Werker Collective and the Worker Photographers: Taking Back Control of the Image

by Charlie Clemoes

15 April 2017

The past year has seen the rise of a new form of right wing populism. Its ability to ride the wave of popular discontent and exploit the openings afforded by new media compels the left to think seriously about how to communicate its message. To do so it must find new ways to depict the world on its own terms.

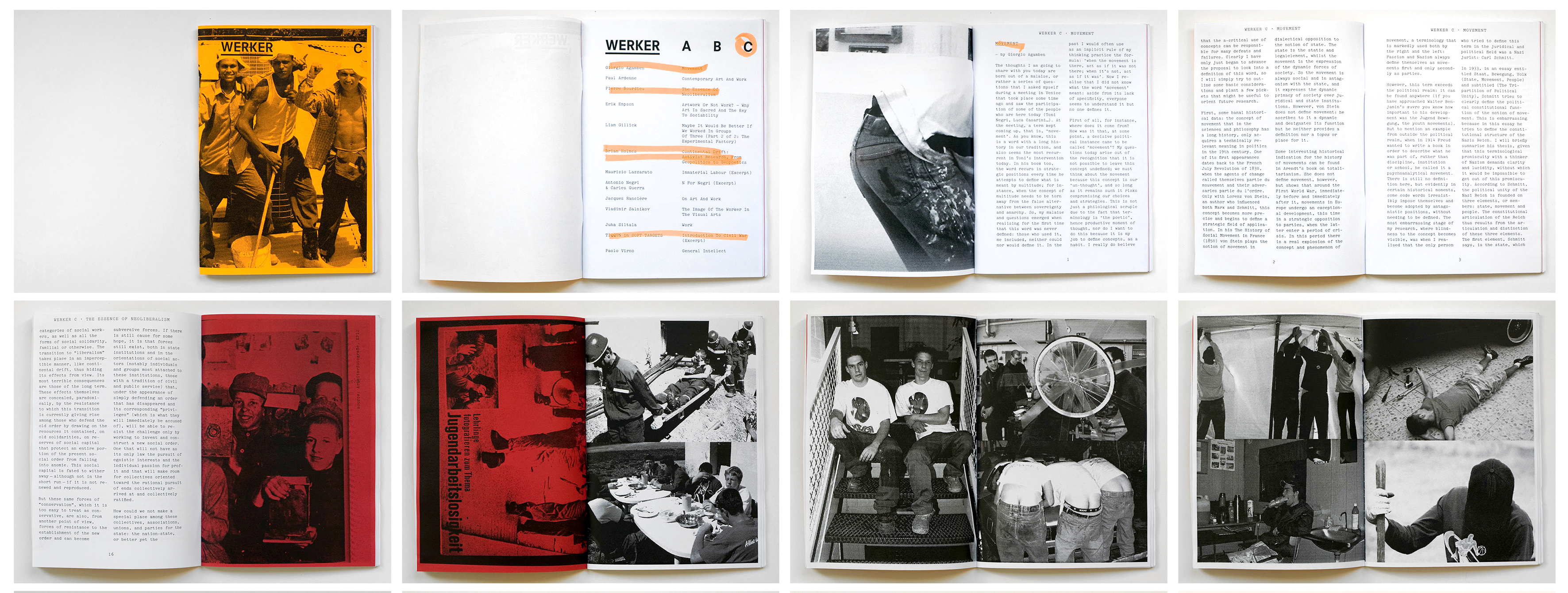

Through a sustained attempt to rehabilitate the Worker Photography movement, Werker, an Amsterdam-based art collective, offers some timely lessons for how to respond to the current situation. Founded by artists Rogier Delfos and Marc Roig Blesa, the collective began just as the financial crisis hit in 2008 and has grown to encompass a series of ongoing projects.

