So 44% of the public think the British empire is something to be proud of. And almost half of them (49%) think it was a good thing even for the countries that were colonised by it. These figures have shocked and appalled commentators on the left, including Novara’s own Aaron Bastani. But beyond justified outrage, we need to understand why ideas like this remain so rife – so we can build a strategy to change them.

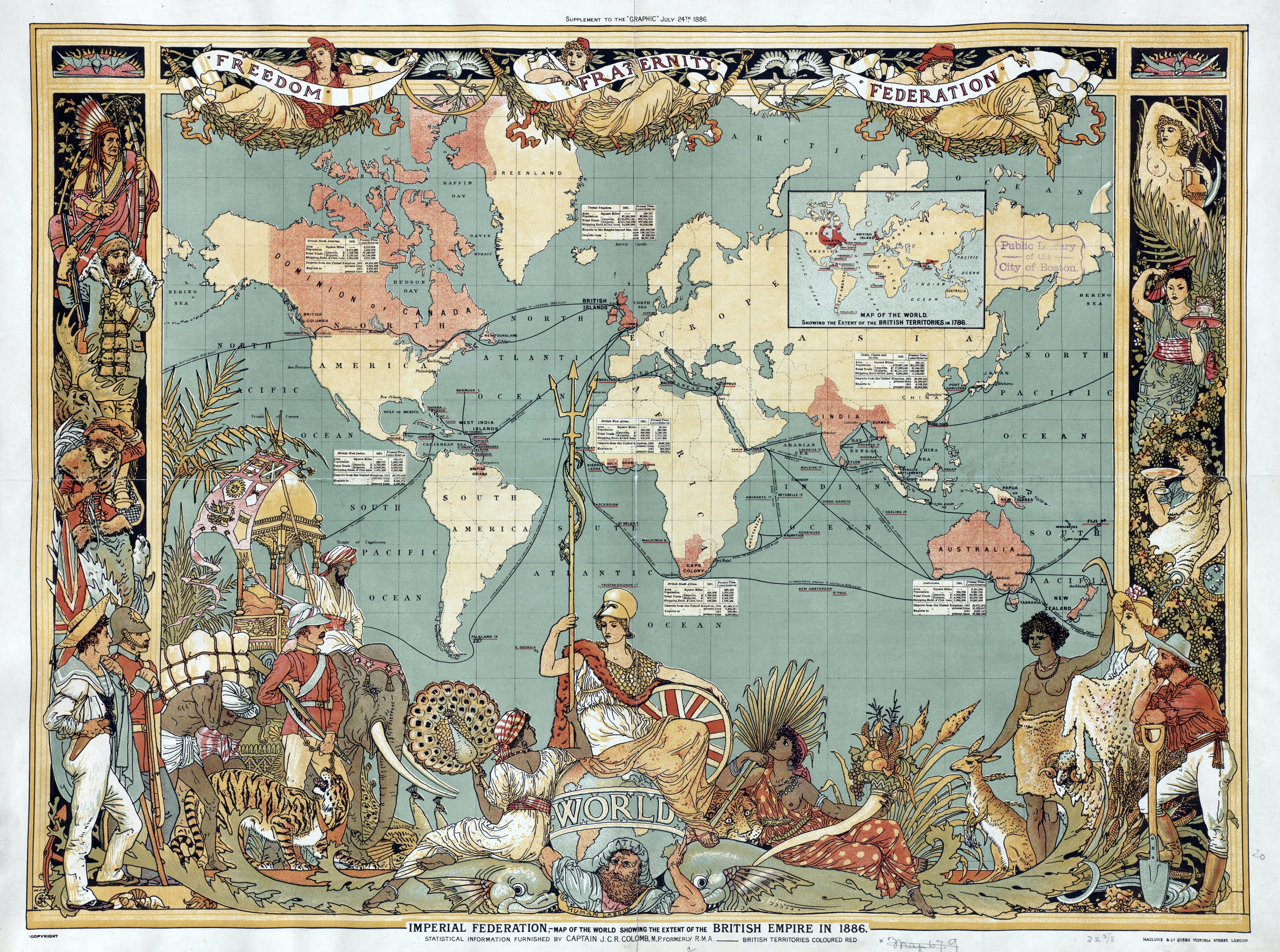

When people believe the British empire was a noble institution which brought civilisation to distant ‘savages’, when they buy into the Victorian mythology of the ‘white man’s burden‘, that belief helps prop up a larger network of white-supremacist views, including ideas about immigration, multiculturalism and policing. At the same time, a historical framework that justifies brutal exploitation on a global level is also one that suits the interests of capitalist exploitation today. Imperialist entrepreneurs like Cecil Rhodes are seen as yesterday’s valuable job creators. The colonisation of human life by capital is just another beneficent development project.

For this reason it is in the interests of various sectors of the ruling class to exert influence over people’s understanding of history. It may not be a straightforwardly white-supremacist agenda. It may, on the contrary, take the form of coldly scientific-seeming economic reason. For example, consider the way the Economist‘s rescinded review of Edward Baptist’s book, The Half Has Never Been Told, attempted to defend fundamental assumptions about the nature of capitalism – that capitalists could never have abused their ‘valuable property’ the way Baptist argues they abused their slaves.

When he was education secretary, Michael Gove tried to implement a new school curriculum that made pride about British imperialism explicit. Taking inspiration from a children’s book first published when Edward VII was Emperor of India, Gove wanted schools to teach “our island story,” portraying Britain as “a beacon of liberty for others to follow.” What horrified professional historians, but shouldn’t have shocked them, was the brazenness with which the government saw historical education as an ideological project.

