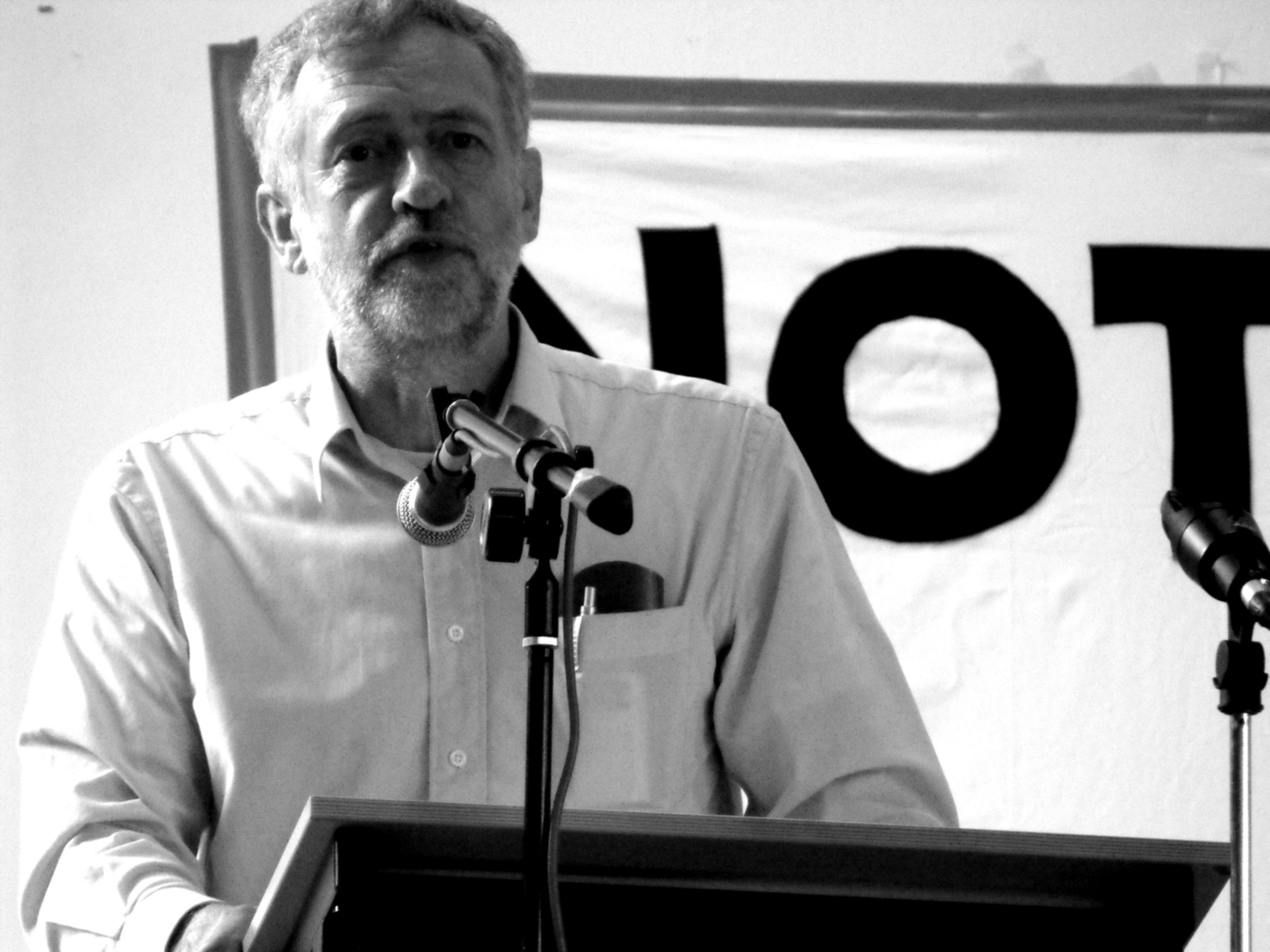

This week, the Labour leadership contender Jeremy Corbyn sat down for an interview with NovaraTV. Watch it above, or on the Novara Media Facebook page. You can read Aaron Bastani’s thoughts from it here on NovaraWire. What follows are five responses to potential stumbling blocks in Corbyn’s politics.

1. Social democracy has a money problem.

Aaron’s final point is the most difficult, and is a question that has resonances across Europe at the moment. That is, how can you fund the classical model of strong-welfare states without either: a) the domestic growth and explosion in international trade characteristic of post-WW2 Europe, or b) a hugely crisis-prone finance industry undergirding your state revenue?

In Europe specifically, this is also a political question, because the way the EU and its institutions are arranged make it difficult to pull this off, both in terms of capital flight and the unremitting hostility of its high functionaries to left programmes – but even without an EU, it’s not clear there’s any simple answer to this question for ‘mature’ capitalist economies. This is the difficulty faced by social democrats in Europe at the moment. (For more on the question of Europe, listen to this week’s NovaraFM.)

2. Corbyn vs. the dead centre.

Corbyn would have been considered quite a middle-of-the-road left Labourite a few decades ago. That he is not now is a testimony to the incredible constriction of political views – and at times the total absence of political polarisation – in electoral politics in this country.

