepts which were so strong in the Jungle, and are so lacking in state provided shelters.

Given the fact that there are already new arrivals in Calais, it appears that the eviction is not discouraging people from coming and trying their luck at this border. One Jungle resident sums it up particularly concisely:

“Migration will never stop, and people will always gather at and move across border. Building higher walls will never stop this! You can build it a bit higher but people always find a way to go through. So why do they put so much money into a solution that doesn’t work? You might as well build solutions which are profitable, such as putting money into creating homes and jobs. Around Calais there’s so many empty structures, factories, and there’s so many people here with skills. It doesn’t make sense!”