How Young Voters Could Defeat the Tories in Key Marginals

by Mark McDonagh and Claire Frank

14 May 2017

Those aged 18-25 are least likely to turn up to the ballot box on 8 June. They’re most likely to feel disillusioned with mainstream politics and they’ve been at the brunt of countless cuts. Yet their voting power could significantly alter the predicted outcome of this general election. If there was ever going to be a time when young people should feel galvanised to vote, it is now.

Through analysing Electoral Commission, Office for National Statistics (ONS) and national polling data, we estimate:

- Under-25s can have a significant impact in defending Labour marginals and counteracting the impact of Ukip voters defecting to the Conservatives.

- Of Labour’s 57 identified marginals, 32 can be saved if Labour can hold position and get progressive young people to turnout at levels comparable to the national average.

- In Conservative marginals, 12 could be ripe for the taking by either Labour or the Liberal Democrats if large enough numbers of under-25s can be mobilised in those constituencies.

- There are eight Conservative seats particularly susceptible to a higher under-25 turnout, with high numbers of young people combining with a strong Remain vote from the EU referendum.

In summary, one of the major trends anticipated in the forthcoming general election is a significant shift of Ukip support from the last general election to the Conservative party. This is reflected not only in polling but in recent local election results. Less observed, but equally as important, is the potential for younger voters to counteract this trend. Were youth turnout to increase in a manner seen in the recent EU referendum, significant Tory gains – even with a historic boost from Ukip leavers – could be mitigated. The complexion of the next government could well be decided by how many young people register and vote for 8 June.

These findings – presented in the two analyses below – should inspire under-25s to realise how powerful they can be as a voter bloc. With the EU referendum fresh in minds and Brexit being a focal point, the 64% of 18-24 year olds who turned out to vote in the EU referendum should feel urged to vote again. After all, the quicker younger generations realise their power, the more likely their rights, opportunities and services can be saved.

Methodology.

Selecting which seats counted as marginal was based on the two reports from the Guardian and the UK Polling Report blog, and Electoral Commission data. 18-24 population estimates by constituency were calculated from ONS data.

Note these estimates are for mid-2015, so due to population growth, there may have been marginal changes in the numbers of 18-24 year olds now resident in these constituencies. Due to an overall increase in the national population, it may be assumed that the numbers of 18-24 year olds will have increased slightly on average. No more up-to-date data was available at the time of writing.

2015 turnout and other constituency statistics were taken from the Electoral Commission. The 18-24 proportion of that electorate was estimated by working out the proportion of all over-18 adults (using the ONS data linked above) who were in each constituency’s electorate, and applying that proportion to the ONS’s estimates of the total 18-24 year olds resident in each constituency in order to account for ineligibility due to nationality, etc.*

The potential electorate this time may have changed in size, and will be fluid with the voter registration window still open.

Analysis 1: Labour-held marginals and the 18-24 year old electorate.

The following is an analysis of 57 Labour-held marginals which will be targeted by the Conservatives in the 2017 general election. Looking at national polling, and the recent local election results, as things stand many of these seats are expected to turn blue in June.

However, in many of these constituencies, 18-24 year olds make up a significant percentage of the electorate, ranging from 7.7% in Wirral West to 26.2% in Coventry South.

Further, in constituencies with majorities of less than a hundred, literally every vote counts – so every additional vote cast by a young person could challenge expectations, specially as a recent survey shows university students are much more likely to vote for more progressive parties such as Labour, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats.

