It is often stated that an overall decline in voter turnout at national elections – especially of marginalised groups in society – is a problem for democratic legitimacy, which relies on political participation. Here Raph Schlembach points out that such legitimacy is also bound up with citizenship rights and with the exclusion of non-citizens.

1. The personal is political.

I am not a British citizen, so my personal circumstances mean that I am not allowed to vote in the general election for the 56th Parliament of the United Kingdom. Neither are those under 18 years of age, the citizens of non-Commonwealth countries, prisoners and those in ‘secure hospitals’, those with irregular or no documentation, and members of the House of Lords.

2. Parliament cannot represent all of us.

This means that you, the British electorate, can effectively decide ‘on behalf’ of those of us ineligible to vote. Those left unrepresented by parliament are also the Afghanis and Iraqis affected by your defence policy, the Syrians and Eritreans affected by your asylum policy, the non-EU citizens affected by your immigration policy, all those around the world affected by your economic and environmental policies… and so on.

3. General elections divide us into citizens and non-citizens.

There is a good reason to list the categories of people who are not allowed to vote. It makes us understand that general elections are not about having a voice: they are about something else.

They turn people into legal personae with abstract rights and responsibilities, including the right to vote. You become a citizen – a subject of the state. Citizens make representative democracy possible, giving the national state’s parliament the legitimate and democratic right to pass legislation and to form a government. In short, national elections are about state sovereignty.

Now, representative democracy is surely not the worst form of sovereignty. I certainly prefer it to the sovereignty of rulers and leaders that was bestowed by god, by title or by property. But the traditions of the liberal state are based upon a logic of exclusion – they don’t always apply to the non-citizen, or to those who had some of their citizen’s rights revoked.

4. Representative democracy is paradoxical.

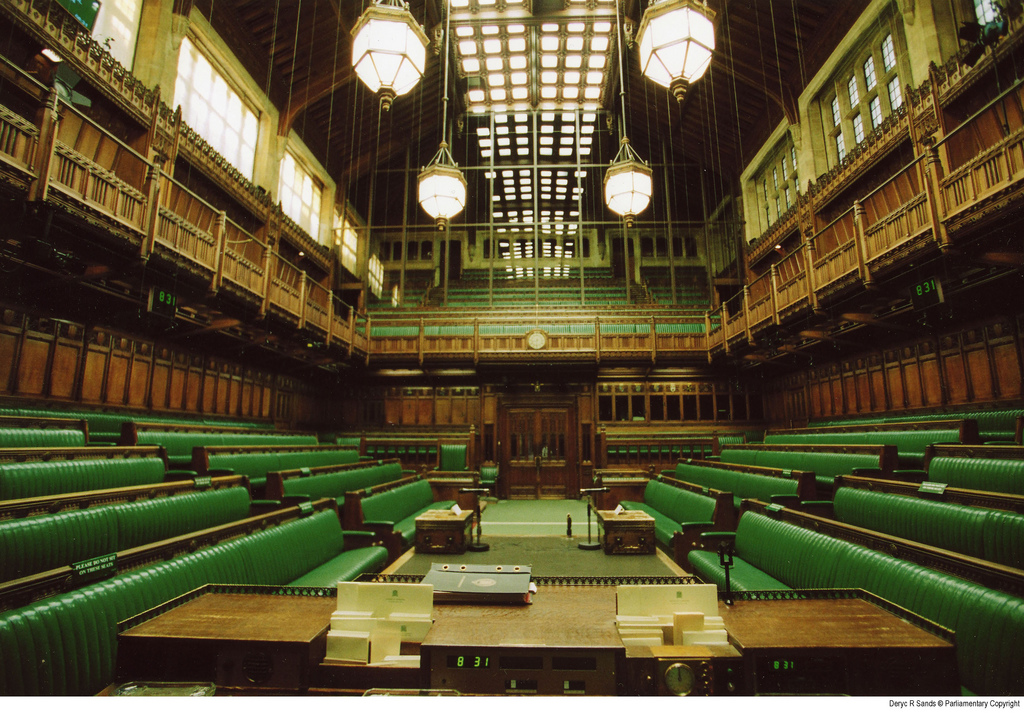

By offering your vote once every five years to a political party that will represent you in the House of Commons you affirm the legitimacy and authority of the state over your person. The paradox of citizenship is that it grants you the best possible protection from the use and abuse of power and at the same time it legitimises those very same existing power relations.

Governing always means seeing human beings as citizens. It means separating the personal from the political. For a state, and for any political party that seeks to be elected to form the government of a state, political rights are always granted through inclusion into the system of citizenship, not through recognition of personal ability or need.

5. Because the refusal of citizenship is an impossibility…

…we should give it a go. Does that mean refusing to vote in the general election? Maybe. Party politics presents itself to us as the only option: ‘there is no alternative’ – refusing our rights as a citizen of the state would be to our detriment.

There are of course the moral arguments against elections: all politicians are Janus-faced liars, corrupt, greedy, power-hungry and in the pockets of corporations. I don’t think that is true. There are the purist arguments against elections: all elections are wrong; we need direct democracy. That argument misses the fact that there is certainly a difference whether you vote in a national election or in the AGM of your sports club.

A more critical argument against elections would not question voting as a method, but the setting in which it takes place; in this case the liberal-democratic state. It is about questioning the space where politics is supposed to take place and about expanding the realm of political action.