Two Months Under the Executive Order: Whiteness, the Muslim Ban, and Me

by A Revoked Migrant

26 March 2017

This is a personal (and political) account of what it’s like to be affected by the Trump Administration’s two successive Executive Orders attempting to ban travel from 7, and then 6, Muslim majority countries – and the ensuing climate of Islamophobia and mistrust in the State Department. Novara Media has anonymised this article in order to protect the author’s ongoing visa applications.

‘Hmm. What an interesting name… are your parents… let me guess, Lebanese?’ Taken aback by the immigration officer’s tone, somewhere between curiosity and hostility, I responded, ‘No, my father is from Iran. My name is Persian.’

I am a British-Iranian, I was born, raised, and have lived in the UK my whole life, up until moving to the United States for graduate school. I spent my childhood visiting Iran, and as a foreign student thousands of miles from my family I found a real sense of home living alongside Iranian-American communities.

Iranian-Americans make up a population of 1-2 million and rising in the United States. From the gated communities of Palo Alto and Beverly Hills to San Diego, the Iranian diaspora has established a culturally distinct – and distinctly bourgeois – presence, especially in California. This community include some of the wealthiest waves of immigrants to ever come to the U.S. There is even a neighbourhood in West Los Angeles known as ‘Tehrangeles’, that hosts boulevards of nothing but Persian eateries, shops and schools. In 2010 it was officially approved by the City of Los Angeles as ‘Persian Square’, as it is indistinguishable from walking through neighborhoods in Tehran. The economic advantages of the community has assumed a sense of exemption from the discrimination poorer immigrant communities often systemically incur, such as the regular immigration raids that have disrupted the lives of Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities on the East Coast. The symbolic message of the executive order on the 27th of January, and a revised order on the 16th of May (successfully blocked, for now), have had tremendous effects on the lives of these American families, and migrants from all over the world with ties to the targeted nations. The orders have shown that being rich and successful are no protection against racism. You might have all the material trappings of whiteness, but that doesn’t make you white.

Rejected; Other

This is a revoked migrants story.

I received an approval for work authorization in the form of a visa from the department of Homeland Security. In early January I flew back to the UK in order to have the US Embassy rubber stamp my case, and have the visa officially printed in my British passport. I had been through this process twice before, after being granted a student visa, and then to complete a year of ‘Optional Practical Training’; which is essentially work authorization automatically granted to foreign students who graduate from a US academic institution. It was by recommendation of my school, and an immigration lawyer, that if I wanted to continue working in the US, I should apply for a new work visa as a change of status within my OPT year. That is exactly what I did.

When I came to have my interview however, I was shocked to encounter a hostile line of questioning that had previously not been the case. Learning of my Iranian connection, the officer immediately put down my papers, frantically typed something onto his computer and left me at the interview booth without saying a word. Returning with a supervisor, who then asked me for more evidence of my case and certain documents I did not have access to. This was very confusing as I was not instructed by my lawyer to take a copy of the 300+ page document—that was my application—as it should have already been uploaded onto the USCIS system, that the immigration officers at the embassy should have access to whilst they conduct interviews. Moreover, none of what the officers were asking for were included on the embassy’s recommended documents list to bring to an interview, either. Yet, I was being asked questions like, ‘Who told you to apply for this particular visa?’ Followed by, ‘We don’t think you actually qualify for it… this visa is only applicable to, for example, people who work in xyz scenarios.’ Firstly, the reference to a number of career paths that did not follow my own really threw me. I had already clearly explained why I qualified for the visa due to my work and experience. Secondly, I was completely at a loss as to why I was being asked to defend my case in this very instance, as I believed my case had already gone through all the necessary scrutiny and thus my approval notice had been granted accordingly. I very quickly understood the hostile treatment to be a clear attempt to gaslight my approval, and application, that clearly proved my work (academic and otherwise), accolades and achievements and ability to be awarded the visa.

I left the embassy with a note with the title ‘Rejection’, alongside a handwritten note and ‘other’ boxed ticket, accompanied by an explanation that my case required further scrutiny and administrative processing. Under what grounds, I was not told. They were therefore going to keep my documents and my British passport during this time. I was advised not to contact the embassy, but to login to an online portal to check my status. I did this. I did this every day for 42 days, and counted every one of them, before I received any response. The average turnaround is 5 days.

