Have you heard about the 8-month old radical left party that recently topped the Spanish polls? If you have, that may well be the extent of the information that has made it to you across the Bay of Biscay.

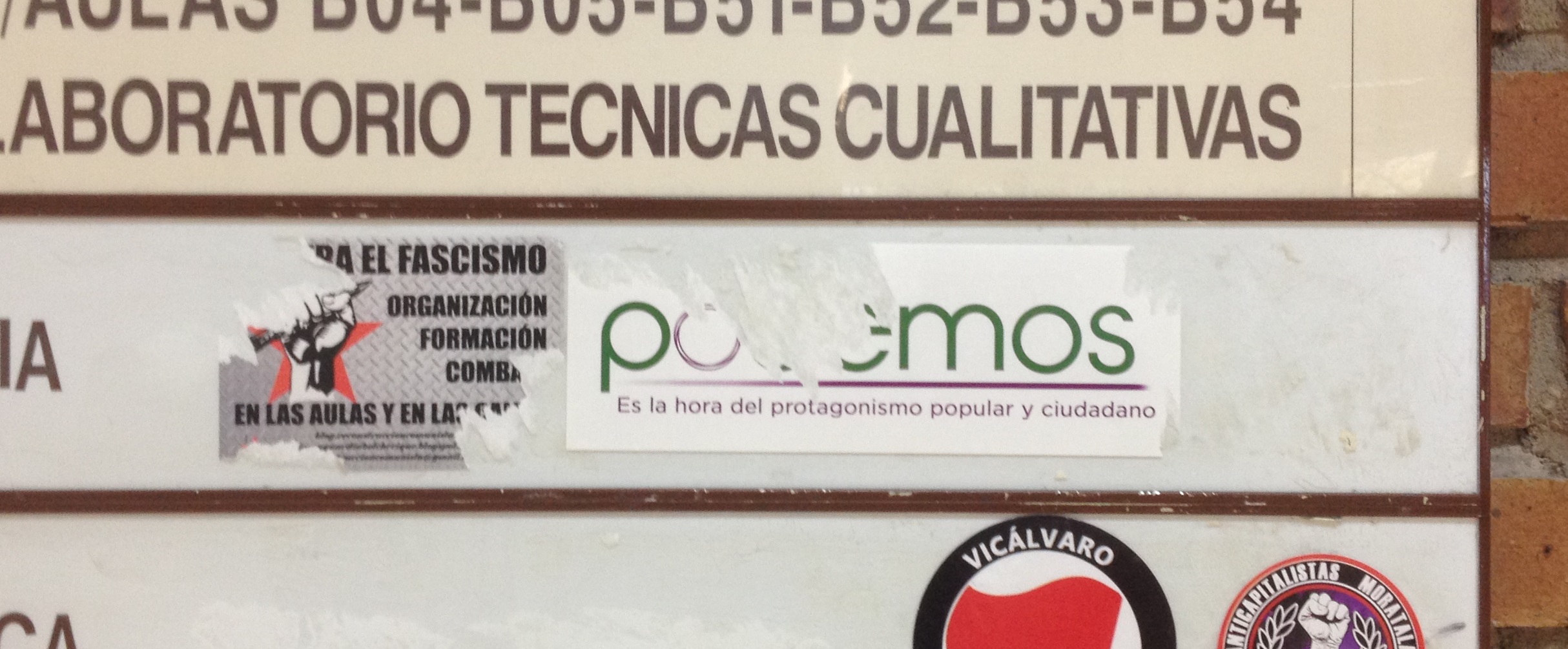

Podemos (‘We can’) was founded in January 2014 with pretensions of breaking the two-party hegemony in Spanish politics. The political backdrop is fairly familiar: Spanish electoral politics is dominated by sold-out socialists (PSOE) and a supposedly centre-right party (People’s Party) that has one too many historic links to Franco’s dictatorship. These parties have together been dubbed the ‘PPSOE’ by Spain’s post-crisis social movements.

1. There is an indignant backdrop.

Until last year Spain’s electoral politics were a long way from the renewed vibrancy of its street politics. Since the occupation of Madrid’s Puerta del Sol on 15 May 2011, a rejuvenated civil society has built new grassroots political institutions to respond to the economic crisis that still devastates Spain.

The squares movement spread to the formation of neighbourhood assemblies and is now strongest in localised responses to material threats such as evictions, school closures and healthcare privatisation. Although 15-M’s use of the ‘#spanishrevolution’ hashtag proved premature, the change in public political consciousness in Spain in the last four years cannot be overstated. There are very few in Spain who have not been materially affected by the crisis, be it through the quadrupling of university tuition fees, the shafting of those with savings in major banks, or thousands of evictions. There are thus very few who don’t sympathise with the very broad demographic taking to the streets.

2. It could have been X.

In January 2013 the Partido X (‘X Party’) rose from hacker communities involved in 15-M’s occupations and assemblies. It summarised its programme as democracia y punto (‘democracy full stop’), its platform being the installation of a directly democratic, somewhat technocratic, ‘wikigovernment’. A rigorously democratic party organisation was a priority and Partido X did all it could to avoid personality politics, including remaining an anonymous group for nearly a year.

How did this well-prepared, supposedly hyperdemocratic party do in the May 2014 European elections? It received just over 100,000 votes. How about Podemos, a four-month old party with claims to be democratic but with little formalised internal organisation? 1.25 million votes.

