The Labour leadership election has seen Jeremy Corbyn renew his proposals for rent controls, and the industry response has been as predictable as it is completely devoid of anything resembling the truth.

Alan Ward, the chairman of the Residential Landlords Association says that controls “would be a disaster for tenants.” He goes on to say Jeremy Corbyn is “ignoring all history and experience which shows that where such controls are applied they choke off the supply of homes to rent, making it more difficult for tenants to access decent and affordable housing.”

In his defence, there is an element of common sense to the idea that rent controls would damage supply; that the problem in the housing market is a basic question of supply-and-demand. The problem is that there is a full century of evidence from scores of countries about what the impact rent controls has actually been – and every single piece of it proves Alan Ward wrong.

1. ‘Rent controls were a disaster when they existed in the UK’.

Landlords insist that the various rent controls which existed in the UK between 1915 and 1988 were disastrous for tenants. They point out that, over those 70 years, we went from almost nine in ten people renting privately to fewer than one in ten. They claim this is proof that rent controls devastate the private rented sector (PRS).

But that change, by absolutely any measure, was an enormous success of public policy. The reduction in the private rented sector can be explained in three obvious – and positive – ways:

- Millions of council homes were built to give people a secure, safe, affordable place to stay outside the PRS.

- Millions of people were able to buy their own homes through real-terms increases in wages and the expansion of mortgage availability.

- Millions of the properties that landlords were renting out were demolished in slum clearances because they were, well, slums.

All of these changes were the deliberate objective of successive governments, both Labour and Conservative, which sought to reduce the amount of people in the private rented sector because they recognised it was the worst of all tenures.

Pointing to the relative decline in the PRS as evidence of the failure of rent controls is – if we are being charitable – lazy and stupid. In reality, it is a deliberate lie.

2. ‘Rent controls been a disaster everywhere else they’ve been tried’.

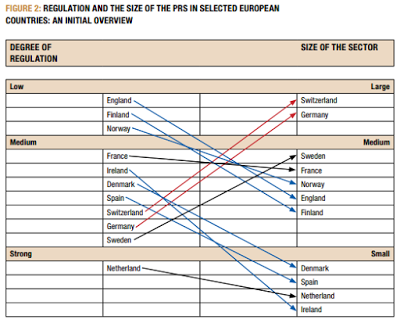

Again, this is nonsense. In fact, across Europe there is a clear correlation between how heavily regulated a country’s PRS and how big it is. These two charts from the Cambridge Centre on Housing & Planning Research speak volumes.

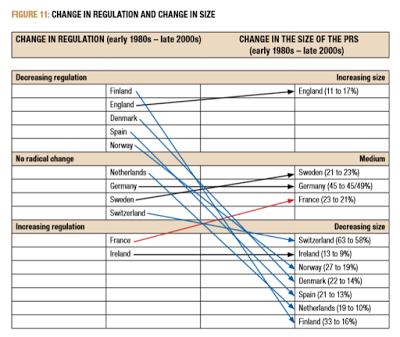

Firstly, there is a positive correlation between regulation and size – the biggest private rented sectors are the most heavily regulated.

And secondly, there is no evidence whatsoever that decreasing regulation leads to an increase in size over time. The UK is the one exception to this, and that is attributable more to other factors – the explosive rise of buy-to-let mortgages for example, than to deregulation.

3. ‘All economists agree that rent controls are bad’.

You’ll often hear comments bandied around claiming that all economists agree rent controls are unambiguously bad. There is a grain of truth to this – a poll from 1992 showed a surprising degree of consensus that rent controls would have negative effects.

But here’s the hitch. Nobody is proposing the type of rent controls that this supposed unanimous opposition is directed at – and certainly not Jeremy Corbyn. During the first world war, what are now called ‘first generation rent controls’ were brought in across most countries involved in the conflict – these were blunt caps or freezes on rent, and are rightly criticised for having negative side effects. But now we have 70 years of evidence from across the world about how to implement rent controls without unintended consequences.

In his article ‘Time for Revisionism on Rent Control?’, Richard Arnott, a Boston economics professor, says: “Economists’ traditional opposition to rent control is based on a combination of ingrained hostility to price controls and the experience with first-generation controls.” He goes on to conclude that “second-generation rent controls are so different that they should be judged largely independently of the experience with first-generation controls.”

4. ‘All landlords would leave the sector and tenants would have nowhere to live’.

Landlords threaten to leave the sector if regulation is increased, but a quick glance across Europe is enough to dismiss this: the most heavily regulated private rented sectors are consistently the biggest. Germany, with the biggest PRS in Europe, is easily one of the most heavily regulated.

Besides, a huge portion of the income landlords receive from their properties comes not in the form of rental income, but income from capital gains – the value of the properties themselves increasing. With house prices predicted to continue to spiral, any reduction in rental income would have a negligible impact on the profits of landlords.

But perhaps most importantly, the properties these landlords are currently renting out already exist. Unless these landlords left these properties abandoned, leaving the sector wouldn’t impact on supply at all.

5. ‘Rent Controls would stop new homes being built, making the supply problem worse’.

Almost all the properties that have come into the PRS during its expansion since rent controls were scrapped in 1988 have been pre-existing properties which simply changed hands – going from being either social housing or owner-occupied to being bought up by landlords and rented out. Even the British Property Foundation (vehemently opposed to rent controls), as well as the Conservatives, accept that the PRS is not leading to new homes being built.

There are also plenty of examples of rent control models which explicitly exempt new-builds from elements of the regulation; that was the case in Britain for many years and is currently the case in the Netherlands.

There’s lots that could be done to incentivise new-builds, but two things are clear: deregulation in the PRS isn’t the answer, and rent controls aren’t a barrier.

Photo: Alex Pepperhill/Flickr

–

If you want to support media for a different politics, you can donate or subscribe to Novara Media at support.novaramedia.com.