In this wait period a lot was changing in America. From my parents’ home, I watched the inauguration of a new president. After five days in office, I watched as the announcement was made regarding an executive order, posed under the guise of national security, directly banning the entry of nationals of seven countries. I was not shocked to discover Iran’s place on that list, given the new administration’s very public Iranophobia. Trita Parsi the president of the National Iranian American Council explains ‘Trump built on and rode the wave of a project that has been years in the making. While there can be no mistaking Trump’s contribution to this project, Trump is nothing but the most outward symptom of an affliction that has long plagued our country.’ He notes the fuel and growth of this plague, claiming there are many, that have sought to push a rhetoric that treats the entire Muslim world as a threat to, what he calls, the ‘ordinary American’. He aims to call out those who pushed for war with Iraq and similarly those who continue to push for war with Iran. His ‘parade of horribles’ includes ‘the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), The Israel Project (TIP), Secure America Now, and United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI) and propagandists like Michael Rubin, Eli Lake, Adam Kredo, and Josh Block.’ We can thank the work of these organizations and individuals in ‘connecting Iran (and Iranians) with terrorism that the identification cannot come unglued; by characterizing Iran (and Iranians) as medieval religious zealots so as to deny them the humanity we reflexively accord all others.’ The results of 2015 Pew Research Center poll, on ‘World Views of Iran’, only bolsters Parsi’s claims. In it, a whopping 76% of Americans voted as viewing Iran as unfavorable, with only a remaining 14% viewing it favorably.

Check it right, you ain’t white

Iranians are the national group most affected by the executive order. US census data in 2014 extrapolated that there were an estimated 1-2 million Iranians living in America, with the largest concentration, upwards of 70/80,000 residing in Southern California. It is the largest presence of an Iranian population and diaspora outside of Iran. These figures however have been somewhat contested, as it did not include children of immigrants and those who did not identify with the racial categories offered. There was, after all, no clear category for Iranians. Leading to the belief that there may indeed be many more not counted for. The “Check it right, you ain’t white,” movement of the 2010 census urged Arab and Iranian-Americans to explicitly write in their ethnic identification instead of checking the box for ‘White,’—as most forms generally ask those of ‘Middle Eastern’ descent to do—was largely ignored, as more often that not Iranian-Americans find it easier and safer to choose ‘White’. Furthermore, given that the vast majority of the diaspora left Iran during, or soon after, the Islamic revolution of 1979, that coincided with the hostage crisis, in the wake of which anti Iranian sentiment spread across America.

An anti-Iranian protest in Washington, D.C., 1979

This sentiment further propagated the fear of many Iranians to disassociate with their country of origin, and instead hide behind other more popular immigrant categories or ‘Whiteness’ as a safeguard. Maz Jobrani, an Iranian-American comedian summarises the issue in a comedy sketch in which an Iranian is questioned by a census bureau official: ‘What is your race?’, ‘Oh! I am Italian!’

I checked the online portal: ‘Date: 27th January, case changed.’

