Although Claudia Jones was born in colonial Trinidad in February 1915, her formative years were spent in New York, where she moved aged 9. Immersed in the culture of Harlem, in a family and home environment wracked by poverty and the death of her mother when she was only 12 years old, Jones became a political radical at an early age. She joined the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) as a young woman, primarily because of the role played by that organisation in taking the lead in the fight against the racist arrest and conviction of the so-called Scottsboro Boys – a group of young black men – on trumped-up charges, only recently rescinded, of attacking and raping white women on a train en route to Memphis. By 1937, Jones was on the editorial staff of the Daily Worker. During the Second World War, she edited Spotlight, the magazine of the Communist-affiliated American Youth for Democracy. Consequently, she was arrested and sent to Ellis Island, New York in 1948 on account of her Communist activities. In the 1950s, she was served with the deportation order that led to her moving to London in 1955.

What did she do?

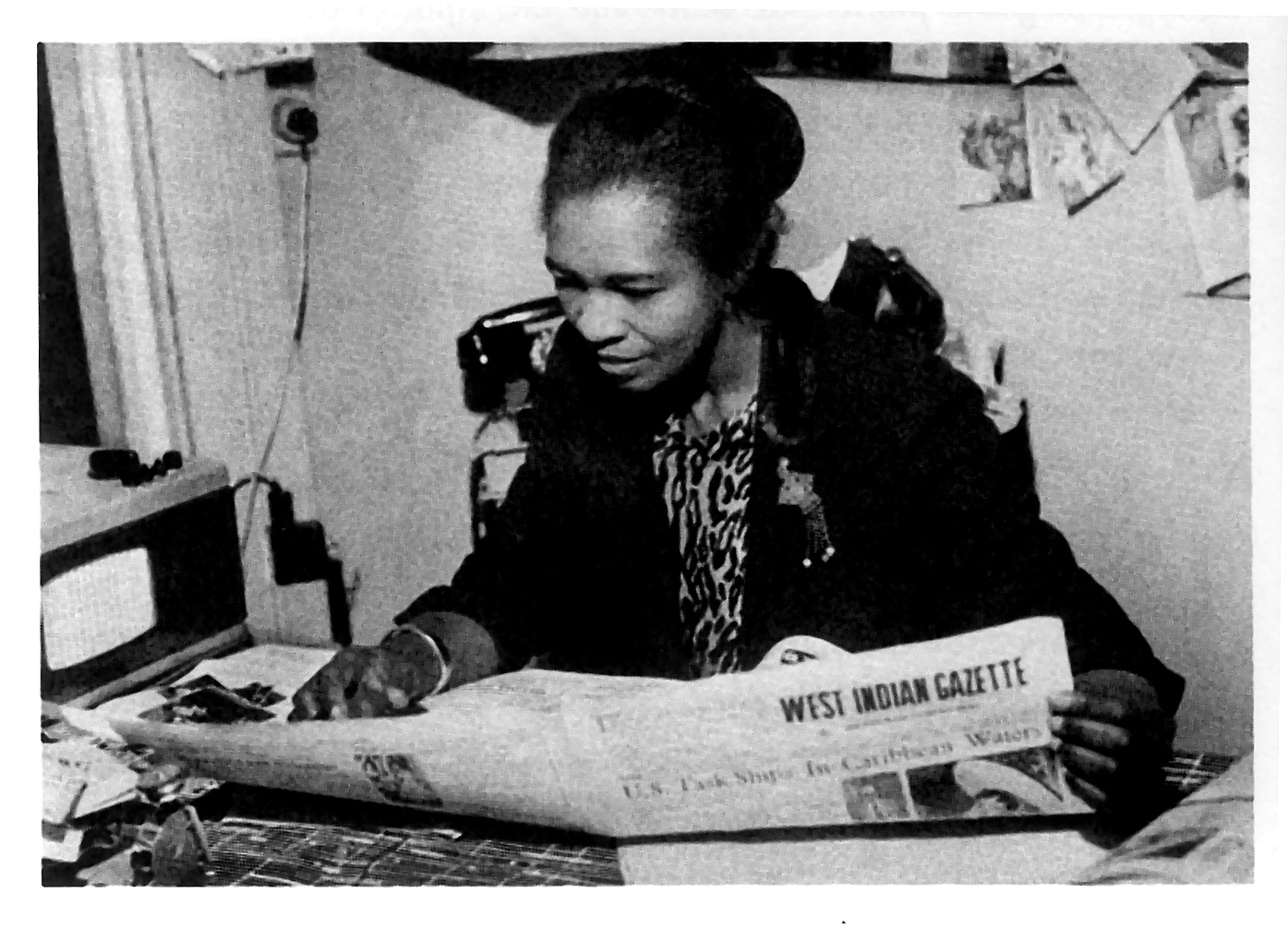

Prior to her deportation, Jones was given a rousing send-off by the CPUSA. Yet her arrival in Britain went without similar acknowledgement from the domestic Communist apparatus. However, this didn’t hold Jones back from launching herself into a world of radical anti-racist, feminist and anti-colonial activism in the UK. Central to her achievements were two substantial projects, the legacies of which remain with us today. Firstly, in 1958, barely four months before racist rioting broke out in Liverpool and Nottingham directed against immigrant communities, Jones launched the West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News. Such an initiative, launched into the generally hostile national climate of the time, played a major role in opening a space in the public sphere for black activists and writers, and served as a primary conduit for ideas and events centred on the non-European world to be transmitted into the imperial metropolis. Appearing monthly, the paper covered events from Africa, Asia and, primarily, the Caribbean, with a specific attention given to struggles against empire. Unsurprisingly, the paper saw the Cuban Revolution as a decisive event in Caribbean and world history, publishing pieces by Eric Hobsbawm and Walter Rodney, amongst others. The Gazette has been described by Bill Schwarz as “the house-paper for a generation of Caribbean intellectuals who had made the journey to London”. From 1963, Jones made Africa Unity House in London her political base while she worked to establish a coalition of African and Asian diasporic political organisations in Britain to spearhead struggles against racism and empire. Secondly, Jones was a (perhaps the) central figure in the founding of the Notting Hill Carnival. Despite opposition from Communist comrades who viewed such things as carnivals as little more than trivial side-shows, Jones and others involved with the West Indian Gazette pushed ahead with the idea of a carnival in London timed to coincide with carnival season in Trinidad. The Gazette was used to advertise and organise the Carnival, and Jones saw the two projects as closely linked. Out of the white rioting of 1958, and ahead of imminent anti-immigrant legislation and the 1959 murder of Kelso Cochrane, the accomplishment of holding the inaugural Carnival in St Pancras Town Hall in 1959 was monumental. That Jones herself saw carnivals as directly political acts is evident from the title of her piece included in the souvenir programme of the first Carnival: ‘A people’s art is the genesis of their freedom’.