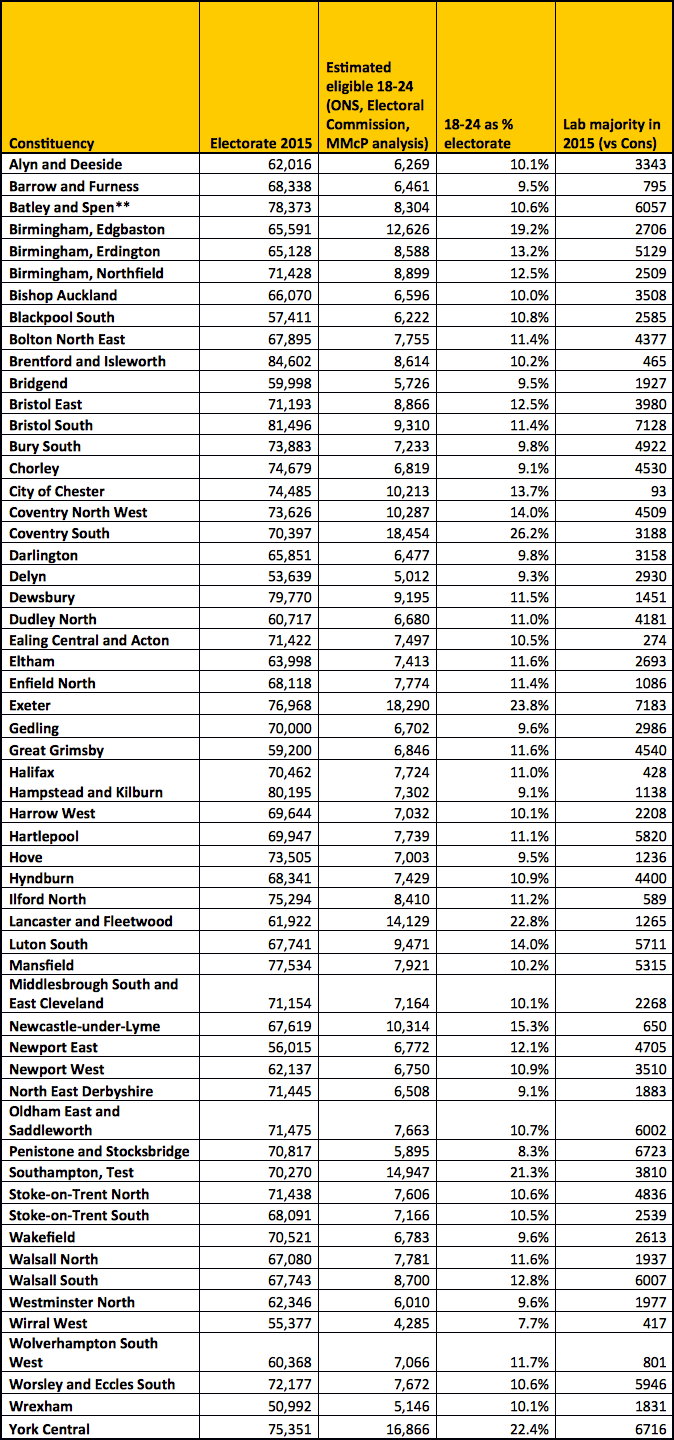

List of marginal seats (alphabetical order) along with estimated size of 18-24 electorate and 2015 Labour majority.

Not only do a number of these marginals have an 18-24 average population of 12%, but many also house universities. For example, York Central, Southampton (Test), Exeter, Lancaster and Coventry South contain universities within their constituencies.

Furthermore, as universities and student unions are likely to run voter registration drives, the under-25 voter turnout has the potential to be significantly higher in these marginals.

If campaigners are keen to mobilise under-25s to vote in order for votes to progressive parties to increase, it could be preferable to target marginals where universities do not exist. Some such marginals which could be targeted include Ilford North, Hyndburn and Dewsbury.

The scale of the threat of Ukip-to-Conservative switchers.

Without constituency-level polling, or party data on voter preferences, it’s not possible to look at the ramifications of Labour-to-Tory switches. Further, the possibility of progressive tactical voting is impossible to call on a constituency-level basis.

However, with the Conservatives framing the election around Brexit, and with recent national polls showing large falls in Ukip vote share (and a commensurate increase in the Conservative vote share) it appears that there is a very real threat in Labour-held seats of Labour majorities being overturned due to 2015 Ukip voters switching en masse to the Tories. The following analysis will therefore look at both the impact this could have, and how increased 18-24 voter participation could help Labour hold these seats.

