Eduardo Chibás: The Life and Times of a Populist

by Felix Holtwell

30 April 2017

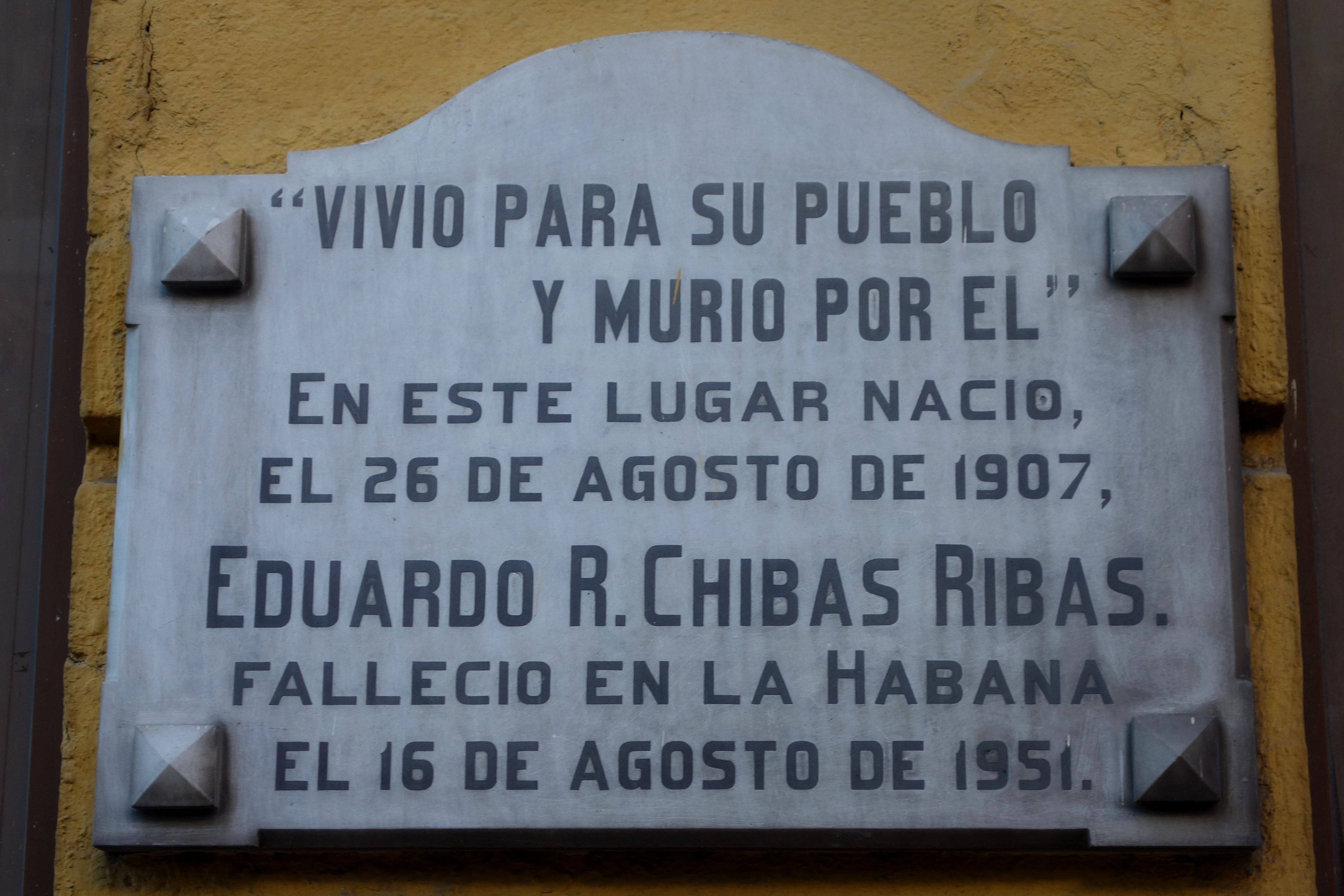

Eduardo Chibás was a post-war radio star, cuban politician and populist. He managed to rapidly build a movement by using new media – a movement which collapsed after his death. His life illuminates the possibilities and limitations of left populism.

On the morning of August 5th 1951 Eduardo Chibás was, together with a friend, preparing a radio broadcast. At one point the cuban politician pulled out his pistol and asked if his guest wanted to see if his shot could reach the sea from his seaside Havana mansion. After a negative reply, Chibás put the gun away but a bullet fell out. When his friend picked it up and asked to put the bullet back in, Chibás responded: “That’s all right, I already have all I need.”

In the evenings, Chibás would usually walk with a group of friends to the radio studio. He chatted with a crowd of onlookers, his trademark as a politician being personal contact with the people. His talk was preceded by one of José Pardo Llada, future comrade, and afterwards opponent, of Fidel Castro. Surrounded by his followers, Chibás then began the show.

