Debt, Markets and Pepe: The Reactionary Face of LSE’s Student Body

by Joe Hayns

5 June 2017

Thursday 25 May, the third day of United Voices of the World (UVW) cleaners’ indefinite strike at the LSE, and another student walked away from the picket, over acting their disdain: a shaking head, a scowl back.

UVW began organising on LSE campus after three cleaners were suspended by their subcontracted employer, Noonan. Unison did nothing; cleaners heard that UVW was a better gig. Within days of the first call, all three were reinstated.

In December 2016, UVW cleaners initiated a formal dispute with Noonan, demanding parity of terms and conditions (sick, holiday, and maternity/paternity pay) with in house workers. With those demands rejected by LSE management and Noonan, UVW cleaners struck in mid March. After a derisory offer – ‘a slap in the face’, as one cleaner said – UVW cleaners decided to initiate an indefinite strike, which began on 11 May.

That IWGB security officers and UVW cleaners coordinated their 17 May strikes was a sign of growing power, their traffic stopping march together risky. Soon after that, SOAS Students Union announced their solidarity with both struggles. And, last Saturday the left faction of UCU, the college and university teachers’ union, spoke with UVW cleaners via Skype from their Brighton conference. The first time UCU have made any collective gesture of solidarity; from LSE UCU, there’s still silence, shamefully. Solidarity is moving from the individual to the institutional level, then.

Given this, and with the purposefully loud strikes presumably audible from the LSE students’ union office, it’s strange the campus union has said nothing, so far, about the strikes or UVW. Why?

LSE students

The two minorities – one a self conscious collective actively for the strike, the other actively against, as individuals – have changed little in either size or attitude since December. The former group, even in times and places of rightward drift, will be there on campus: one student, hostile to the strike, said that ‘it’s about 10% of students, you can point them out, that are actively engaged in these campaigns and really involved; they’ll be the ones pursuing these agendas’.

The existence of the other minority – ‘if they [the cleaners] don’t want the job, they shouldn’t sign the contract’, as one student said, his friend nodding – is probably even more dependable, especially in institutions where, across most courses most of the time, marketable grades depend on at least the perfunctory repetition of (something like) social sadism. It’s the changeable, changed majority that are the most curious.

Campus based cleaners’ campaigns tend to be popular amongst university students: ‘3 Cosas’ at the University of London, the cleaners’ pop up union at Sussex University, and even UVW at LSE, until recently, had the tacit support of the majority. Of course some students are too hip, or high, or studious, to be politically active. What’s new is the resting reactionary face of the majority.

The fact that UVW cleaners are all workers of colour, that most are women, and many are into their 50s and 60s makes them all the more ‘sympathetic’ to even not-such-bleeding-heart liberals. One trade union officer and militant – not UVW – stated the obvious when they said, off the record, that ‘students fetishise cleaners’; not many LSE students now, though.

As management knew, the mid March ‘slap’ meant either UVW and the cleaners effectively kill the campaign through delay until September (six more months without the demanded sick pay, etc.) or continue into the exam period.e