In 52 of the 57 marginal seats, more voters voted for Ukip and the Conservatives combined than Labour in 2015.

If half of 2015’s Ukip voters switch to the Conservatives, and all vote shares stay the same across the rest of the parties, 29 of these 57 seats could turn blue in June.

18-24 year olds: How could increased participation make a difference?

According to the Ipsos Mori report ‘How Britain voted in 2015’, the turnout amongst 18-24 year olds in 2015 was 43%. The turnout across the whole population was 66% and amongst over-65s it was 78%.

It is not possible to know the breakdown of how 18-24 year olds voted in 2015 by constituency. However, it is possible to estimate the impact that the 18-24 year olds who did not vote in 2015 could have on the elections in these 57 seats if they were convinced to turn out in favour of a progressive candidate, all things being equal.

Scenario 1: If turnout increased to the level of over-65s.

In a situation where half of those who voted Ukip in 2015 were to switch to the Tories, 18-24 year olds turned out to the same level as over-65s, and all the previously non-voting 18-24 year old voters voted Labour, Labour would hold all 29 of the threatened marginal seats.

Looks good. But getting 18-24 year olds to turn out to the same level as over 65s – and all vote the same way – may be a bridge too far this time around. So what if they only turned out at the average (66%)?

Scenario 2: If turnout increased to the national average.

In the context of half of 2015’s Ukip voters switching to the Tories, of the 29 seats which would ordinarily be turned blue, 24 of them (83%) would be saved by the 18-24 turnout being just at the national average if previously non-voting 18-24 year olds voted Labour.

Of course, getting turnout up to the national average and translating all additional votes into Labour votes is not likely to happen as smoothly in practice. However, it is important to note that this analysis does not include tactical voting on the part of Liberal Democrat, Green and other pro-EU parties in the context of Brexit bloc voting.

Nor does it take into account the effects of increased participation from 25-34 year olds, another group which has lower-than-average turnout historically (54% in 2015 according to Ipsos), and which could also be mobilised by similar means as the 18-24 cohort. So the targets for a mobilisation campaign aimed at young people are potentially within closer reach than this analysis is assuming.

Scenario 3: 18-24 turnout increased to the national average and 75% of Ukip votes switch to Tories.

In the recent local elections, the Ukip vote dropped by more than half in some areas. Whilst local election results cannot be read directly across into general elections, the 2017 local election results would appear to be one of the best barometers of the forthcoming general election we have. Therefore, we ought to consider a scenario where 75% of Ukip voters switch to the Tories in June. This can be seen as a worst case scenario for defending Labour MPs, as it is fairly unlikely to happen – however it is possible, particularly if Ukip intentionally didn’t stand candidates.

In four areas, an increased progressive 18-24 turnout allied with those who voted Labour in 2015 sticking with the party, would be decisive in ensuring a Labour hold even in the face of such large scale switching: Lancaster and Fleetwood, Ealing Central and Acton, Blackpool South and Hove. These four seats should be prime targets for a mobilisation campaign.

Potential seats to target.