All of this was normal to Chibás. He had pioneered political radio in Cuba. His shows generally combined fiery attacks on opponents with muckraking journalism which focused on scandals. He hosted the most listened-to political talkshow on the island, and sometimes could compete with the overwhelmingly popular broadcasts of baseball games.

But on August 5th, he went over his assigned time limit, he was cut short and an advert for a Café Pilon began. Unaware, Chibás continued shouting into the microphone, ending with: “People of Cuba. Rise up and walk! People of Cuba, wake up! This is my last loud knock.” He then shot himself in the belly, causing an uproar in the packed radio studio. He was rushed to the hospital where he died eleven days later.

At the time Chibás was, according to polls, one of Cuba’s most popular politicians, and a prime candidate for the presidential elections of 1952. Chibás had started his political career during the 1933 cuban revolution. Disappointed by the corrupt rule of his party in the wake of the second world war, Chibás left the Partido Revolucionario Cubano (Auténtico) to found his own: the left populist Partido del Pueblo Cubano (The Cuban People’s Party) or ‘Ortodoxos’, which rapidly became highly popular. After his suicide, under the pressures of the political coup that followed, the movement disintegrated. During the coup, Fulgencio Batista, a rival of Chibás, took power. In the face of Batista’s reforms, which stripped away civil liberties and routed rival parties, Orthodoxos collapsed. Batista only ceded power after being ousted in Cuba’s 1959 revolution.

Eduardo Chibás provides a prime example of what could be termed an actually-existing left populism. Chibás advocated for redistribution, economic nationalism and popular participation in government. By focusing on corruption scandals and the wrongdoings of a landed elite, he constructed a discourse that united diverse groups and classes; forming an ‘us’, in opposition to an elite, corrupt ‘them’. He did this through extensive use of new media, and used it to jumpstart a political movement.

This terrain of struggle is strikingly familiar – so perhaps it’s useful to turn to this historical moment for lessons for our troubled times. In times where the European left struggles to formulate a populist politics that can hold back the right of right-wing nationalism, Chibás’ life is a lens through which we can see both the possibilities and the limits of left populism; that it can fuel explosive growth, but also introduces weaknesses into political movements.

New media.

Chibás’ core resource was new media. Radio had been introduced in Cuba during the 1920s, and had rapidly spread by the 1930s. Direct contact with his listeners was key to Chibás’ activism. In one case he asked listeners to send him cases of school corruption after a corruption scandal started spreading in the government’s education department. Letters came in decrying shortages of all kinds of school materials: paper, pencils, books, desks and water filters. Most of the money for it had been diverted into private accounts of top politicians. One letter described government-backed gangsters coming into schools disguised as state inspectors, and threatening staff. Another how material and manpower destined for building a school was diverted to the personal property of the education minister.

Chibás aired these types of testimonies on his show and used them to attack the government. He used radio as a conduit for his supporters, but also to bind them to him. By having cubans send him testimonies of injustice he would fight for them, but also provide a platform for their voices to be heard. One of Chibás’ most notorious media episodes was his crusade against the cuban Electric Company. The US-owned company had long enjoyed preferential access to the cuban market and used it to extract high rents from the population. In 1948 citizens of Puerto Rico payed $9.85 per electric kilowatt – whereas Havana residents paid $16.45. This ceaseless, grabbing attitude towards the people of Cuba earned the company the nickname of ‘the electric octopus.’ When this octopus again raised electricity rates, and a court case failed to overturn the raise, Chibás sensed opportunity. He had previously called for the nationalisation of the company and now he accused the judges who failed to overturn the raise of taking bribes. Chibás declared:

“Once again the cuban people have been disgraced because money has won out over shame. The ever growing mud hole of corruption invading the country has now reached a place we never thought possible: to some of the Supreme Tribunal judges.”

He was subsequently persecuted and fined for his comments about the judges. He was undeterred:

“Since I never enriched myself in the government, nor did I rob, deal in the black market or enter into business arrangements with Grau’s [leader of the Auténticos] henchmen, I don’t believe I’ll be able to pay the fine.”

Afterwards, he organised mass rallies only illuminated by candles and kerosene lamps, a symbolic rejection of unaffordable electricity. He did eventually serve a short jail sentence for his attacks. But because of the unpopularity of the Cuban Electric Company, and his extended dramatisation of the events, this stint in jail only served to strengthen his popularity. Not simply because of the unpopularity of the price raise, but also because he could whip up a sense of cuban indignation in the face of exploitation by a US-owned company.

“The recognition of his own people above all else.”

Direct, genuine contact with the crowd was Chibás’ trademark. His radio show used direct engagement with followers to great effect. This direct contact extended, however, farther than his media presence and engorged his public persona. He would embrace his supporters after political meetings. During a meeting in Santiago de Cuba, in which then-Ortodoxo Fidel Castro warmed up the listeners, Chibás’ first speech was met with “delirious acclaim and applause” according to a party activist. Afterwards, he jumped headfirst into the arms of the crowd. These sorts of actions, where he would “bathe” in the cuban people, proved a major break from distant, corruption-drenched cuban politics.