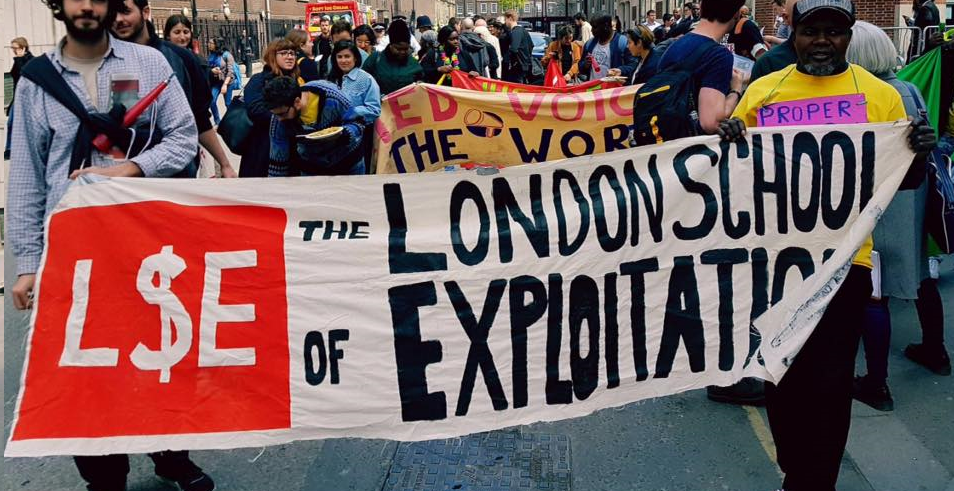

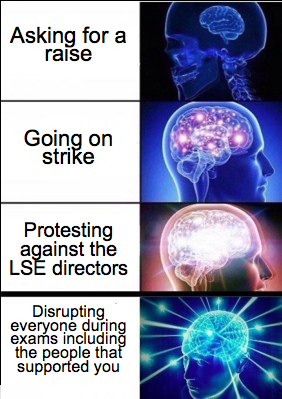

Below is a meme made on the ‘Robust Memes for LSE teens’ on the morning of the first strike of the indefinite phase of the campaign, note the Pepe in the crest:

Introduced with the line ‘Congratulations Justice for LSE Cleaners… you played yourself’, with 350 positive ‘reactions’, the meme was about as popular as the page’s usual bullshit (complaints about teaching & microeconomics bantz).

One student explained that the ‘passive majority have turned against this type of activism’ at the end of day rally; earlier, another complained that cleaners ‘have camped [picketed] outside the library multiple days now’:

“A lot of the student body were supporting them, there were campaigns, petitions were signed, I was part of it. I signed the petition for them to get equal rights and sick pay, for whatever they’re after, and everyone was behind them, and now they’ve used students as pawns basically to get what they want.”

As a description of the changing relationship of the majority of students to cleaners, this is about right. But, as a demonstration of what’s become ‘instinctive’ for many at LSE, it’s even better.

Notice, it’s the cleaners that are ‘using students as pawns’ against management, not vice versa, and that it’s cleaners who are trying ‘get what they want’, not Noonan. The cleaners are the active group, and their activity is both antisocial (‘fundamentally wrong’, in the same interviewee’s view), and peculiarly materialistic. The motivations and forces of the LSE management and Noonan are absent from the story: the cleaners are to blame for disruptions and for the dispute, and them only. The idea that striking workers are ‘playing themselves’ presumably easily comes to mind to right wing meme makers, but it’s also indicative of a student body that doesn’t really understand either ‘Economics’ or ‘Political Science’ (and much less the two together).

As one UVW officer said earlier in the month, students need to realise that it’s Noonan and the LSE that are using them as leverage, not the cleaners. They need to realise that:

“If they’d [management] given a shit, they could have predicted this would happen; if they’d given a shit, they would have tried to avoid it. If they gave a shit about the students, if they’d given a shit about anything, except money and prestige, then this wouldn’t have happened in the first place.”

Why haven’t they?

Debt and exams

In the post war period, responding to the changing demands of capital, state run universities across the core imperial countries shifted from being prep schools exclusively for politicians and magnates, to places where the broad working class – typically but not only the better off strata – were also trained for the white collar and skilled blue collar worlds.

In France in the years immediately prior to WWII there were roughly 60,000 students at any time; twenty-or-so years later, there were nearly ten times as many, with 500,000 by May 1968. In the UK, ‘overall participation in higher education increased from 3.4% in 1950, to 8.4% in 1970, 19.3% in 1990 and 33% in 2000’.

Before the era of debt, and the massive increase of rents in the UK – students are paying more for halls than their parents for mortgages – tertiary students on average worked for money far less. Temporarily outside the labour regime, and in institutions that taught the ‘critical ideas’ necessary to some sectors (the media, the arts, education) people studying in universities were ‘very sensitive to elements of social crisis in society as a whole’, with protests ‘suddenly erupting in an explosive fashion’, as Chris Harman wrote.