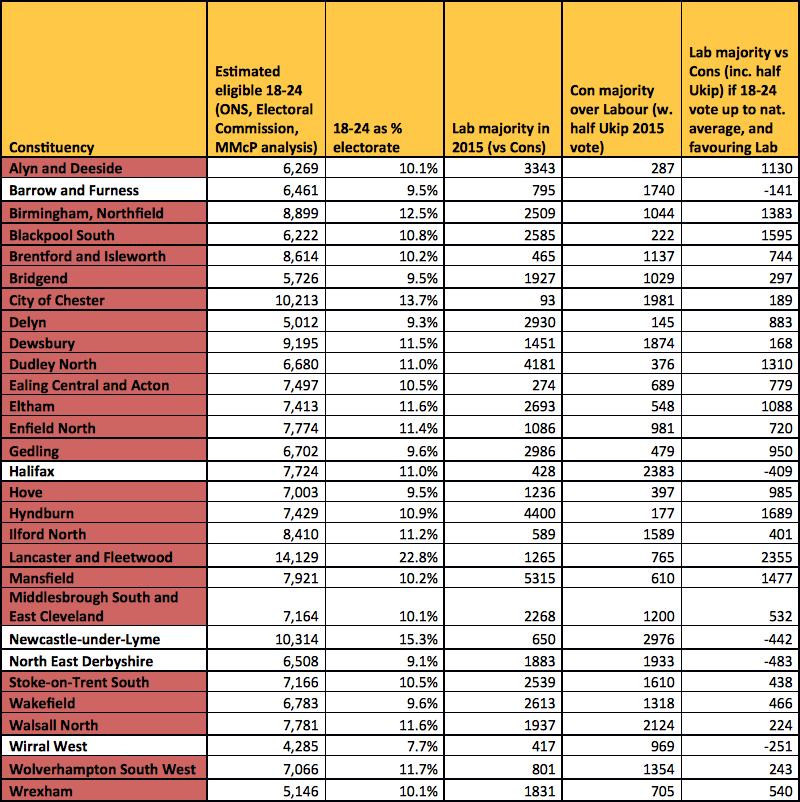

The 29 Labour constituencies which are under threat from half of the Ukip vote switching to the Tories can be found in the table below. Put simply, if the 18-24 turnout and Labour vote both stayed the same as in 2015, they would turn blue in June. The highlighted constituencies are those where increased progressive 18-24 participation would be decisive in holding the seat (although as stated, other switches and tactical voting have not been taken into account due to unavailability of data).

The fourth column shows the Tory lead over Labour if they receive half of the 2015 Ukip votes. Adding a negative sign in front of these figures gives the gap that Labour would need to make up with new voters in this scenario.

The final column shows the Labour majority if half of 2015 Ukip voters vote Conservative, and the 18-24 voters come out in larger numbers, with the additional 18-24 voters voting Labour. As can be seen, in many seats, increased 18-24 year old turnout could be decisive in securing a significant number of marginal holds for Labour in June.

Labour-held marginals are going to depend on a mobilisation of young voters.

The four seats where a mobilisation of 18-24 year old voters could enable Labour to withstand even a 75% Ukip-to-Tory switch should be targets – if Labour holds them in June it will likely be due to the young turnout. One of these seats, Lancaster and Fleetwood, includes a university population. Labour-held marginals are going to depend on a mobilisation of young voters.

National polling and the recent local election results suggest it will be challenging for Labour to hold many of these marginal seats – the large-scale switching from Ukip to Tories being the primary danger.

Tactical voting will have to play a part in Labour holding many of these seats (which this analysis has not incorporated). However, it is estimated that in around 24 of the 57 marginals examined, Labour will need an increased 18-24 mobilisation to hold the seats if around half of 2015’s Ukip voters switch to the Conservatives. If Labour can hold position and get the progressive youth turnout up to the national average, it will hold 32 of these 57 Labour marginals even in face of 75% of Ukip voters turning Tory.

Analysis 2: Conservative-held marginals and the 18-24 year old electorate.

35 Conservative seats are designated as marginal – all those which were held by a majority of around 2,000 or less in 2015 according to Electoral Commission data, plus a number of key Liberal Democrat targets, frequently in the south west.

27 of these 35 marginal seats are estimated to have voted to Leave in the EU referendum. Exact figures at constituency level are not available for the majority of constituencies, as the EU referendum was not conducted by parliamentary constituency. However, Chris Hanretty of the University of East Anglia has estimated the Leave and Remain vote shares, which have been added to where possible by actual vote shares in situations where ward geographies map onto constituency geographies.

In practice, as demonstrated by the Conservatives’ recent showing in the local elections, many of these seats will not actually be marginal, with the Conservatives looking on course to receive half or more of the previous Ukip vote in many areas. As we have seen, the factoring in of this Ukip-to-Tory swing is a key element of the analysis on Labour-held marginals.