Young Fidel Castro would proclaim:

“This lunatic, out of sublime craziness for the sublime ideal of an improved Cuba, values the recognition of his own people above all else. He would be incapable of disappointing the devotion professed by the masses, as that would deprive him of the very oxygen he breathes. The day Chibás senses a reduction in citizens’ affection he would put a bullet through his heart, not out of cowardice in the face of failure, but so that his self-sacrifice ensures the victory of his disciples. No uncertainties! We are in the presence of a great man!”

When he went on tour outside of Havana, people would customarily greet him by trying to give him their identity cards. This was a normal scene for mid-century cuban politics, where politicians would take the identity cards to vote in that person’s place. The politician would then give favours to the person who gave them their identity card, such as securing their son a scholarship for university. Chibás and the Ortodoxos made a point of not accepting the cards offered to them.

His use of radio should be seen in this context. When Chibás set up a new party, outside of state power and unable to hand out patronage, he bypassed the system through radio and charisma. This allowed him to build up a following without having the resources to hand out favours. An approach that worked: a May 1951 poll showed him as the most popular presidential candidate by more than 10 percentage points.

Ideology.

Chibás could be defined as centre-left. He was an admirer of US presidents Roosevelt and Truman. Most of the policies he proposed as an Ortodoxo were the same as the ones originally proposed by the Auténticos. The Ortodoxos and the Auténticos were parties that combined centre-left policies with an (economic) nationalist tendency. Both parties aimed for a national economy not dependent on foreign powers that was redistributive in its orientation. They also referred back to nationalism and the national past, often to the recent cuban revolutionary war of independence. The 1938 nationalisation of Mexican oil by the Partido Revolucionario Institucional also figured prominently in the thinking of Chibás.

In his programme Chibás talked about social justice and the “betterment of the working classes” but for the ultimate purpose of ‘conciliation of capital and labour.” He supported rural development for the impoverished countryside, public works programmes, a public bank, less foreign involvement and diversifying the cuban economy away from dependence. But eventually he remained within a capitalist framework.

Chibás was also an anti-communist, his politics advocated for a road between capitalism and communism. As such he claimed that reconciling classes would stop communist infiltration into Cuba. With this strange mix of a left-populism with discourse that explicitly rejects ideas of class war, Chibás illustrates Laclau’s point that populism has little specific ideological content. Rather, it can exist on both the left and the right, or even in the ever-shifting centre ground. .

Laclau also highlights populism’s tendency to want to unify classes: a tactic that appeared in Chibás’ thinking. Through Ortodoxos, he managed to speak to diverse sections of the population, and unite them in their opposition to the political elite – not cast in terms of class in an economic sense, but in terms of their imbrication in the corruption at the heart of cuban politics. He also spoke about social justice for the working classes, and attacked the gang violence hindering the advancement of the petit bourgeois middle class. He was popular among the rural population, promising to deliver basic material goods such as concrete floors – something slated but not enacted by the Auténticos. He recruited Afro-Cubans, and set up an election headquarters in the gymnasium of famous Afro-Cuban boxer Eligio Sardiñas.

Building the party?

With Chibás as their leader the Ortodoxos rapidly became popular – but the party apparatus remained weak because of its reliance on Chibas’ personality. Thus, when he died, the party floundered, with no resilient democratic structure. In the last year of his life, Chibás went on a trip to the city of Guantanamo. The purpose of the visit was to prevent a scandal from breaking out involving the mistreatment of workers at a plantation he had inherited a small share in. He also used the trip to inaugurate the Guantanamo office of the Ortodoxos. Four years after the party’s founding, Ortodoxos only then possessed a small local headquarters in the mid-sized city of Guantanamo – even when Chibás was topping the polls. This was by no means an exception for the party; when it came to building up resources and creating a party infrastructure, they lagged severely behind.

Some have suggested that Chibás’ on-air suicide was a stunt aimed intended to unite the party – or a grand apology note after failing to provide evidence supporting his claim that education minister Aureliano Sánchez Arango had been embezzling public funds. Whatever the truth, his sudden death left a party floundering, unable to organise ordinary people to provide meaningful resistance to Batista’s authoritarian regime. It shows that you simply cannot rely on personal popularity to build a lasting populist movement. The reliance on the politics of the single spokesperson, the charismatic figurehead, distracted Ortodoxos from the effort of movement building. Such efforts are decidedly unglamorous, sometimes tedious, but absolutely vital. Without them, an unexpected event can mean a major setback for the entire movement. A great man approach is vulnerable to the failings, and ultimately the humanity, of whatever ‘great man’ accedes to the limelight.