No wonder, then, he appears like the daystar of liberty for those who’ve had their head in the filth for so long. Though plainer and more direct than his competitors, he nonetheless gives the occasional politician’s answer (one may want to close a detention centre without actually committing to do so). That is his job. But there is a more general question about the transformation of political institutions here, that we get hints of in his answers on how a Labour party under him might govern: a reluctance to move away from the traditional form of politics, a certain conservatism of form that leaves unattacked broader questions about how we might organise our lives. That is, Corbyn wants more participation in democratic institutions, with which it is hard to disagree, but is less forthcoming on what the issues beyond simple participation might be.

It’s doubtless true that his emergence in the leadership race has attracted supporters who have previously felt ‘homeless’, or of wandering political sympathies, precisely because of his difference from the candidates of the dead centre; yet his solution to many of the political ills of the period remains a nebulous ‘democratisation’ without a sense of what the limits to that process might be presented by the institutions themselves. It would be useful to press him on what a ‘constitutional convention’ here would entail.

3. The state is still a stumbling block.

This is the reason for his weakness over stop-and-search and policing: his answer to it is simply ‘more training’, which leaves untackled the problem of state institutions in general, and what they might be for. This needn’t be so: it would be possible to take a left social-democratic position that says, for instance, the police are a concentration of functions, some of which should be abolished, some of which should be separated into distinct organisations and functions, being at the moment a kind of ‘armed social work’ that does nothing for the actual problems to hand.

This tends to be a frequent weakness in Labour-affiliated thinking about the state, which assumes the organs of the state are simply responsive to political control and merely need better masters, if indeed the state is ever thought about critically at all. Corbyn is well aware of the dangers of some Labour leftists’ nostalgia for centralised, dirigiste institutions, yet retains certain of its habits of thought.

4. Labour councils are still a problem.

Labour still has a local problem: that Labour councils are generally dens of corruption and venality, or agents of gatekeeping and social cleansing – especially (but not only) in London. You can answer this (and Corbyn perhaps might) by saying Department for Communities and Local Government cuts – of unbelievable severity – force councils into difficult situations in which there are no winners (adult social care, already hanging by a thread, is in serious danger under this government.)

By reversing such cuts, one might claim, councils will be relieved of their worst aspect. But is this true? Does it even begin to address the question? How councils behave, not just in the political conduct of office holders, but in the treatment of their constituents, is a litmus test of progressive government: this is especially true because for most people in need and worst hit by austerity, whose first point of contact isn’t national government but council-run services.

Why do Labour councils behave as they do, above and beyond ‘difficult decisions’, with councillors merrily hopping on the gravy train to handsomely rewarded non-executive board positions in property development after a term spent ‘regenerating’ an area? Is it not also true that state institutions themselves have an overbearing, almost irresistible, logic that is hard to resist and independent of the holder of office? How does one deal with that? And – though wanting to avoid Kremlinology – how would a Corbyn-led Labour party relate to local government bodies headed by people like Southwark’s dire Peter John?

5. What do we talk about when we talk about the Labour Party?

It is probably useless to talk (as some anarchists do) as if the Labour party were a metaphysically and unalterably bad organisation, members of which necessarily support, by joining, war, murder, deportation, exploitation, etc. And yet it is true: this is a party that has not only done these things, but continues to support them even in opposition, and whose grandees are even now taking to the broadsheet columns to explain why these things are virtues, and electoral boons.

I say it is probably useless because it is an unconvincing argument to anyone not already convinced, in part because of its reliance on a strangely a priori construction, and especially because it does not feel true to people who are members of the Labour party. These are people who have for years felt at odds with their own leadership, or who have felt themselves in struggle against their own party in power, and who very probably have asked themselves, many times: am I in the right party? The right organisation? The answers people find to those questions, either about formal links between historical working class institutions, or about the utter uselessness or impossibility of other political formulations outside it, or even simple despair at action outside of what they know to be insufficient, are better pointers to what we should be doing and arguing than making arch comments about the stupidity or moral standing of those who are part of Labour.

The better argument to be made is in terms of political choice. That is, accepting the Labour party is a large political terrain in which a struggle exists between a leftish grassroots and a party nomenklatura or caste of leaders, officials and so on, and therefore can (within certain parameters) be made to be different, can the effort such a transformation takes be justified? Does it have intrinsic limits? And in a pure question of bodies, time and urgency, does changing focus from direct work in, say, housing or workplace organisation, in care work, or fighting the gaps that state shrinkage is leaving, to getting Corbyn elected leader (as stage one of a much longer plan) seem like the best political use of one’s time?

There may well be a possible argument from despair here: nothing else is working, and to pay £3 and take your vote is not in itself a great commitment – this would be a good argument to hear made well. As would a clearer exposition of the projected relationship between a Corbyn-led party and the social movements outside it, and, necessarily, sometimes against it and holding it to account. While I do not take a purely reductionist approach which says a theory of political action is useless, or action in that sphere harmful, I’m not convinced of it here.