It should be said that the following analysis does not account for Labour-to-Conservative switches, as it is not possible to do so with the available evidence – instead it is assumed that Labour is on course to maintain its vote from 2015. Whilst this may be optimistic in some areas, national polling since the announcement of the general election and local election results indicates Labour will tend to be in the same ballpark. If Labour-to-Tory switches should happen at scale, the whole rationale for this analysis is null and void anyway, so for now this is a necessary assumption to make.

Size of 18-24 electorate and non-voting 18-24 year olds in 2015.

18-24 year old electorate estimates in the following analysis were reached by the same process as the estimates in the above analysis for Labour-held marginals. Turnouts for each constituency were calculated from Electoral Commission data.

There was no age-breakdown of turnout by constituency, but as we know from the ‘How Britain Voted in 2015’ report, the 18-24 turnout was 43%. In order to estimate the 18-24 turnout in 2015, and therefore the number of eligible non-voters, it was assumed that 18-24 year olds turned out as a fixed proportion of average turnout in each seat (e.g. 65% of the average for all ages, as was the case nationally). This is an assumption and will not be correct for each seat – however, this estimate is unbiased, and therefore the number of non-voters is as likely to be higher as it is to be lower than the point estimates included.

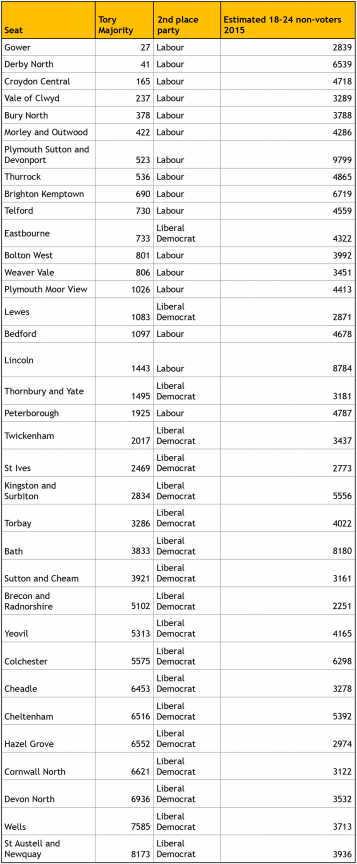

List of 35 marginal seats (by size of majority) along with estimated number of non-voting 18-24 year olds in 2015.

As can be seen in the table above, in 25 of these seats there are estimated to have been more 18-24 year old non-voters than the Tory majority. However, 100% turnout is an unrealistic assumption, particularly with the age group which has historically had the lowest turnout.

Therefore in the table below we examine the impact if the youth turnout is 66.3%, the same as the national average in 2015. The rows which are highlighted indicate rows where this additional turnout would be higher than the current Tory majority, with the colour indicating the victorious party in these hypothetical situations, should young people vote tactically.