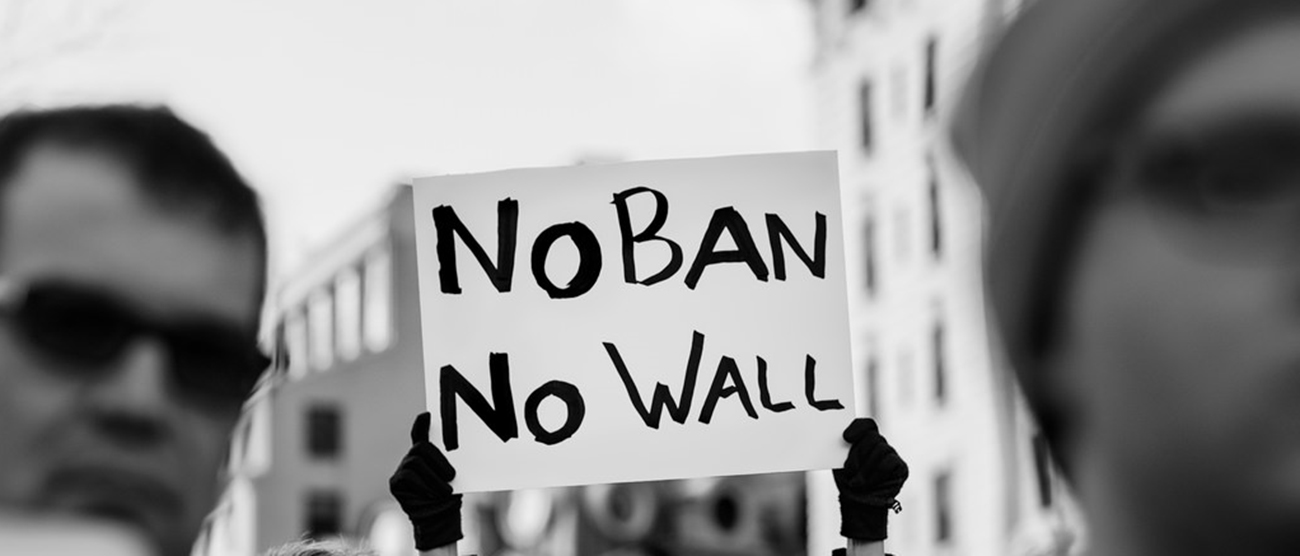

After this initial ban came into effect, I was shocked to notice the chaos it created at airports, those it affected already in transit and the solidarity protests across the US. What I was most shocked by however, was the need for many members of the Iranian diaspora to come out as defiantly stating sentiment along the lines of, ‘Just because I am Iranian, does not make me Muslim’. I found this deeply misguided. In any other instance, I would have understood and supported such a claim; after all I am Iranian with no religious grounding or practice. Moreover, I do not discredit that there are Iranians of B’hai, Jewish, Christian and Muslim faith as well as those who are non-religious, that all have active communities both within the Islamic-Republic of Iran as well as in the diaspora. The need, however, to disassociate with the Muslim community—as if it somehow makes you a different, or rather a better, Iranian—in a time of rife Islamophobia I found profoundly disappointing and irresponsible. It is a common assertion that diaspora Iranians make, that they should not be targeted by racial profiling or discrimination because the diaspora is by and large majority non Muslim and non religious. As my father always used to say, I am only Muslim by name, but not by any other marker. Of course, however, this can only be understood alongside the implicit argument that it is only practicing Muslims are the ‘real threat.’ Which is the exact foundation that Islamophobia thrives off.

The Land of the Aryans?

What I feel this points to is a rift in the Iranian community itself, that pertains not only how they identify within religious grounds, but too, with race. The notion that there are somehow ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Iranians—the ‘good’ being those who left before the revolution, and the ‘bad’ being those who still remain under the conditions of a now Islamic-Republic—does not only echo the Muslim and non Muslim divide, but also an socio and economic one. It is important to note that many that left Iran, for North America and Europe, around the revolution where supporters of the last Shah – Mr Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Alongside this, of course, many were fleeing fear of religious persecution, and others with the common migrant story, simply looking to resettle with the aim of achieving a better life with access to better education, work and opportunity. More to the point, the Pahlavi reign was one that sought out to modernize and ‘Westernize’ Iran. Iranians the in Iran of pre revolution thus tended to identify with a sense of ‘Whiteness’ as a result of the history of race formation and ethnicity developed under this project. Pahlavi’s nationalism insisted upon a racial superiority of Persians above all their Arab neighbors. The notion of Iranians as a people birthed from the Caucasus Mountains may have even made Iranians claim they were more ‘White’ than their European or North American counterparts. Pahlavi’s alignment with racialist White superiority politics espoused by European colonial empires followed that generations of Iranians where to be proud of their Aryan heritage, in direct contrast to the Arab, and with it, Muslim invasion of the 7th century BC. Related is the myth that Iran literally means the ‘land of the Aryans’ . The myth propagated by Max Müller, who claimed in 1862 that the term airyanem vaejah found in the Avesta is the ancestor of “Iran” and means the “Aryan expanse.” This myth has become so widespread that serious scholars propagate it even to this day.

What this does, is ignore that Iran is, and has been, a multi-ethnic nation of Persians, Azeri Turks, Kurds, Baluchis, Arabs, Armenians, and many other groups since the Sassanian empire, to the gates of Persepolis, to today. Yet, as Alex Shams notes, ‘Iranians were taught to pride themselves for their Aryan blood and ‘whiter’ skin and to ‘look down on’ the supposedly “stupid” Turks and “backward” Arabs.’ Shams further explains, ‘as educated Iranians widely bought into this European system of racial hierarchy, Iranians began to see themselves as ‘White’ in a global perspective and many carried this identification with them into the United States.’

This was—and is—not only an Iranian problem. In 1923 the Indian man, Bhagat Singh Thind, argued before the Supreme Court that he was descended from Aryans — and so, technically was white, even if his skin wasn’t. His argument was grounded in his societal placing of a high-caste Hindi sect. His case was brought in response to the 1906 law that only allowed ‘free white persons’, African Americans and those hailing from Africa to petition to become naturalized citizens. Singh Thind lost his case and as Lavanya Ramanathan notes, consequently shut the door on many immigrants who’d hoped to similarly argue their way through.

The case was closed on the grounds that a ‘common’, and not ‘scientific’ understanding of what constituted the Caucasian race, aka: whiteness, would prevail. The court argued this ‘common’ understanding of Caucasian vs. the exclusion of non-whites was formed under a ‘common’ understanding of racial difference. Legal markers of racial difference that only afford certain privileges to Whites is nothing new in American history. The Jim Crow laws that followed from the Black Codes of maintained segregation and suppression of civil rights and civil liberties for black people, defined against the white citizenry. Similarly, the one-drop-rule of the 1924 Racial Integrity Act aimed to prevent racial mixing. The centrality of blackness in American conceptions of race is key to understanding how only whiteness affords power in the eyes of the American state, and beyond. This history clarifies why people want to appear white in order to attain all the legal and societal privileges whiteness offers.

