5 Problems with Effective Altruism

by Connor Woodman

7 June 2016

A network of groups, including Give Well, The Life You Can Save and 80,000 Hours – all under the banner of Effective Altruism (EA) – has sprung up in recent years promising to finally overcome well-worn critiques of western aid projects. Now, they promise, you can know that your donations won’t evaporate into bureaucratic opacity, lost to an oasis of inefficiency and corruption. Instead, powerful moral persuasion is to be combined with rigorous scrutiny of charitable outcomes: the quality-adjusted life years you’re purchasing for your buck.

Here are five interlocking problems with the EA approach:

1. It misframes the issue of global poverty.

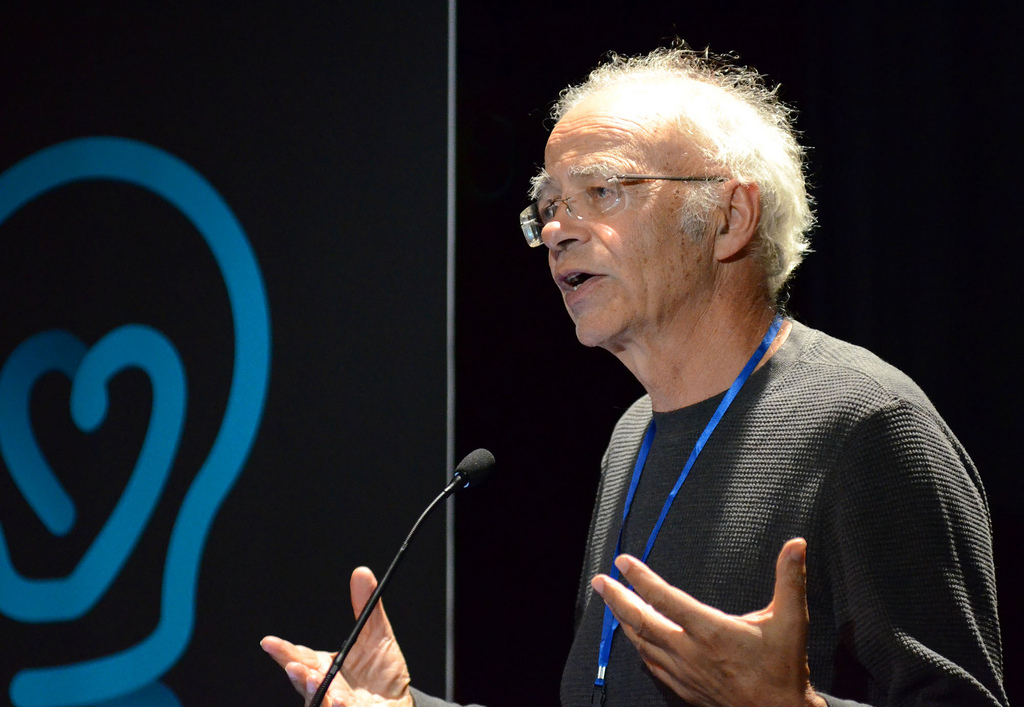

Peter Singer (pictured), EA’s intellectual godfather, famously asks what we should do if we stumble upon a drowning child in a pond, whom we can save only by ruining our expensive pair of shoes. Surely, he states, we have a stringent moral obligation to save the child, even if the shoes cost us £70. If this is so, he concludes, we must have a similar moral duty to donate money to organisations saving dying children in the Global South. Give effectively, he argues, and you can easily save numerous people from death without sacrificing anything of moral importance. This thought experiment has been taken up by EA and used to persuade would-be donors to up their charitable contributions.

The trouble is, global poverty isn’t like stumbling upon a drowning child whose predicament you have no responsibility for. In reality, there is a wealth of empirical evidence that global poverty is in large part caused by systems of western military, political and economic domination, both historically and contemporaneously. Colonialism, slavery, covert coups, IMF-impositions, World Bank-evictions, illegal invasions, unfair trade, off-shore systems of corruption and tax avoidance, corporate dominance, unjust resource extraction, exploitative labour relations, support for ruling elites – the riches westerners enjoy are largely the stolen property of those in the Global South. Our duties are more akin to negative duties to stop harming the poor, rather than Singer’s positive duties to assist. Obscuring this confuses reparation with beneficence, and results in EA’s advocacy work often missing root causes.