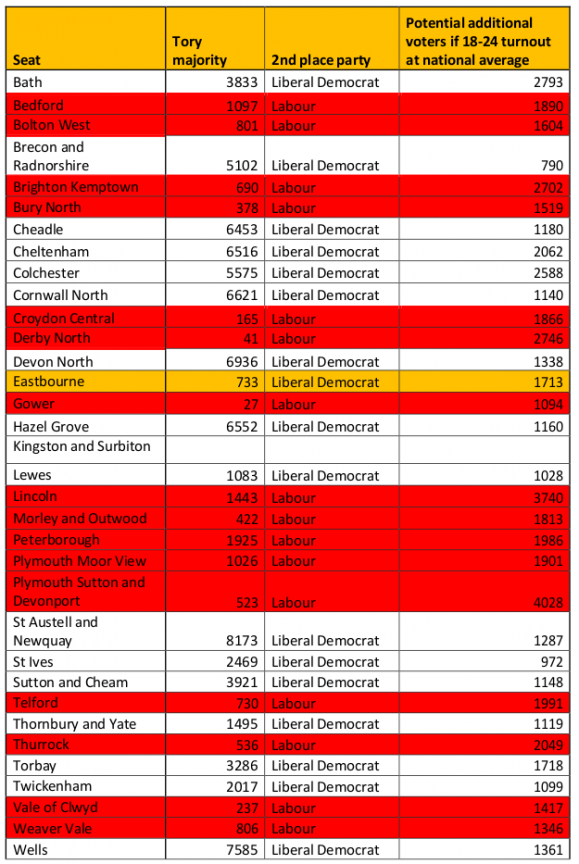

List of 35 marginal seats (ordered alphabetically) along with estimated number of additional voters if 18-24 year olds turn out in line with national average.

These are very interesting findings, with 16 seats where Labour in second place and one seat where the Liberal Democrats sit in second place seeing the potential 18-24 progressive vote outweighing the current Conservative majority.

However, it is very important to note that a large number of these 17 seats also witnessed thousands of Ukip votes in 2015 – therefore given the recent local elections which saw wholesale shifts of previous Ukip votes to the Conservatives, it is very probable that many of these seats are a lot further out of reach than expected – and therefore those with very small majorities in 2015 have to be prioritised (such as Gower, Derby North and Vale of Clwyd).

Of course, not all non-voting 18-24 year olds will have a desire to vote for a progressive party, so getting the increase in turnout to exclusively benefit progressive parties will not happen as smoothly in practice. But more positively, it is clear that 18-24 year olds are both more likely than average to have supported Remain, and also to support parties such as Labour. Furthermore, according to some accounts their turnout did actually approach the national average in the EU referendum.

Therefore mobilising the 18-24 year olds who didn’t turn out in 2015, but did vote in the EU referendum, to vote against the incumbent Conservative candidate is one of the only possible ways that a Ukip-bolstered Conservative vote will be overcome in these seats.

The seats where the Leave vote was less strong.

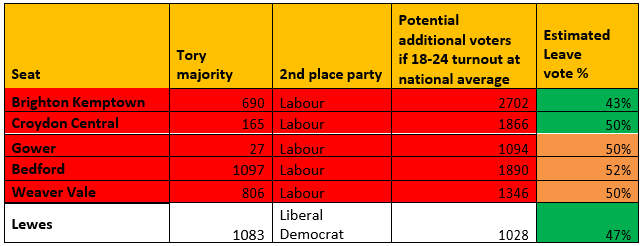

The Conservatives intend to make this election about Brexit primarily. Therefore, it is interesting to look at the constituencies where this message is less likely to cut through. Looking at only those constituencies where 52% or under voted to Leave the EU, the six seats where a mobilised 18-24 vote does the most damage to the Tory majority are can be seen below.

NB: The Leave vote for Croydon Central and Bedford are actual figures calculated from ward level data, and therefore are presumed to be more accurate.

Two seats in particular stand out as healthy ground for such a mobilisation: Brighton Kemptown and Croydon Central, which are estimated to hold as many Remain voters as Leave voters. Further, whilst the Tories would hold on in face of greater mobilisation of progressive 18-24 year olds in Lewes, the higher Remain vote and the history of the seat being held by the Liberal Democrats, means that in practice the target may closer within reach.

Resistant Tory majorities and the Liberal Democrat effect.

Looking at the 18 seats where the 2015 Conservative majority alone, all things being equal, would still be resistant to a mobilisation of progressive 18-24 year olds – it is interesting to note all of these seats were held by the Liberal Democrats in the 2010-2015 parliament. On the back of the EU referendum the Lib Dems have positioned themselves as the party of Remain, and national opinion polls have shown a modest increase in the Liberal Democrats’ vote share. This might lead us to hypothesise that the gap to be made up in these seats by a mobilised progressive youth vote could be smaller than estimated.