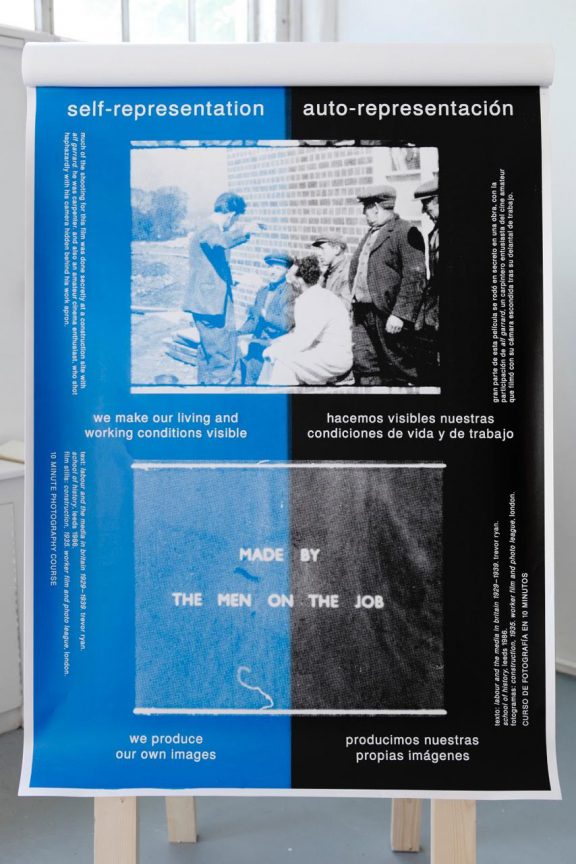

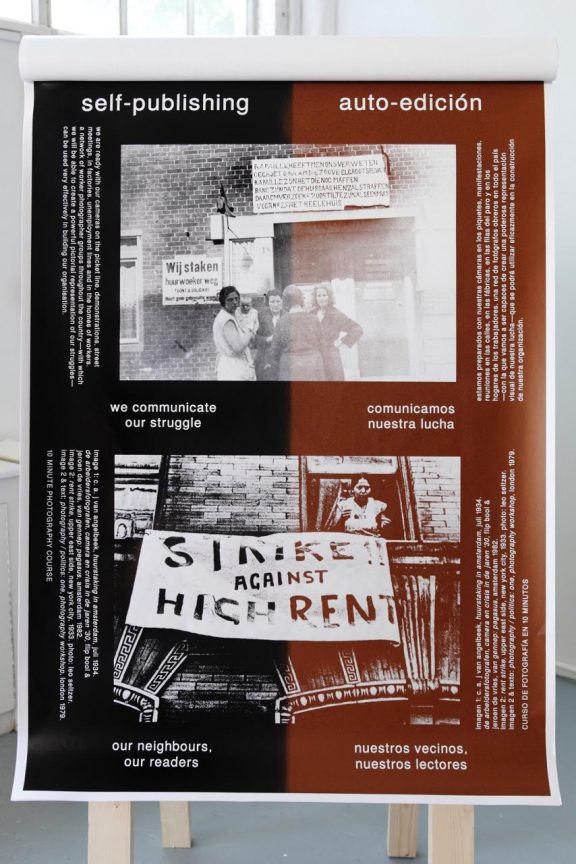

The intention of the original Worker Photography movement was both to inject intellectual rigour into amateur photography and combat capitalist hegemony over the image by depicting aspects of life that would otherwise go under-represented. Werker seek to adapt these aims to new media and new developments through a range of workshops, publications and exhibitions.

The differences between then and now are undoubtedly many, but there are also some compelling parallels. Emerging a century ago in Russia and spreading across Europe in subsequent decades, the original movement reached its zenith during the rise of fascism in the 1930s. At this time, the ordinary person was newly capable of accessing tools to produce photography that had hitherto been too costly. Even so, rarely did amateur photographers succeed in challenging the visual representation of the world offered up by the capitalist-owned media. This is arguably the case today too, even though the use of photography has increased exponentially in the past decade.

Writing in 1931, the German communist leader Willi Munzenburg identified the Worker Photographers’ particular mission: “Thirty or forty years ago, the bourgeoisie already understood that a photograph has a very special effect on the viewer […] Just as the workers of the Soviet Union have learnt to make their own machine-tools, to invent things themselves to be put into the service of peaceful socialist construction […] so the proletarian amateur photographers have to learn to master the camera and to use it correctly in the international class struggle.”