2. Its quantitative, individualist logic precludes necessary political action.

An amalgam of utilitarianism, rational choice and numerical quantification, EA operates through carefully calculating each donation’s expected lives saved. Insofar as this is a call for more strategic thinking and tactical planning, it’s to be welcomed; but the method actively precludes the kind of collective action necessary to make lasting change.

It leads to hostility towards causes with unquantifiable outcomes; combine this with the logic’s intensely depoliticised, individualistic orientation, and radical activism is largely out of the picture. One wonders whether the NAACP would have ever gone ahead with the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955 if its leaders had been Effective Altruists. Or if any large-scale uprising, grassroots social movement or revolution would have ever occurred under EA’s calculus. After all, intervening in the political sphere, building coalitions, and engaging in struggle are all inherently uncertain, and require a collective as well as an individual lens. Movements frequently fail. One must ask who the EAs would have supported in the run up to decolonisation: national liberation movements, or Victorian philanthropists?

3. It deals with symptoms, not structures.

Underlying these first two problems is a basic failure of political analysis. Rather than mobilise to smash the causes of world poverty, environmental degradation and militarism, EA wants only to patch up the after-effects.

Rather than ask why nearly 1bn people are undernourished in a world of abundant food, why more money is spent researching baldness than malaria, or why ex-colonies are forced to export their resources and labour to the former imperial metropoles, EA takes these facts as a given and asks how we can stop their worst effects. This deficiency leads some in EA to the mind-boggling conclusion that you should join Wall Street and give your salary to charity. There is no recognition of the role western banks play in facilitating the unequal global order. This is truly a dictate to steal from the poor with one hand and feed with the other.

This ties in with the network’s intensely individualised focus. The problem of world poverty is on your shoulders, Effective Altruists say, and you have to give your money to save it. Whilst this has to be part of the analysis – any action must stem from individual moral obligations – it neglects the collective responsibility we have to join together in a political movement to reform and overthrow the structures of exploitation and domination which cause these global horrors. Tellingly, one of the prime demands of the global poor – for redistributive land reform – is conspicuously absent from EA’s pronouncements.

4. Solidarity is a better moral framework than altruism.

‘Aid’ has paternalistic undertones. Instead, we should be looking to support and join in transnational solidarity with movements in the west and Global South: indigenous peoples, landless peasants, precarious garment workers. As Monique Deveaux puts it: “By failing to see the poor as actual or prospective agents of justice [EA’s approaches] risk ignoring the root political causes of, and best remedies for, entrenched poverty.”

The best way to show solidarity is to strike at the heart of global inequality in our own land. There are an array of solidarity groups that seek to change western foreign policy and support modern-day national liberation movements. There are also various western NGOs which seek to injure the production of structural injustice in the west.

Words like solidarity – along with class, imperialism and exploitation – are scrubbed from the EA lexicon. Perhaps they should relaunch as Effective Solidarity.

5. It absorbs the moderates.

Where once universities were hot-beds of political activism, students are increasingly attracted to the safety of RAG and EA. The hard political contestation, argument, struggle and conflict that comes with building movements which seek to challenge entrenched power is foregone for the easy route of charitable giving.

Movements need to bring in an array of actors from across the political spectrum, and gain more success when they’re able to draw in those perceived as moderate and respectable – something the Fossil Free campaign has done quite well. As Genevieve LeBaron and Peter Dauvergne outline in Protest Inc., the state increasingly cracks down on radical dissent whilst facilitating and co-opting more moderate political activity. EAs need to be acutely aware of this danger, and should at least show solidarity with those on their radical flank.

When your campaign is telling you join the establishment and work your way as high as you can, alarm bells should be ringing. I don’t advocate giving no money to charity – but Effective Altruism is presenting itself as the main solution to the world’s problems, largely dismissing the alternative of collective action to transform global structures of domination. Those who feel moved to action by the state of the world need to take radical grassroots movements more seriously, through both donation and participation.

Photo: Mal Vickers/Flickr

–

If you want to support media for a different politics, you can donate or subscribe to Novara Media at support.novaramedia.com.