What Could a Corbyn Government Mean for Britain’s Foreign Policy in Oman?

by Phil Miller

9 November 2018

Last month, over five thousand British soldiers played a giant war game in the Middle East called Swift Sword 3. The operation took place in Oman, a quiet corner of the Arabian peninsula bordering Yemen, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Its ruler – Sultan Qaboos – has sat on the throne for nearly half a century.

Swiftly after Tory party conference, Britain’s defence minister Mark Lancaster visited the Omani port of Duqm to launch the training exercise. He also opened a new Royal Navy base in Duqm – costing UK taxpayers millions (the full price tag is secret). Just like in Part 1, where we explored British foreign policy towards Bahrain, in Oman it’s clear that the UK is propping up another Arab monarchy.

There’s very little written in English about what Omanis think of British troops supporting their Sultan. So to find out more I caught up with 34-year-old Omani activist Khalfan al-Badwawi, who was tortured in Oman and now lives in exile in London.

Novara: What was your life like in Oman?

I worked as a nurse in intensive care and saw a lot of corruption and injustice in the hospital: to make space in the ward for an Omani Royal with a cold we were made to kick out a patient who was really ill. I eventually left nursing and began working in Health & Safety in Oman’s oil fields. Shell is heavily involved. BP also has a huge gas field in Oman, taking 60% of the revenue. I think the role opened my eyes to risk and questioning the status quo. I worked in Sohar, an industrial city with lots of refineries and an aluminium smelter. It was a huge site with 1,000 employees. The industry is largely made of expatriate workers. Indians and Bengalis at the bottom with white people at the top. Funnily enough, it was my Canadian boss who asked me why there were no trade unions in Oman. We didn’t have any then.

I began writing online, questioning Oman’s politics and economy, using an alias, afraid of using my real as I recalled my father’s stories. In 1971 and 1972 the organisers of labour and student protests were executed in the capital, their bodies dumped with bulldozers and displayed to crush the activist spirit of a generation. I felt I had to dig deeper into Britain’s role, its extraction of Omani oil, and corruption.

Novara: When did Britain first become involved in Oman and what impact has it had on the country?

Britain has a history of interference. Oman was used as a supply post by the East India Company on route to India. Geopolitically, the country was strategically located for British forces to surround the Ottoman Empire from the south. Qaboos’ father, Sultan Said bin Taimur was trained by Britain’s India Office into a colonial mindset and ruled Oman from 1932 to 1970 as British ‘Protectorate’ – effectively a colony. The old Sultan saw Arabs as barbarians who shouldn’t be educated or have healthcare. One British adviser told him to build a hospital and he refused. ‘If I build hospital then they will want food’, he said. So there was no infrastructure in Oman.

He was very cruel. During what he described as dark times, my father migrated to Kuwait which was using its oil revenues to provide jobs and education. He learnt a lot there: Kuwait had a growing left-wing scene, with pan-Arabism, Nasserism, and trade unions. Omanis in Kuwait got involved in the movement and linked it to the situation back home, especially to Dhufar, a region of southern Oman. Dhufaris have a their own languages, culture, dress and climate. They are totally different to Omanis and other Gulf countries. They did not even have cars in Dhufar at that stage, so when they travelled abroad they realised how poor they were.

Novara: Around the end of Sultan Taimur’s reign, Britain had a Labour government led by Harold Wilson – what was its policy on Oman?