It is clear that there is more to the Podemos story than timing and a leftist, democratic platform. What was it that made Podemos different?

3. Pablemos?

The story of Podemos’s success is inseparable from the story of Pablo Iglesias’s increasing prominence in the Spanish media.

Iglesias is the party’s figurehead, if not formally the leader. Formerly a professor of Political Science at the Complutense University of Madrid, Iglesias started out blogging for a smaller national newspaper before being offered his own TV shows (La Tuerka and Fort Apache).

Although not prime-time successes, they picked up a cult following and crucially created an independent space for Iglesias to develop his own media profile and narrative. From his position as host of these programmes, Iglesias became an increasingly common prime-time commentator. The latest peak in his media profile was an hour-long interview by one of Spain’s most renowned political journalists, Jordi Évole, which was La Sexta’s most watched non-sport broadcast to date (5 million viewers).

4. Podemos is using a Bolivarian strategy.

Podemos’s foundation was a strategic seizing of the political opportunity of Iglesias’ growing media profile. In an interview with La Marea, Luis Alegre, one of Podemos’s co-founders, describes how the project required a “charismatic figure” and that it took a couple of months to convince Pablo Iglesias to take up this role. In the European elections Podemos even used Iglesias’s face to represent the party on the ballot papers. They justified this by claiming that more than 50% of Spanish voters recognised Iglesias’s face whereas only around 10% recognised Podemos by name.

The party’s strategy is directly influenced by Latin America’s resurgent Bolivarian left whose charismatic figureheads have been central to electoral success. Co-founder Juan Carlos Monedero worked as an advisor to Hugo Chavez, and the party’s European election campaign manager, Íñigo Errejón, advised Evo Morales’s Bolivian government and Rafael Correa’s Ecuadorian government. Podemos’s ‘circles’ – neighbourhood level assemblies that form the party’s grassroots – even use the same term as those formed in Venezuela under Hugo Chavez.

5. A new vocabulary for a new politics.

Podemos is Bolivarian in strategy but not in imagery or language. It eschews all traditional partisan imagery, using purple as its main colour and presenting no demands or policies on the front page of its website. Instead the options all emphasis the party’s democratic nature: ‘vote’, ‘participate’ and ‘citizens’ assembly’.

Pablo Iglesias and Podemos have created a parallel political vocabulary that allows its overall narrative to resonate with Spain’s social movements while avoiding language that might alienate those disenchanted by the left. It positions itself as party of ‘people’ (gente) but not ‘the people’ (el pueblo). It does not attack capitalism or capitalists but rather takes aim at la casta (roughly ‘the elite’: a term that Spanish commentators have compared to the Occupy movement’s use of ‘the 1%’).

The party’s name is the strongest example of this: ‘Podemos’ (We can) carefully matches the sentiment of the ¡sí se puede! (roughly ‘yes it is possible’) refrain often heard at Spanish protests without appropriating the term.

6. We can! But what exactly?

Podemos’s platform is now fairly detailed, comprising 36 pages of policy on a wide variety of themes. This collaboratively written document is accompanied by higher-profile policies spearheaded by individuals in the party, such as the anti-corruption measures proposed at the European Parliament by ex-Podemos MEP and former anti-corruption public prosecutor Carlos Jímenez Villarejo.

The content of Podemos’s platform will be familiar to those who follow the Greens in England, Wales and Scotland. Renationalisation of oligopolies, tighter corporate regulation, expansionary economic policy, opposition to TTIP, support for small and medium size enterprises and a universal basic income are prominent in Pablo Iglesias’s rhetoric.

Podemos may not be calling for the abolition of private property, but it is proposing strong transitional measures that could make more radical action increasingly possible. The universal basic income is a particular focus for Iglesias, who manages to advocate an unfamiliar and radical policy clearly and powerfully to prime-time audiences.

7. The emergent internal democracy is fragile.

Podemos’s electoral success has been somewhat more rapid than the development of their internal party structure. For now a sort of soapbox democracy is at play: Pablo Iglesias’s reputation as a public figure is so new and fragile that he has to stay true to popular sentiment or risk a collapse in support.

It remains unclear exactly what will keep the party’s leadership true to the radicalism of the grassroots once elected. Building this robust internal democracy is a preoccupation of many local Podemos circles whose attention is now divided between building local participation and technical discussions of internal procedures.

8. ¿Y nosotros Podemos también?

Should the UK left be looking to repeat the Podemos story?

Firstly, the context is very different: the Occupy movement didn’t reach as many town squares as 15-M and it never sparked consistent neighbourhood level organising. The dominant popular political narrative is sadly not as far as it ought to be from the xenophobic, conservative, victim-blaming rhetoric of the LabLibCons (not quite as neat a term as PPSOE). A Podemos-style meteoric rise would require groundwork.

Secondly, we already have a party with a very similar platform to Podemos whose support is surging. The Greens have several advantages over Podemos such as a well developed internal democracy and a relatively friendly relationship with social movements. Among housing and education activists I have spoken to in Spain, Podemos is begrudgingly accepted and passively supported. There appears little dialogue and even less enthusiasm.

At a recent education demonstration during a three-day student strike, a chant of “Where is Pablo Iglesias?” started by the anarchist Iberian Federation for Libertarian Youth was well received and echoed. This distance from social movements allows Podemos to project an image that is more easily accepted by armchair indignados but may well limit its ability to stay true to its grassroots.