Tears of Oil: The Case of Ashraf Fayadh, Condemned to Death in Saudi Arabia

by Ben Morris

6 January 2016

According to Human Rights Watch, Saudi Arabia executed 155 people in 2015.

The country’s execution on Saturday of 47 more, a gross number which included the prominent Shia cleric Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, was met with predictable fury from arch-adversary Iran, and incensed protesters in countries with significant Shia populations, even drawing concerted condemnation from Western governments. In a time of upheaval in the region and wars in Syria and Yemen, the move was patently designed to stoke sectarian sentiment within the Sunni majority population to foment support for the monarchy’s military involvements.

Saudi Arabia has many problems. Aside from the insidious exportation of a radicalized religious creed and the swiftness with which the impossibly affluent royal family seeks to quell domestic and foreign opposition, perhaps the country’s most depraved characteristic is the repressive barbarism implemented by a justice system based on dogmatic extremism, the result of which the world witnessed on Saturday.

Nevertheless, despite justifiable indignation at the provocative killing of a sectarian opponent, the ire of progressive secularists would perhaps serve more purpose being channelled toward the Saudi government’s treatment of a free speech proponent who, it can reasonably be inferred, would expunge religious authoritarianism absolutely given half a chance.

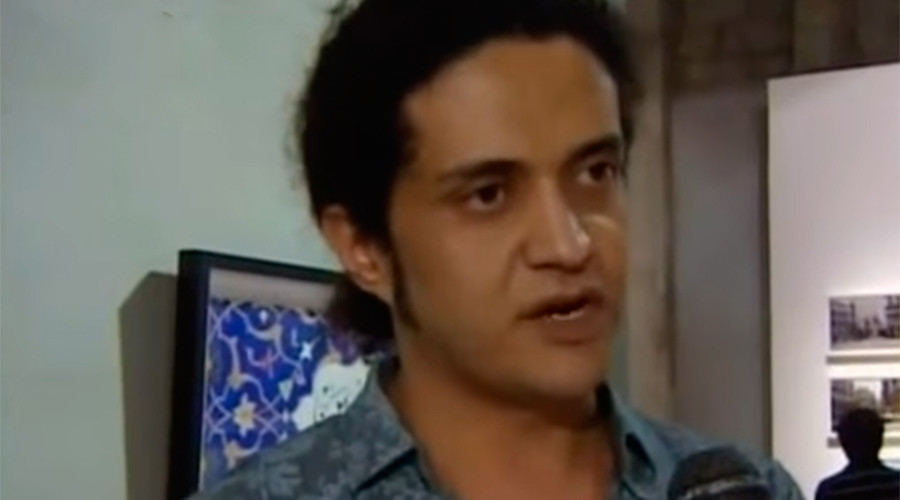

Palestinian-raised poet Ashraf Fayadh, a leading member of the nascent Saudi Arabian arts scene which has been cautiously pushing the kingdom’s boundaries of acceptability, has been sentenced to death for apostasy. This case, however, has gone somewhat under the radar.

Fayadh was originally detained in August 2013 by the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice – part of the Saudi religious police or Mutaween – following a complaint from a man, Shaheen bin Ali Abut Mismar (who is alleged to have had a previous dispute with Fayadh). Mismar stated that Fayadh had publicly cursed both the prophet Mohammed and the Saudi state, and had distributed his poem collection Instructions Within, which contains allusions to atheistic ideas.

The two arresting officers also contended that they had found photographs on Fayadh’s phone of several women, which they claim prove his involvement in illicit relationships. The accused maintains that the charges of blasphemy are complete fabrications and prove nothing illegitimate; according to Chris Dercon, Tate Modern director and friend of the poet, the images discovered on Fayadh’s phone are merely photos of fellow artists involved in an exhibition he had co-curated in Jeddah prior to his detention.

Fayadh was initially tried by a court in Abha, a city about 400 miles from Mecca, which in May 2014 sentenced him to four years in prison and 800 lashes. From this point until November 2015, he was incarcerated, denied the right to assign a lawyer and his right to appeal was consistently rejected, until he was finally retried, and on 17 November sentenced to death. The conviction, which contains a litany of obscurely-named blasphemy-related charges including ‘denying the day of resurrection’ and ‘objecting to fate and divine decree’, comes despite witnesses for the defence stating that Mismar was lying, an accusation also shared by the Mismar’s own uncle.

Fayadh has at last gained access to a lawyer, Abdulrahman al-Lahem, who has lodged an appeal against the conviction, arguing the court which handed him the sentence did not provide him a fair trial and ignored historical evidence of Fayadh’s mental illness. Al-Lahem appears buoyant, telling The Guardian: “We are confident the trial will be reversed and Fayadh will be freed based on the [legal] precedents in the kingdom.”

In addition to his honorary membership of the German division of PEN International, a worldwide association of writers who seek to defend freedom of expression, Fayadh is also part of Edge of Arabia, a British-Saudi artistic collaboration that is now “an internationally recognized platform for dialogue and exchange between the Middle East and the western world.”

The mass availability of information and easy anonymity of the digital age clearly has dire implications for the state’s capacity both to enforce laws which trespass on individual liberties, and to curtail the internet-based democratic forces that this new era is facilitating. This ever-widening disparity between the state’s ability to repress and the people’s ability to subvert has never been more evident than in the Saudi justice ministry’s recent threat to sue the Twitter user who likened the judgement brought on Fayadh to an ‘Isis-like’ act.

Yet whilst nobody can argue that democratization is an unbending and unalterable eventuality, much of the world is still enveloped in totalitarianism. What happens until the breaking-point? In a place where one cannot criticize, protest or mock, the role of the artist is transmogrified into something more indefinably nuanced. “How can we paint butterflies and scenes of the past when our region is in turmoil and change is upon us?” Edge of Arabia’s website asks.

As the collective’s manifesto states: “Once status for the artist is gained, the opinions and discussions that art ignites can receive the serious considerations they deserve, and an ‘ecosystem’ for cultural influence on society can be realised… Edge of Arabia presents a fragile but brave community of artists, as a mirror, to an increasingly excited audience, so as they might see themselves from another perspective, from another angle.”

Fayadh is a part of that brave mirror; an artist who sought to tell Saudi society about themselves from a perspective prohibited by absolutism. His case is another fracture in the widening crevice from which a tangible freedom will soon explode. He is not steeped in sectarianism but motivated by liberation from intransigent control supported by archaic doctrine. Art is fundamentally at odds with tyranny. Fayadh must not be martyred but live to see the fruits of his generation’s courage.

your mute blood will not speak up

as long as you pride yourself in death

as long as you keep announcing -secretly- that you have put your soul

at the hands of those who do not know much..

losing your soul will cost time,

much longer than what it takes to calm

your eyes that have cried tears of oil

(Ashraf Fayadh, Instructions Within. Translated by Mona Kareem. Banned from distribution in Saudi Arabia.)

Help to free Ashraf Fayadh by signing the Amnesty petition or attending an English PEN event.

Photo: Ashraf Fayadh/YouTube

–

If you want to support media for a different politics, you can donate or subscribe to Novara Media at support.novaramedia.com.