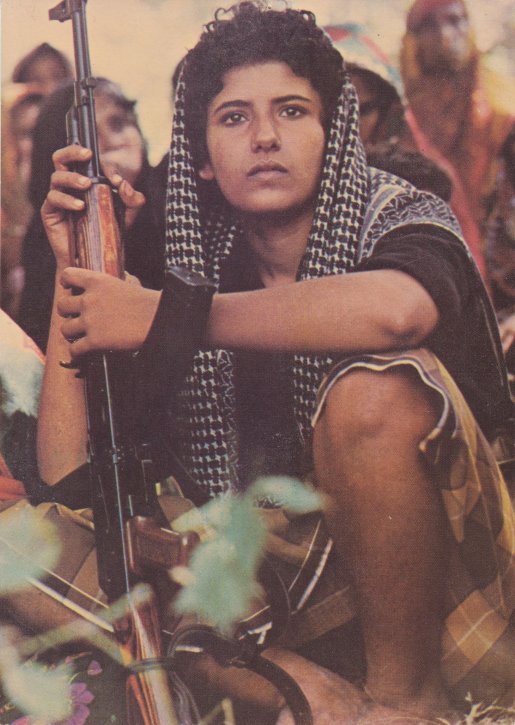

A revolution started in Dhufar in 1964. Aside from the Sultan, Oman’s powerful elite were British so it was a pan-Arabist movement for independence from the Sultan and the colonial situation. The revolution attracted 80% of Dhufaris and they started an armed struggle. They were really progressive, and also had an intellectual project and a strong focus on Women’s liberation, in terms of equal inheritance rights, ending polygamy, girls’ schools, jobs for women, which was very interesting compared to other movements in the region. Perhaps that was one reason why Britain sent one of their most elite fighting units, the SAS, to crush it. There are many photos from the revolution of Dhufari women with weapons, short hair — they were fighters too, like Kurdish women now. I met people who told me that was the only time women in Oman had that much prosperity – and it is remembered with a mixture of pride and sadness. Many fled to Yemen, or surrendered.

Wilson’s Labour government used brutal methods to keep the Sultan in power. The RAF enforced a policy of “water denial”, in other words the bombing of wells. But the Sultan was so unpopular that the revolution spread from the south to the north of Oman, inspiring movements across the Gulf and gaining support especially in Bahrain, another British colony. The tipping point was when a young revolutionary, Zaher al-Miyahi, began attacking British military bases near Oman’s capital of Muscat. Even British companies like Shell, who had oil fields in Oman, were worried. Britain was in the midst of an election, which Wilson would lose. Whitehall decided to take drastic action, overthrowing the Sultan and installing his son, Qaboos, on the throne.

Novara: Some supporters of Oman see Sultan Qaboos as a benevolent dictator who is less cruel than his father. How do you respond to that?

The new Sultan began a “hearts and minds” campaign to crush the revolution. He used oil revenues to build hospitals, schools and roads. State jobs were handed out to secure loyalty. Meanwhile, the SAS refined their counter-insurgency campaign in Dhufar against the armed resistance. The revolution was mostly crushed by 1976 – it seems Harold Wilson’s second Labour government (elected in 1974) was determined to finish the job.

There are Omanis alive today who lived through this cruelty and don’t want to rise up again. It became normal to live with terror. So the regime has retained control using fear – Omani’s cannot even say the Sultan’s name and have to call him abunah – ‘our father’. It is legally forbidden to say anything about the Dhufar Revolution. Yes, the new Sultan built schools, but pupils are taught not to question anything. They designed new human beings who can’t think, who have no intellectual curiosity – education was available but it was empty. We lived just to be loyal. We can’t think for ourselves. We don’t have political or civil rights. It hurts me to see Omanis who still live like this, without knowing anything about our past, or our future, we just live day by day, not allowed to speak out. And it makes me angry when I think that the British government designed and implemented this system for Qaboos.

Novara: What happened to Oman in the Arab Spring? Was there another challenge to Sultan Qaboos?

I was studying law part-time through a distance learning course in Egypt, with two months a year spent in Cairo for classes. I met Egyptian students engaged in protests and debates. I could feel the anger boiling, every time I visited it was hotter than before. I was there in December 2010. The Arab Spring had already started in Tunisia, and I saw the first protests in Egypt before I had to go back to Oman.

