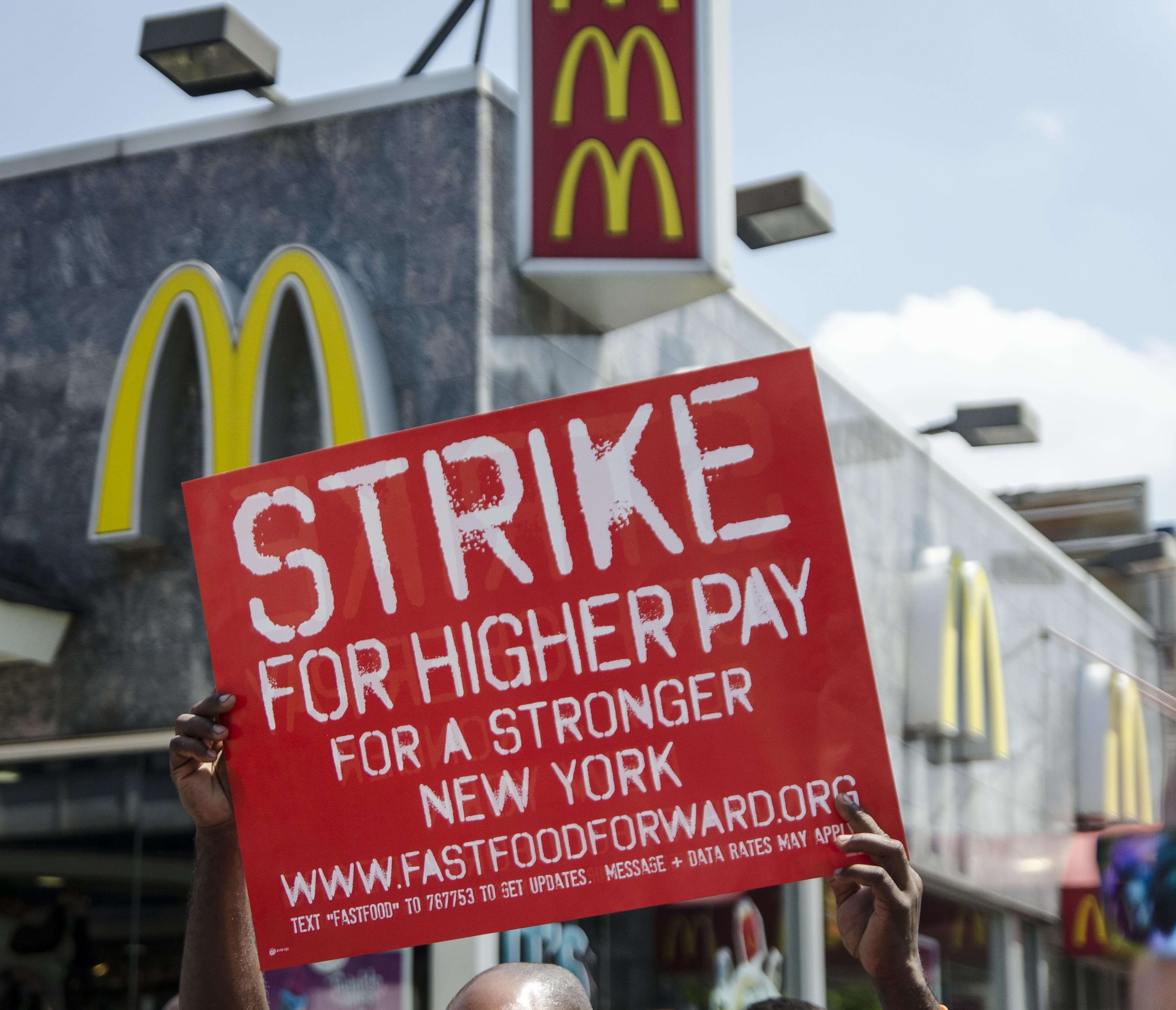

Earlier this year, a group of McDonald’s workers went to the Bakers, Food and Allied Workers Union (BFAWU) with complaints about anti-unionisation bullying, exploitative contracts and low pay. The union balloted members in the Crayford (south east London) and Cambridge stores. In late July, the vote came back, with workers near-unanimously in favour of strike action.

The anti-union machine powered up fast – employees were invited to start taking food home, managers started smiling. But in spite of this, workers will strike at both branches on Monday 4 September. It’ll be the first work stoppage at McDonald’s in the UK since the first branch opened in Woolwich in 1974.

It’s not just trade unions either. In January 2016, John McDonnell hosted a delegation of Fight for $15 activists to discuss their international campaign against low pay, long hours and working conditions in fast food restaurants. In the spring, Jeremy Corbyn backed the National Executive Committee’s banning of McDonald’s from Labour’s annual conference. It cost the party £30,000, but at least The Guardian and Wes Streeting hated it.

Are McDonald’s and other employers in the service sector in trouble? We spoke with National President of BFAWU Ian Hodson about where the strike came from and where it might go.