But the school curriculum isn’t the only way to influence people’s understanding of the past. It’s probably pretty ineffective, and of course Gove’s attempted reforms can hardly be blamed for the recent poll of adults’ views. Much more important is the media apparatus through which public knowledge and historical narratives are constantly reiterated – newspapers, popular paperbacks and television.

Historians such as Dominic Sandbrook and Niall Ferguson, drawing on the prestige of Oxbridge doctorates, populate the airwaves and the columns of the Daily Mail with eulogies to empire. The shelves of popular history are dominated by male authors and by particular, predictable topics. Max Hastings, Bernard Cornwell, Anthony Beevor and Boris Johnson all currently feature in the Waterstones’ top ten history sales, with books on Churchill, the Second World War and the Battle of Waterloo. In the popular consciousness, the British empire’s ‘finest hour‘ is replayed over, and over, and over again. Its tragedies are, of course, largely ignored.

What and who gets published are marketing decisions – but let’s not kid ourselves that publishers don’t shape consumer behaviour just as much as they follow it. Penguin Random House accounts for 23.4% of Britain’s book sales. It’s owned by Pearson, the textbook publisher that also owns the Edexcel exam board. Until recently, Pearson also owned the Financial Times and a 50% stake in the Economist. Even if it is exercised with the greatest of subtlety, such corporations have enormous power over the way history comes to be represented in school, in bookshops, and everywhere else. That’s how ideology is shaped.

There are alternatives to Ferguson and his ilk. There is a long and deep tradition, fostered not least among scholars of colour like Eric Williams and C.L.R. James, of history-writing that seeks to expose the structures of imperial and capitalist exploitation. But it will take a lot to give this critical perspective the same exposure given to the defenders of empire. There’s a war of position taking place in the academy, and in the media, in politics, and in the public sphere at large. When I begin to wonder what good I could ever do as a historian, it’s polls like this one that remind me how much important work there is still to do.

Photo: Willoughby Wallace Hooper, taken during one of many British-induced famines in India/Wikimedia Commons

–

If you want to support media for a different politics, you can donate or subscribe to Novara Media at support.novaramedia.com.