In February 2011, the Arab Spring erupted in Sohar and I joined the protests – a sit in – on the first day. I wasn’t an organiser.. It was very good experience, I felt the revolutionary spirit and it was the first time I sensed freedom. The wall of fear collapsed suddenly: we had power. We could do it. The police retreated and there were none in the city. We organised our own security. Crime dropped. Maybe there was none at all because everyone looked out for each other. We fed each other. We had democratic debates in the sit-ins about the best way to do things, even though we had no training. It was natural. I felt great.

Unfortunately in April, the Omani army moved in and attacked us brutally. I was sitting there and they hit me. A state of emergency was declared in the city and they arrested 800 people. Unofficially six people were killed, officially two. I was sent to prison – but even there it was a good experience, because we were together and continued the debate, remembering the good days and strategising what to say during the interrogations to protect each other.

Novara: What did you do after the Arab Spring?

Qaboos offered amnesty to all the political prisoners, apart from 26 really poor protestors, scapegoats he charged with terrorism. Something changed for me then. When I was released I started to write under my real name, the fear was gone. I critiqued what happened and slammed the government. Five friends and I started a campaign to release the remaining 26 prisoners. We didn’t want the revolutionary spirit to die and needed action. A gathering of nine people was illegal, but our team of six could meet.

We started Facebook accounts, writing 30-40 posts every day. I became the most prolific critic of the Sultan, his secret police and British advisers. Soon I was summoned by the public prosecutor. They warned me I couldn’t refer to the Sultan like this and had to use his full honorific title. They tried carrot and stick, even offering me a position. I refused to work for them and decided to upgrade my activities. I made plans with some guys to start a pirate radio and an opposition youth movement, we had full plans of where to buy equipment. There was only one voice, the government’s. We needed our own. Radio would be the most powerful, and distributing leaflets in mosques. We contacting unions in oil fields – which had flourished at the end of 2011 as small concession after the Arab Spring, so now every company had one, but regulated by government on where they can strike. Airport workers were forbidden from striking for example.

Novara: Have the new trade unions gone on strike and how has the Sultan reacted?

In May 2012, 10,000 oil field workers, mostly from Shell, started a strike independently of our group. The oil production stopped in Oman. The workers demanded more rights like holidays, contracts not sub contracts. 700 people were sacked. Many were arrested. At the same time, Qaboos came to London for the Queen’s 90th Birthday. He took over a hundred horses to the UK to celebrate. It was one of biggest horse transportations by air in history, costing millions – just a year after his people went out on the streets and died because they were asking for jobs. What was he doing humiliating us like this? It made me very angry.

I organised a demonstration with a friend in Muscat in the middle of the capital. We asked who’s important – horses or humans? About 100 people joined us. I also organised something to support the strikers, asking for political rights like freedom of expression and assembly, workers rights. We needed our political rights to guarantee the economic rights. This type of protest was new in Oman – small, organised, against Qaboos personally and for political rights. The Arab Spring had been about economic rights. But now we knew what we needed and upgraded the demands. Then I attended another protest organised by some others, there were at least 2,000 riot police for around 100 of us. I counted these big vans, they could take 50 police and there were 50 of them. They were demonstrating their power and shouting to try to scare us. But for me I wasn’t scared any more. They were all wearing black, masked. The protestors decided to leave to avoid a massacre. They said we have 3 minutes until we start beating you, not arresting you.

Novara: That sounds terrifying. What happened next?

A week later, on 6 June 2012, I got call at 7am asking me to attend the police special branch, like you have here – now you’ll understand that Oman is designed by the UK, our police structure is the same as your Met police. They said come and don’t worry. I thought it was just a talk and went along. They told me to sit in an office and someone will come. After 5 or 10 minutes a group of special forces wearing black with automatic rifles slammed the door and shouted at me to face the wall. They tasered me in the ribs with an electric shock baton, and put a black bag over me from head to toe. They took my glasses and phone, and cable tied my hands behind my back so tightly it left marks. My feet were in leg irons and they pepper sprayed the outside of the bag so it was hard to breath.