Anyone involved in the student protests against increased fees and cuts to universities in 2011 and 2012 will recognise this explosiveness. But, since even then, the experiences of higher education in the UK have changed dramatically, even qualitatively.

University life was never ‘outside’ of market calculations, but calculations were made only more personal after the 2011 Education Act (the average student will pay almost £60,000 for their education). Even the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) knows that increasing students’ fees and debts was little to do with ‘saving taxpayers’ money’. Governments borrow the money to lend to students, but not all students will pay off their debts, which are annulled after 30 years: ‘The net effect on the public finances is primarily an increase in uncertainty’, as an IFS analyst said. Still, the 2011 Act worked.

Last summer, whilst UCU picketed outside a University of Central London library, activists again and again heard variations on the line, ‘I pay £9000 per year to use this library’ (the pronoun the most telling word, of course).

The ideological force of debt has conspired with cuts to university budgets – especially to social science and humanities departments –to make learning feel both more rarefied and more ‘mine’.

Borrowing money to pay for education in order to get a better job is about as literal a ‘self investment’ as we can make. On being asked if they appreciated the optics of LSE students being against the people who clean their toilets getting better sick pay, one student said, ‘in the long run these exams are going to dictate your future, dictate your job, dictate a lot about your life, and these are temporary protests.’ So much for students?

Endgame?

‘The first thing to understand about colleges and universities is that they are workplaces’, Michael Yates wrote recently. And, as at most workplaces, strikes on campus are now against the grain of how most workers on tend to live, and how institutions tend to function.

They’re strange and accosting experiences, with the back and forth of industrial action not only over wages and profit, but also ‘common sense’: words’ consequences increase, and otherwise banal actions – a Unison rep’s standing with management, opposite a picket – are understood better; security officers at the UoL went from policing cleaners’ strikes to co-ordinating work stoppages with them.

They are times when arguments for ‘normality’ are repeated, much louder than usual, probably first from individuals ideologically committed against struggles likes the cleaners’. One student explained his opposition this way:

They [the cleaners] signed the contract. They knew the terms and conditions when they signed the contract. I don’t understand. They have to fulfil their contract. They could leave and find another job.

That minority view has become less minor over the course of the UVW strikes, and may come to dominate amongst students.

As Callum Cant wrote last year, with levels of debt, rents, and work all at record levels, ‘students now relate to education as a strange combination between a consumer good and a program of intensive job trainings’. There is much to this. But, neither debt nor overwork nor, most obviously, waged labour have necessary political expressions; indebtedness has produced subservience at the LSE, and presumably far beyond, but it can – may still – produce the opposite, if individual repayment anxieties are remade into collective opposition to student debt per se.

This requires organisation. But, students’ unions, at least in London, seem to be barely functioning as oppositional efforts. LSE SU have been more responsive to journalists than UVW or the solidarity campaign, but their sabbaticals have just seemed too boring and too ambitious to be worth interviewing; besides, with exams over by mid June, the opportunity for the current LSE sabbs to positively affect the campaign is gone, it seems.

Pro Palestine activism has continued on campuses since 2011, and the anti sexual violence, anti hate speech, and decolonisation tendencies since then have all produced a new generation of anti-oppression activists.

But in terms of labour disputes – which are never only about class, of course – it’s only the more democratic, more militant trade unions representing precarious workers – IWGB, UVW, and para-union groups like the SOAS Fractionals For Fair Play (FFFP) – that have worked at all effectively on campuses since 2011.

Students have never been more indebted, never worked more, and are paying through the roof housing costs, whilst studying at universities increasingly staffed by indebted, overworked graduate teaching assistants. Realising that these circumstances tend towards apathy and even reaction amongst students is not new (see here for a critical report on the 2015 occupation at LSE); what is different now, though, is that militant trade unionism is returning to campuses, albeit ones more hostile than possibly ever before.