“If our people are instructed that political action cannot produce economic results, then again, as Nye Bevan taught us, the consequences for our democratic political institutions will be immeasurable.”

“That is why we say, and I repeat it again and again: only in the hands of democratic Socialism, radically and audaciously applied, can democracy itself be truly safe in the end.”

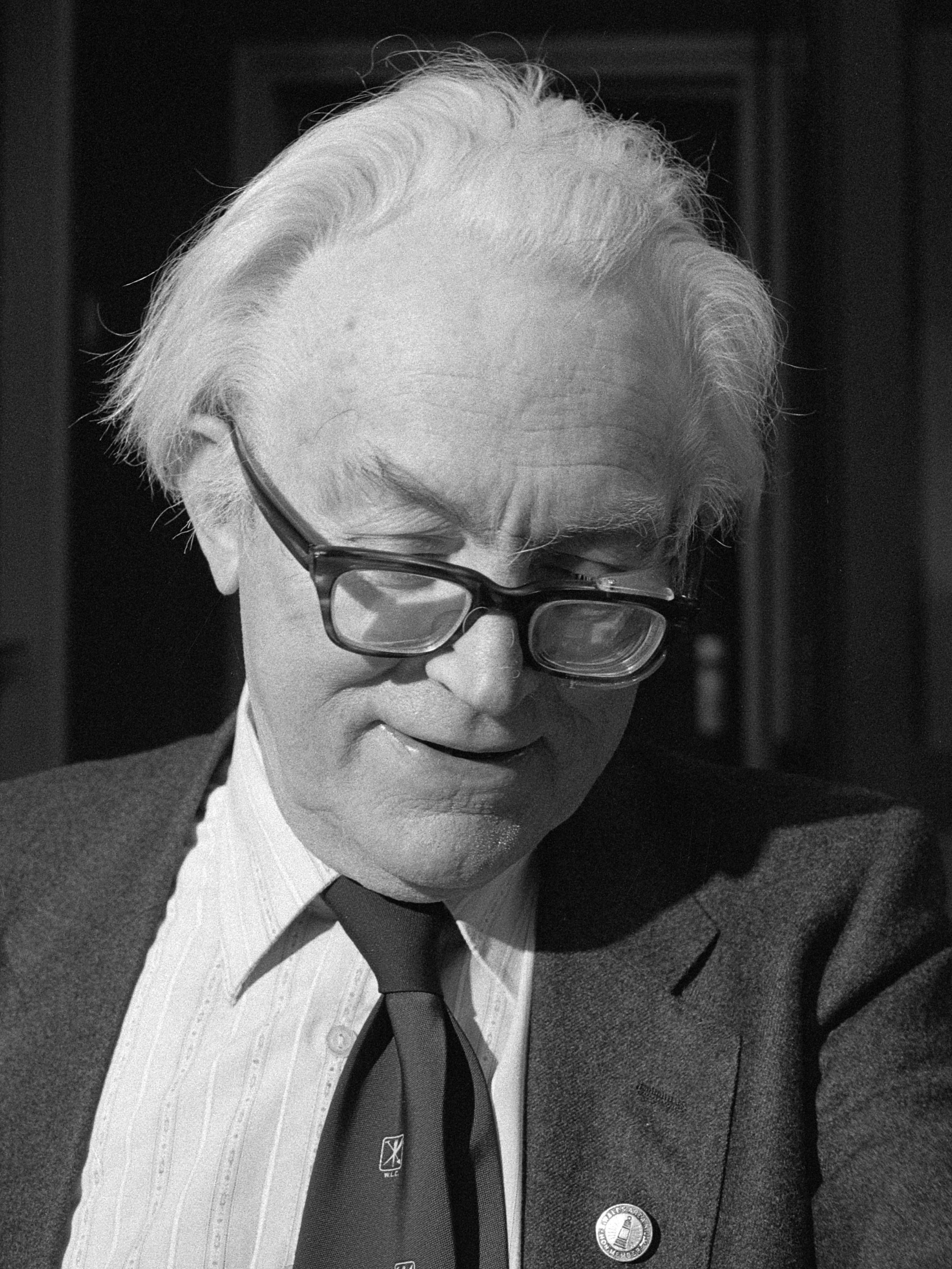

This was Michael Foot’s warning on his last stop in the final week of the 1983 General Election campaign, made to a rally at the leisure centre in his constituency, Ebbw Vale.

27 years of neoliberal consensus and one immeasurably destructive referendum later, he and Bevan, another Ebbw Vale MP, seem to have been vindicated.

It is the only full speech Foot quotes in his memoir of 1983, Another Heart and Other Pulses, which I read recently as a mental salve to Labour’s troubling polling figures and internal disputes. Now, the party goes to the polls again with a leader from its left.