My father’s stories flashed through mind. Where were they taking me? Are they about to kill me? They put me inside a bare cell and untied the bag. It was so humiliating. The cell was small, 2×1.5 metres, and they were pointing their guns at me. There was a high ceiling with a very bright light, so powerful. There was no natural light. Sometimes it was bitterly cold, and sometimes it was searingly hot. There was a microphone and a speaker in the ceiling. A steel door with an opening at the bottom to deliver food and a button I could press if I wanted to go to the toilet. Of course they would take ages to come and I’d have to piss on myself. The music from the speaker was deafeningly loud – patriotic Omani songs praising the Sultan for 24 hours non-stop. I lost track of time and didn’t know morning from night.

At some point probably in the first week I tried to kill myself by hitting my head on the wall. The guards didn’t try to stop me. The first time nothing happened and I decided I needed a stronger impact. I walked back and tried to hit the wall like I was a footballer heading a ball. The impact was so strong and I collapsed. I woke up bleeding. I didn’t know if I was dead now or alive. I wondered if people who had died here had spirits inside the cells. I knocked myself out again and then the guards came and kicked me to wake me up. Then I decided maybe it was my destiny not to die now, but to fight.

Novara: It sounds like torture. I know Britain has used similar techniques itself (hooding, sensory deprivation, extreme temperatures) to break prisoners in many situations. How did you resist and survive being alone in that cell?

I made plays using the walls to occupy myself. One wall was called ‘Freedom’ and the other ‘Khalfan’. They’d speak to each other – comedies, debates, sometimes we fought. It was funny for me, this survival mechanism I developed. Later I learnt 12 of us had been arrested and charged on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the regime. After 32 days in that cell they took me to the public prosecutor in the full bag. I thought I was being taken to be executed. My mind was totally prepared for death. During the interrogations they were telling me that I deserved to die, that I was a cockroach that they needed to smash, that I was very bad for Oman for organising protests.

Eventually I was taken to court on charges of attempting to overthrow the regime and insulting the Sultan. The prosecutor and judge were sat on the same table together. I was given a lawyer who I’d never met before, and my dad managed to see me. He told me what was happening to my friends. In the end I had 14 hearings, shuttled between court and prison. In September they granted bail and I learnt I’d lost my job, was banned from working and barred from travelling.

Novara: What did you do when you were released from jail?

I restarted my activism on social media – most of the others arrested had stopped campaigning. The media were calling me a traitor who wanted to spoil Omani culture and traditions. People were scared to talk to me. My wife was worried and so were her family. I didn’t have money – before I earned a decent wage. It was so confusing. I couldn’t go back to how I was before, because now my mind was free – I could question things. I felt brave, but the impact on my family was too much. Many friends abandoned me, my political group went quiet. Not everyone could take the torture.

Then I heard Prince Charles was coming to Oman to promote two trade deals. The sale of Typhoon fighter jets worth £3bn and a huge BP gas deal where BP take 60% of revenues and Oman only got 40%. I thought the western media would travel with Prince Charles. I wanted to organise a demonstration to highlight the brutality we had suffered and protest against British involvement. I tried to publicise it on WhatsApp, and a single Facebook post, with an inspirational message encouraging people to protest.

It looks like the Internal Security Service – Oman’s MI5 – were tracking me. Two days before Prince Charles visited, I was kidnapped from my car. I was driving and two cars came up from behind like in a movie. I saw a GMC style-car in the back mirror coming so fast, and a second later they had boxed me in front and stopped me. Masked men were jumping on the bonnet, with automatic guns. Someone opened the door, another undid my seat belt, and a third lifted me like I was as light as a butterfly. I was heavy, so I laughed! I needed humour during those times. They put the long bag over me again and handcuffs and I was back in the same kind of cell. Look at how professional it was – maybe the British are involved in training them to do these special forces tactics. They released me after Prince Charles left Oman.