What were her ideas?

Jones was driven by activism; she was no idle academic theoretician, but instead drew her conceptualisations of the world from her direct experiences of political activity. In this regard, Jones drew together two central theoretical principles that remain relevant today. First, the principles of Marxism are only of use insomuch as they relate to the material experiences of those at the brunt end of capitalist exploitation. As Jones herself put it in her submissions to court prior to deportation from the USA: “It was out of my Jim Crow experiences as a young Negro woman, experiences likewise born of working-class poverty that led me in my search of why these things had to be that led me to … the philosophy of my life, the science of Marxism-Leninism.” To this end, Jones centred much of her writing around questions of anti-racism and feminism. As she wrote in Political Affairs in 1951, “the economic, political and social demands of Negro women are not just ordinary demands, but special demands, flowing from special discrimination facing Negro women as women, as workers, and as Negroes.” Second, Jones stands out as a foremost figure in the attempt to transmit a tricontinental, internationalist radical politics into the heart of Britain. Recall that Jones’s launching of the Afro–Asian Caribbean News – its very title an invocation of tricontinentalism – came more than a decade before Che Guevera’s more celebrated ‘Message to the Tricontinental’. That Jones was articulating such a vision from within a country wracked by racist violence, rather than Guevara’s revolutionary Caribbean island, speaks to the tenacity of Jones’s activism, and her channelling of the Bandung spirit of Afro-Asian solidarity against racism and imperialism.

What is her legacy?

Carol Boyce-Davies, Jones’s biographer, suggests that in London both her ideas and her political activism took on an increasingly pan-Africanist character. Largely this was due to hostility from British Communists, whose reluctance to embrace a black colonial woman as a leading activist in her own right saw her take only a minor role in Party activities. Whilst the Notting Hill Carnival has become something of a society day-out – anyone recall William Hague and his wife in attendance, khaki outfit and all? – its place in the history of anti-racist struggle, and that of Claudia Jones and her colleagues in its founding, is a major legacy. To the limited extent that Britain has become a post-imperial society, Jones and the activists with whom she worked deserve much of the credit, in particular for their efforts at the heart of non-white communities resisting racist violence. Jones’s brand of anti-racist feminism, inspired by Marxism but operative most clearly in autonomous political initiatives such as the West Indian Gazette, is needed now more than ever. In 1960, Oswald Mosely rallied in Brixton and called for all ‘Jamaicans’ to be sent home; the Gazette denounced Mosely, receiving threats for their troubles and seeing their offices ransacked and vandalised in 1961. An era of Powellite racism from political and media elites walked hand-in-hand with racist violence on the streets. The parallels with today do not require spelling out.