According to Foot his book was meant neither as “a diary or a batch of memoirs or a polemic or a personal apologia,” but in effect it is something of all three.

He was dismayed by the collapse of the Labour vote: his belief, that a re-assertion of the post-Fordian settlement, with full employment, renewed public ownership and a reinforced welfare state, would reverse Labour’s fortunes turned out to be utterly wrong.

Another Heart seems his attempt to grapple with why and how such a loss came about, and an apology. Many in the ‘new left’ tradition of Labour now take Foot’s vision – of not just continuing but celebrating the 1945 consensus – as the ultimate reason for his loss. They believe he failed to present a suitably transformative vision of the Party and the state.

But it’s important to remember, considering much of the left has now become so invested in Labour’s fortunes, that there are structural problems with British political democracy which contributed significantly in 1983, and cannot be forgotten for their relevance today.

Foot faced a coalition of liberal and conservative interests in 1983, including a literal alliance of the Liberal and SDP parties, which many would recognise as facing Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour today.

It was the first election, for example, where regular polling consistently predicted only one winner, Margaret Thatcher, as Foot’s poor personal rating as leader was stated again and again – to his dismay – distracting from substantive discussion of policy.

“A man’s character and intelligence – even a politician’s – are matters of infinite complexity,” he wrote in a letter to The Times in 1969, republished in the book. “The English language is the best instrument for gauging these shades and nuances, and was partly designed for the purpose.”

The 1983 polls, combined with briefing from parts of the Labour Party, put pressure on him to resign and make way for his deputy, Denis Healey. He refused on the basis the press would claim victory, and Labour would be thrown into a factional war which could be impossible to reconcile before the election.

In fact in the week before the election the Daily Express did publish an article claiming Foot had stepped aside for Healey, which was untrue but contributed to a sense of chaos in the opposition party.

Both tabloids and broadsheets ran inflated stories of the potential success of the Liberal-SDP alliance, strongly persuaded by spinners in the respective parties, giving the splitters, led by David Owen, disproportionate exposure.

“Most of the newspapers were much more interested in presenting their own case than to report what was being said at public meetings and on the doorsteps,” Foot wrote. “Many of the television and radio programmes merely reflected what they read about in those same newspapers.”

In another incident, a reporter for the Express followed the party’s People’s March for Jobs, offering lists of vacancies from local jobcentres to the protesters, accusing them of hypocrisy and being work shy when they refused.

So bad was the intense bias at the Daily Mail, Foot notes, that in 1983 50 of the paper’s staff convened a meeting to demand senior staff give more space and a fairer degree of prominence to parties other that the Conservatives. Their mini-revolt was crushed.

Worst of all for him though were interventions by former party leaders Jim Callaghan and Harold Wilson.

Two weeks before the election Callaghan gave a speech joining in Michael Heseltine’s attack on Labour over their then commitment to unilateral disarmament. Worse, he proclaimed his faith in Thatcher and Reagan’s multilateral disarmament talks in Geneva.

Harold Wilson then gave an interview to the Daily Mail: “WHERE MY PARTY HAS GONE WRONG.” He accused Foot of being too close to militant, and gallingly said he had not focused sufficiently on employment, the issue that Foot had made the centrepiece of Labour’s campaign.

Despite all this, Foot considered himself personally responsible for the defeat, and knew the damage Thatcherism would do. Unlike many of his contemporaries by 1983, his political education was Neville Chamberlain’s austerity in 1930s Liverpool:

“I saw in the back streets – or along the road where I walked to Goodison Park every other Saturday – the wreckage left behind by the unplanned, inhuman industrial revolution: the revolution made not for man or woman, but for machines and private profit.”

Corbyn and Foot come from different Labour traditions: for Corbyn, Labour is a temporal but necessary vehicle for left-wing change. For Foot, it was a sacred bond between parliamentarians and the Labour movement, and his deepest fear was the party’s collapse.

The lessons of that election should not be ignored. The demands in Labour’s manifesto then were similar or even stronger than the party’s promises today, and it is incumbent on Corbyn to cut through where Foot could not.

The polls are picking up, but started below even where they were under Thatcher. It took the Labour Party fourteen years to recover from the defeat of 1983, and arguably the left even longer.

Our hope now must be that both are more successful – and resilient – than they were.

“Sometimes we suffer setbacks, but we don’t let them defeat us,” Foot told Ebbw Vale. “We certainly are not going to be wheedled out of our rights or threatened out of those rights.”

“We demand for these valley towns, as we demand for our country as a whole, the mobilization of the power of the community, the investment of the community.”

“That is that only kind of policy to save us here, and the only kind of audacious policy that can save our country too.”