Novara: Its amazing that these things happen to pro-democracy activists when British Royals visit the Gulf. There was something similar in Bahrain when Prince Charles and Princess Diana visited there in the 1980s. How did all these arrests impact on your activism?

By now I had no money and no work. I was abandoned by society and followed by cars all the time. People were coming up to me in the street saying I was an ant and soon they’d come to smash me up. I felt I couldn’t take it any more and I left. Nabhan al-Hanashi, a dissident blogger, had already gone to Beirut and got UN protection. We decided to go together to the UK to claim asylum. At that time I didn’t know why, but now I think it was the imperial effect. I knew English, I only knew about Britain in my life so it felt like the only option. It’s like francophone Africans go to France. I wanted a new life, where I could contribute. I thought I was smart enough but I didn’t have opportunities in Oman, where we weren’t supposed to read or analyse.

I claimed asylum in the UK in January 2014 and the Home Office housed me in Hull. If I managed to sleep for more than three hours I was lucky. My sleep was mixed with nightmares – like I was strapped to the front of a helicopter and flown to Muscat. I was self-medicating, because it was an eight month wait for a psychologist. I realised people in UK were suffering too, dying from austerity, so I started to build an international consciousness that people suffer in the first world as well.

Novara: 2014 was a very difficult time for lots of people in the UK. What did you think of Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Labour leader in 2015?

When Jeremy Corbyn became leader of the opposition I saw the hope, for people who were desperate, dying, homeless, in poverty, unemployed graduates. He came and gave them hope that threatened the establishment. It will be very difficult for him to stick to these principles, but he has to ask if that will work and if he wants to stand with people. It’s more a question for him not for us, for him to really stick to his principles. Why are people gathering around him? Because they see something different. But why am I not? Because when I started reading about Oman’s history I saw that Harold Wilson was complicit in Oman’s oppression and wondered if Jeremy Corbyn will change this situation or not.

In March 2016, I was staying with a friend in Wales while I was an asylum seeker, and she took me to a Labour party event in the Valleys. Jeremy Corbyn was there and speaking to everyone. My friend dragged me over to him and I told him I was an asylum seeker from Oman. The first thing he asked me, which was nice of him, was if I felt safe here. I said compared to Oman yes, but I have questions about UK involvement in Oman – and he told me he’s looking at that closely. What I got from him was he wanted to know more about what was happening there – that the establishment is trying to keep him away from it.

Novara: … and John McDonnell?

When I moved to London, after winning my asylum case, I enrolled in college here and went to protests every fortnight for the NHS and different left-wing causes. After one Save the NHS demonstration an Irish friend took me to a pub in Whitehall. Suddenly we saw John McDonnell in there and he walked passed me. I stopped him and shook his hand and said “Hello! My name is Khalfan and I’m from Oman. Do you know where Oman is?” I think he was surprised by this way of greeting! He said Jeremy and him were looking very closely to try to find out more about what was happening there, but again my impression was he didn’t know much.

Novara: If Jeremy Corbyn became Prime Minister, what do you want him to do about UK policy towards Oman?

The first thing for Omanis, if Jeremy Corbyn succeeded in getting into Downing Street, is we want to know what Britain is doing in Oman, we want to know the truth. Then we can make our demands. But right now there are so many British personnel in Oman, like the new Navy base at Duqm, and we don’t know what they are doing there. We say our country is the back garden of MI6. A lot of British documents have been classified for a long time and we cannot get access to them. I want to know who trained the Omanis in these torture techniques. And I want to know what the British are doing there now, why BP, Shell and the Royal family are always visiting.

Jeremy Corbyn should support democratic transition in Oman and call for that. To stand with the people and his principles. His foreign policies would also help the environment and peace. It’s illegal for more than 9 people to gather in Oman, and if it is a political meeting they will be attacked and arrested. The most important thing is for Omani people to be allowed to meet and debate, without fear of being punished like me.

To find out more about Oman, follow Khalfan on Twitter at @Omanfreedom090.