Post 9/11, the racialised Other of the Muslim has joined the African-American as the model against which white citizenship is defined. Muslims of course exist in all racial categories, including black people; indeed, the original executive order included three African countries, Libya, Somalia and Sudan. But since the War on Terror, Muslims in the American popular psyche are imagined to be of Middle East descent. This means that one can be racialised as being Muslim, without actually being one, thus becoming subject to state violence, racist profiling or victims of hate crimes eg. the Muslim ban. It is not without coincidence that days after the executive order the 51 year old, white American ex navy vet, Adam W. Purinton, fatally shot at Srinivas Kuchibhotla, 32 and wounded Alok Madasani, 32 at Austin Bar and Grill in Olathe Kansas City, whilst shouting ‘Get out of my country’. He then went to the bar tender and explained he had killed two Iranians. The men were in fact Indian engineers, and their faith unknown.

I’m mixed-race. On the street, you might read me as southern European – blue eyes, brown hair, and even in the summertime only ever the safest shade of brown. But on paper, my Iranian name betrays my status as a racial Other. This liability finally meant that my visa was to be revoked. Under which, once again, I was given no clear indication as to why. I believe it is without a doubt the hostile questioning of my name and ethnicity at the embassy, with the subsequent suspension of the processing of my case after the first executive order, spurred by the new attitude of the administration that has now lead to a revocation. I was racially discriminated against due to my father’s place of birth. An Iranian father who married, and has remained married to my English mother and who has been living, working and raising his family in England for 30+ years. I cannot help but think if this could happen to me, what about those in more precarious circumstances without a family, lawyer and a home to fall back on.

America First

The Department of Homeland Security’s Intelligence document on Trump’s Muslim Ban stated, that ‘Country of citizenship is unlikely to be a reliable indicator of potential terrorist activity.’ With this in mind, hearing the news of revocation, I wanted to scream to the heavens:

Who in the new administration has read their own DHS inquiry? Who knows that the Sasanian empire hailed its peoples from hundreds of tribes and practiced ten different major religions including Judaism, Hinduism and Buddhism, alongside the state religion of Zoroastrianism? It is possible to live side by side. These faiths all remain alive in the region today, even after the coming of Islam. The empires people spoke a dozen languages whilst the court’s tongue was Greek, Aramaic and ancient Farsi. This was the first court to make the harming of a slave a crime, forbidden even for the Shah himself.

With the executive order signed on the 27th of January, and then a revised version on the 6th of March (that was cautiously blocked), you have sent a clear symbolic message that the US considers citizens of certain nations nothing but terrorists. It is a cold hearted, blind sighted attempt to stigmatise certain ethnicities whilst ignoring the many complexities in diversity of religious and cultural conflicts from within the targeted countries themselves. It is an Islamophobic and racially motivated act that is wildly unconstitutional, and arguably has no logical connection to effective anti terror legislation

I grew furious when I heard many other stories of others experiences, that had even started under the previous administration. Countless tales of Indian, Pakistani, Middle Eastern and African friends, who have been falsely arrested, jailed and then released upon the realization that they simply looked like a supposed target. Or under the guise of deliberately imprecise anti terror laws, like this new executive order. What is more frightening is to accept that the Muslim ban is only one portion of a fierce crackdown on immigration. Across the board, tourist, work and educational visas have incurred more scrutiny than before, spouses are no longer able to accompany partners on said visas. The bourgeois intelligentsia, artists and writers have been targeted and incurred hours of interrogation upon attempts to enter the country. The position for working-class migrants and undocumented labourers is more precarious than ever before. We are witnessing the demonisation of movement, period.

‘America First’ is a project to make America white; to pursue a racial purity that has only ever found realization in racist myth-making. To all the Iranians who think claiming disassociation from Islam saves you from being Othered by the state: It doesn’t. It misses the point completely. There is only one common enemy and that is white supremacy. I find some solace now in Hannah Arendt’s sentiment that she was never really a Jew until she was persecuted for being one. Although she was not practicing, she got furious with Theodor W. Adorno for adopting his non-Jewish parent name. Professor Griselda Pollock writes of Arendt’s The Human Condition that, “Every human life is the potential beginning of something new. Unlike animals, which are predictable – each will behave as its parents behaved – something has begun in a human that could be completely different. This is ‘natality’. As a result of that, the human condition is plural.” In that same vein, I will defiantly stand in solidarity to any present hum of Islamophobia and say – I am Muslim. For as the slogan goes, “First they came for the Muslims, and we said, not today, motherfucker.”

Signed,

A Revoked Migrant