Momentum, the organisation set up following Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership campaign, now has over 20,000 members and has had major successes in its first year. Over the past few weeks, it has been embroiled in a wrangle about process and structures which has acted as a lightening rod for several other tensions.

As a member of Momentum’s first steering committee, these are my (obviously partial) initial thoughts on what should come next. Far from seeking to ‘settle’ the questions that have emerged over the past few weeks, what Momentum needs is a collective understanding that its future will be forged in a process of mass negotiation.

1. Acknowledge the politics of the situation and embrace the contradictions at the heart of project.

The ‘clever’ way to engage in the current debate around Momentum’s structures is to attempt to define Momentum’s purpose and work back from first principles. Logical as this may sound, it is also not particularly helpful – because there is no especially meaningful answer to the question ‘what is Momentum for?’ other than what is already obvious.

Over the coming years, we will work out the balance between its two broad functions – on the one hand working ‘in and for’ the Labour party, on the other hand as a freestanding social movement builder – but we will only do so in the process of actual struggle (and with very different results in different areas of the country and areas of activity), not in the throes of a bitter, abstracted structures debate.

On the other hand, understanding the deeper motivations behind the current dispute is important – because otherwise the real debates will be ensnared in the toxic power struggle that emerged recently, in which a short-notice meeting of Momentum’s executive (the steering committee) voted to postpone a meeting of the legislature (the national committee) and unilaterally decide to establish Momentum’s constitution by online vote. If we confuse the substantive debate with the petty squabble, we will have a confused discussion and alienate thousands of members.

What Momentum needs, then, are structures that can allow for flexibility in its purpose and which can hold together the broad coalition that exists inside it.

2. Stop trying to claim the ‘new politics’.

The defining antagonism inside Momentum, nationally and locally, is a culture clash between the people who have been around forever in the Labour party, and people who have recently joined or become active.

In many local groups, the two clans are thrown into the same organisation, sometimes harmoniously and sometimes not. At varying speeds and with varying levels of acrimony, the insurgent left has challenged the old Labour left’s organising culture and leadership, while largely adopting its primary aim – transforming the party.

The divisions over e-balloting versus physical meetings simply do not map onto these differences. Jon Lansman, an old Bennite, is the strongest proponent of a 100% online democratic system. Other old Bennites find themselves on the other side. Young social movement veterans like me are on both sides, and in the middle – some want as little structure and as few meetings as possible, but others have seen the centralising and depoliticising role that referendums can play in (for instance) student unionism. On the steering committee, I often find myself being lectured about how amazing the internet is by people who, suspiciously, don’t know how to use it very well.

More broadly, the rhetoric in the current debate about Momentum’s structures is threatening to polarise the organisation between two make-believe camps: the ‘hard core’ who hoard power in meetings and the ‘clicktivists’ who want to define the organisation without contributing to it. We cannot afford to write off people’s engagement in this way, or for ‘activist’ to become a dirty word.

3. Stop talking about ‘Trots’.

When Paul Mason wrote about the future of Momentum last week, perhaps his most striking concern was that we might reach “a scenario where die-hard Bolshevik re-enactment groups decide to take over Momentum, so that it can then take over Labour, and then Labour takes over the state.”

This idea goes some way to explaining the fact that the most prominent advocates of online voting as a means to prevent organisational capture are not from the younger generation of Corbynites. Mason and Lansman could not be further apart on many of the key questions facing Labour (on progressive alliance, electoral reform, Trident). What they have in common is that much of their early political experience was in the 1980s, when British Trotskyism was a major force in the Labour movement. When Lansman ran Tony Benn’s deputy leadership campaign, he had to negotiate a labyrinth of sects which ran whole city councils and had thousands of members nationwide.

Now, the most influential – and very well-reported – Trotskyist group in Momentum is the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty, and it has barely 100 members. Its representation in Momentum stretches to two members of a 50-strong national committee and one member of a 12-strong steering committee. If you wanted to be uncharitable, you could say that at some deep unconscious level it might want to ‘take over’ Momentum, but its size and political culture makes it, in effect, a pressure group. There are no Trotskyist organisations left in Britain that can achieve anything remotely resembling a ‘take over’. The biggest two – the Socialist Workers’ party and the Socialist party (formerly Militant) – are a shadow of their former selves and are already banned from Momentum.

Promoting the idea of a ‘hard left’ or ‘Trotskyist’ capture of Momentum really just amounts to the use of a spectre whose only existence is in the imagination of the Labour right and a hostile press. Ditto the allegation that a delegate structure constitutes a ‘party within a party’. People should know better than to regurgitate this stuff.

4. Embrace a mixed system of democracy.

Online voting and delegate systems both have flaws.

A democratic system based purely on attending physical meetings and electing delegates will mean that decisions are only made by people who show up. But assuming turnout is not 100% in an online vote, the voters will also be self-selecting; their participation will be affected by their computer literacy, their ability to watch a live stream, or how well they check their emails. In elections, the face-to-face system favours candidates who speak well, or do lots of local activism, or have been around a while, or have a caucus of people they can line up to vote for them. Online systems favour candidates who have lots of good networks, have big names, or know how to use social media. Once elected, the people elected from delegate meetings will feel much more accountable to the meeting which elected them; the people elected online will have a bigger mandate numerically, but they won’t answer to their constituency in the same way.