During the so-called McLibel trial in the 1990s, in which McDonald’s took two activists to court for defamation, the judge said in his verdict that McDonald’s were “strongly antipathetic to any idea of unionisation of crew in their restaurants”. Hiring new workers, firing trade unionists and “odd challenges from expensive lawyers” were, at least, fairly routine anti-union tactics. Has anything changed since then?

McDonald’s haven’t changed in their approach to unions. Workers still face risks if they join, as this dispute has proved. When a manager found that some workers had joined the BFAWU, they cut the workers’ hours. When workers said they intended to bring the union in to represent them, the company suggested alternatives. We’re also aware they’ve offered money to workers to join the union so they can report back on what’s being said. McDonald’s say one thing in public and act differently in reality.

Only this year we’ve seen the United Voices of the World cleaners winning at the London School of Economics, the Independent Workers of Great Britain security officers taking serious action at the University of London and more recently Unite cleaners stopping work at St. Bart’s. There seems to be a trend towards workers in the service sector taking offensive industrial action against employers – why now? Can we expect more?

I think people are fed up with being treated so poorly by employers. The fact is that for so long people have been told they have to just get on with it, that they can’t do anything about it. But with each victory, with each fight, workers are recognising that life doesn’t have to be so bad.

Younger workers have little to lose. They’re discriminated against, have lost their long-term benefits, have been hit with student fees. Most won’t get a contract, so are unable to plan their lives, so I think they’ve thought “I’m not having this”. I think workers are now open to working collectively.

I think this is the start of workers taking more control over their lives. I think more will organise and take action.

McDonald’s relies on lots people feeling more-or-less OK about eating there – they’re vulnerable to shaming. Is this is an opportunity for trade unions, who can mobilise consumers against the firm, through protests, street parties, media campaigns? Theresa May’s Trade Union Act (2016) has made organising strikes much harder, at least for essential public service workers, whose unions need to get at least 40% “yes” to strike. Notice periods went up, and unions need to re-ballot their members sooner. Is there a case for focusing less on stopping production, than stopping consumption?

We’ve avoided calling for boycotts since they can be used by employers to claim we are putting employment at risk. We’ve seen companies like Samworth Brothers using that counter-tactic quite effectively. We think that highlighting the impact of how contracts and pay affects the lives of the workers is a far more powerful way of connecting to the community. It also keeps the moral high ground, which is important for the morale of workers and for keeping the public on side. Close contact with the union and setting tasks for workers has delivered before in these types of workplaces, for us anyway. Victories encourage workers, not boycotts.

You’ve been working closely with the Fight for $15 campaign, which was started in 2012 by the US-based Services Employees International Union (SEIU). It’s a big reason why state legislatures across the US are passing phased-in $15 per hour laws. Employers and their political representatives hate it, but there’s criticism from the left, too. The prominent organiser Jane McAlevey said: “The problem is that there isn’t any depth to the Fight for 15 campaign”; too much media, not enough organising in the workplace. That doesn’t seem the case at all with BFAWU – is McAlevey way off?

Yes, I would say way off the mark. You can’t rely on how we would normally organise in these workplaces. Most people in them have never been in, or involved in, unions and their opinions are based on how we are portrayed in the media. Objectives like the call to end lower minimum wages for younger people, to end zero-hours contracts and to increase pay mean they can see something that makes improvements to their lives.

Any preconceived ideas about what unions are or do are removed. Asking someone what £10 means to them and how it would improve their life is different to asking “are you aware of the benefits unions offer?” It’s more relevant and the end result is to organise workers to help improve working conditions and pay. This is different to the traditional way that unions have organised; personal contact is critical.

And with respect to the Fight for 15 campaign, meeting many of the workers in the US it is clear they are keen to organise and become part of the union. I would say yes, it’s different, but it’s definitely about unionisation.

People are excited about the strike partly because, despite some strong efforts, the service sector is desperate for organisation. This is one reason people are so up for BFAWU’s strike. But it’s also because McDonald’s is a globally-recognised firm, and it’s much easier to imagine an international strike against it. Are there any dangers of organising internationally against one firm, rather than sectorally on a national basis?

This is a new venture for us as a union. We’ve always supported unions around the globe, but this is the first time we’ve worked with others to unionise. There are risks associated with any campaign, but there are also benefits too. Our relationship with Unite New Zealand, for example, demonstrates that we can win recognition and improvements for the workers together.

When a McDonald’s worker joins the BFAWU in the UK they are part of a union family that now includes McDonald’s workers across the globe. Our recent victory in the EU over McDonald’s use of zero-hours contract was due to ourselves, the European unions, and the SEIU working together to ensure we could properly argue against McDonald’s and its working practices.

Solidarity has always been how workers have won. Whether it’s here in the UK or international, it makes our campaign stronger.

How can we support you on the day?

There are different ways people can support the strike. We’re organising a demo outside McDonald’s HQ in Finchley on Saturday 2 September. Supporters can donate to the strike fund.

On the day of the strike, on 4 September, the Cambridge picket will be between 6 – 7am, and at Crayford between 6 – 7.30am. That same day Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell will be speaking at our rally outside parliament in support of the strike, between 10.30-11am. We want as many people as possible to come to that.

Nice one, thanks Ian. Solidarity.