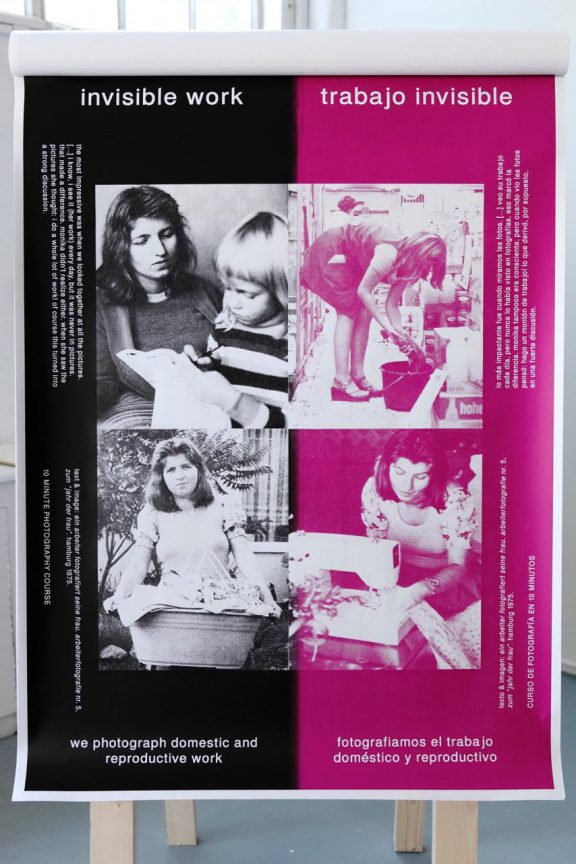

This required the same kind of organizational response we need now, encompassing a commitment to educating as many people as possible in the basic principles of photography and image representation. What the Worker Photographers lacked in glossy, expensive images, they made up for with representation of a wide range of experiences of what was actually happening in the world: the drudgery of domestic and reproductive work in the home, conditions in factories, unemployment lines and demonstrations, but also ordinary people sharing moments of collective joy.

Since they started in 2008, Werker has proved to be progressively more pertinent and led to a remarkably diverse array of projects. Specifically, they have taken on board the Worker Photographers’ distinctly forward-thinking focus on how to reproduce the conditions for continuing to realize the project’s aims, through self-organization, non-authorship and, most importantly, what the original photographers described as ‘bilderkritik’ (image analysis), whereby amateur Worker Photographers send in their photos to be critiqued, not only formally but also conceptually.

A running theme in Werker’s projects is the aim of developing people’s critical eye, especially as it concerns their workplace and their housing. As early as Werker 3, they began with a call “for students, artists, domestic workers, housewives and husbands, designers, cleaners, architects, au pairs, researchers, gardeners, theorists, pool-boys, historians, employers, interns, curators and handypeople”, asking them to “think politically about [their] domestic space.”

Despite departing from the original Worker Photographers’ tendency to focus on traditional conceptions of what constitutes work, the aim is ultimately the same: to reveal something about life and work that current mainstream imagery does not represent, to make the invisible visible, and thereby lend it a political resonance that serves as a resistance to dominant representations in the media.

Yet this is only half of their project. It is not only that under-represented aspects of work need to be better represented. Nor is it only that workers must adopt a more rigorous approach to image-making. It is also that those already purporting to possess a rigorous political approach need to be more aware of the specific power of the image. As Werker’s founders emphasize, the left has for too long been attached to materialist arguments. Instead, echoing Munzenburg’s remarks, they stress that we need to think carefully about how the image works, what effect it has on people and how this effect can be utilized to enhance the sophistication of the left’s message.

This is well represented in one of their earliest projects, Werker ABC, in which they juxtapose images of young men at work, assembled from different sources on the internet, with contemporary left wing theory about labour, also derived from the internet. Whereas searches for young male labour often produce quite theoretical textual representations, Werker produce distinctly homoerotic visual representations of the same theme.

Pairing the two underlines how differently we interact with the image and how much the image conveys elements of desire that are often overlooked in the left’s message, and often dismissed as trivial. As Roig Blesa has stated, it is in the realm of desire that the left loses, “because capitalists always appropriate desire as a way to articulate visual language. And the left sees desire as something that is misleading.”

Werker’s most recent iteration, Werker Correspondent, is a worthy culmination of their work so far, fusing these two sides well. The project begins with an initial focus on generating direct information of the urban realities in north African cities, the intention being to generate a mail art network, a platform to encourage the exchange of images in the context of south-to-north and north-to-south relationships across the Mediterranean.

According to the project’s description, in contrast to the stereotypical representations of the Arab world in traditional media and official relations on a political and bureaucratic scale, Werker and its collaborating photographers “look for different kinds of images and affections. Proposing empathy and solidarity in contrast with clashing civilizations. Everydayness and internationalism in contrast to the notion of otherness. Autonomy and self-representation in contrast to dominant media.” Still in development, the project will evolve independently throughout subscriptions that would allow its continuity, financing the production and shipment of photographs, as well as the photographers’ remuneration.

All Werker series are ongoing projects, from Werker ABC to the most recent Worker Correspondent. All are open to new additions. As such, there are many ways for people to participate.