However, the recent local council elections appear to tell a different story – with the Liberal Democrats making little ground in many of these areas. Whilst not proven, this suggests the legacy of Liberal Democrat involvement will struggle to outweigh positioning on the referendum which is in contrary to the majority of these areas’ constituents. The legacy of Lib Dem control therefore may only be a positive factor in areas which are also ‘Remain-friendly’.

Bath (2,793 additional voters if 18-24 vote at 2015 national average of 66%), Cheltenham (2,060), and Kingston and Surbiton (1,980) all are expected to be home to high levels of Remain voters. They would appear to be some of the reasonable targets for a finite campaign to focus on.

However, again it is worth mentioning that for such a mobilisation effort to bear fruit, it will rely on an above-average swing from the Conservatives to the Liberal Democrats.

Recommended seats to target.

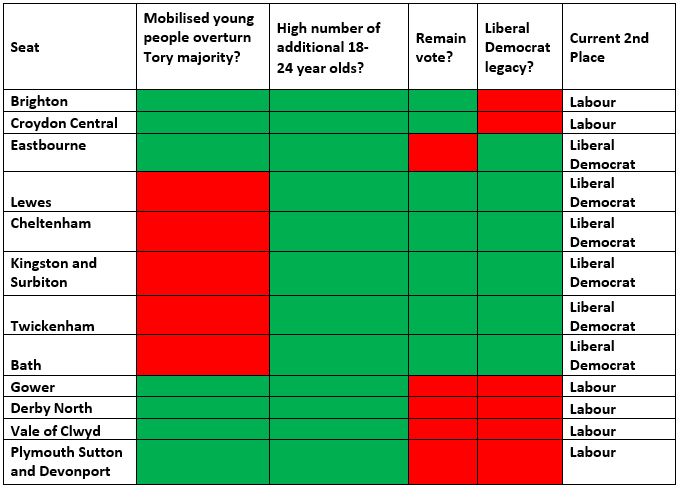

The table below provides a matrix of 12 of the marginal seats held by the Conservatives which this analysis suggests are most susceptible to a youth mobilisation campaign. The seats are listed in order of what we believe to be the seats most likely to change hands on the basis of this multivariate analysis. As can be seen, eight of the seats match three of the desirable insight criteria, and would appear to be priority constituencies for a mobilisation campaign, particularly the top four.

An additional three (Gower, Derby North, Vale of Clwyd) are all held currently with majorities of fewer than 300, so may be worthwhile secondary targets for a larger scale campaign. However, all saw Ukip in third place in 2015, with over 4,000 votes – so in practice these targets may be a struggle to reach.

Finally, Plymouth Sutton and Devonport is included – as it was the marginal seat which is estimated to hold the highest potential number of additional 18-24 year old voters. In this seat even with the Tories and Ukip combined, this additional progressive youth vote would win out. A big reach, but one to consider.

Tories losses will be hard to manage.

In conclusion, the national polling and the local election results demonstrate that in practice, taking seats off the Conservatives in more than a handful of seats will be very difficult. Whilst the Liberal Democrats are seeing a modest national revival, the geographical areas where they are picking up votes are urban areas where they are third behind Labour. Unless there is a significant change in the landscape, they are not going to be able to eat into many healthy Tory majorities in the south west. Therefore, in terms of maximising potential wins, an ‘attack’ youth mobilisation campaign should be more focused on a handful of seats as outline above.

However, this analysis concludes that the 12 seats above are ones where an increased 18-24 vote (benefiting progressive parties) may prove decisive – without it, there is little evidence that the Conservatives will relinquish control of more than a couple of seats in June.

–

*With migrants more likely to be of working age on average, this may lead to the 18-24 group marginally reducing as a proportion of constituencies’ electorates. However, with the majority of the analysed seats experiencing low levels of immigration, this is not expected to change the results substantively.

**There was a 2016 by-election in Batley and Spen – however, the Conservatives (and other parties) did not stand a candidate due to the murder of Jo Cox. The 2015 result is therefore used as a barometer.