Both systems have failings when it comes to the quality of engagement. A pure delegate system will make the quality of engagement dependent on the existence and quality of your local group. An online system will make it dependent on your ability to digest the issues without hearing a debate around them, from behind a laptop. The atomisation that this creates has been mitigated by the march of technology and social media, but it has not gone away – it means that people are more likely to be swayed by the mainstream media and more likely to be politically conservative. This is why the Labour right was such a big proponent of ‘one member, one vote’ (OMOV), and was one of the reasons why Margaret Thatcher forced unions to ballot by post to go on strike.

For instance, the proposals going to February’s founding conference will, necessarily, be complicated. Unless voters are very engaged in the debate – the kind of engagement that comes from being a delegate or attending a local meeting – many will vote for slogans, not for the substantive proposals. In the absence of a proper culture of internal bulletins and online forums, they will may well vote for whichever slogan is supported by prominent bloggers and big names in Momentum.

The power structures produced by each system have problems. The ‘layer cake’ version of the delegate system that Momentum currently uses makes it very difficult for individual members to have a direct impact on the organisation. But that doesn’t change with a pure online system – if anything it gets worse. Without a central deliberative body of some kind which is directly responsive to members, power lands in the hands of the executive, or whoever happens to be in the office. Without the power to actually influence decisions, activists will leave and local groups will wither.

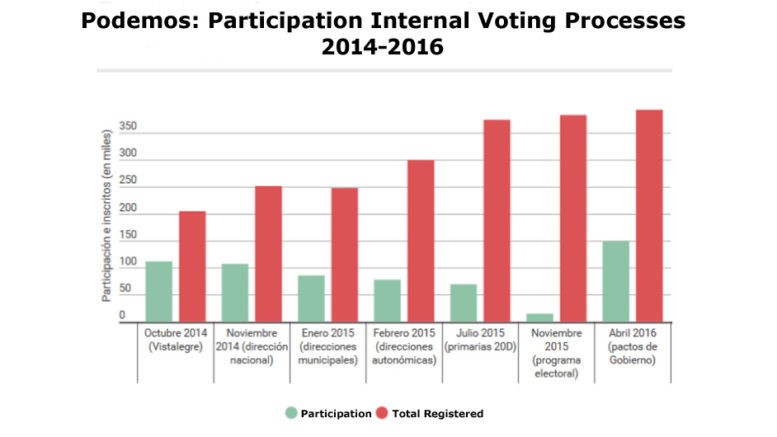

A primarily OMOV system does not guarantee the health of an organisation in terms of individual participation, either. Below is a graph showing the voter turnout in the internal polls of the left-wing Spanish party Podemos. As a proportion of the membership, participation has fallen sharply and never recovered to its initial height.

The answer to these problems is not to give up on making Momentum democratic – it is to fuse the two systems. Doing so will not only help to hold the organisation together, it will also open up participation. Electing a national committee and an executive using online ballots and face-to-face meetings will mean that members have lots of different ways to get elected and get involved.

Making big decisions using both a sovereign conference and an online vote will have the advantage of engaging more people and doing so directly, but mitigate against the atomising and centralising effects of OMOV. Rather than have online ballots called on issues willy-nilly over the heads of activists, we should call them as part of the annual conference process, or as a ‘national conversation’ triggered by a certain number of local groups.

The same should go for Momentum’s founding conference in February. A full-blown delegate conference should take place, with delegates elected from local groups. Those delegates should first narrow down the constitutional proposals to two or three, and then vote on them. Their votes should then be advertised to the membership, and then an online ballot should take place. The delegates and the members should each have their votes weighted at 50%.

5. Establish basic democratic norms.

Above all the noise about structures and voting systems, it is urgent that there is a democratisation of the ‘centre’ in Momentum.

The decision to effectively replace Momentum’s conference with an online ballot was taken at a steering committee meeting called with less than a day’s notice. This was then half-reversed, and the decision handed back to the national committee. All of this is exasperating for an activist base which has never seen any minutes of either a steering or national committee, and which has no readily available information about Momentum’s structures or who runs the organisation.

The left and the labour movement are not new to all of this, and ought to have a grip on some basic democratic principles: all members have the right to know who their representatives are, what their powers are, how to contact them, and what decisions they have made. There should be rules about who can call meetings, how, and at what notice.

Another basic principle: the only formal power wielded in an organisation should derive from a democratic mandate from members. At the moment, a significant part of Momentum’s national committee is not elected but appointed by external organisations. This should be abolished. We also need to address its elaborate corporate structure. At present, Momentum is an ‘unincorporated association’, but all its data and money is owned by two separate limited companies. These two limited companies have completely independent directorships from Momentum, meaning they could act independently.

The same principle needs to apply to what Momentum does in Labour. Gone are the days when candidates could be decided and slates put together behind closed doors by a series of experts. The candidates that Momentum backs – at a national level, at a regional level and in youth and other sections of the party – should be chosen in a process decided by its democratic structures. This isn’t to say that we should not back candidates from beyond Momentum’s ranks, but it should be up to members to make the decisions.

Momentum has the potential to transform British politics – bringing hundreds of thousands of people into Labour and millions to the ballot box, while facilitating social movements that can shift the discourse and change minds. Doing all of this – understanding and embracing the differences that exist in Momentum, using a mixed democratic structure, and laying down some basic democratic expectations – will not make everything better, but doing so is a prerequisite for creating a participative, energetic organisation.