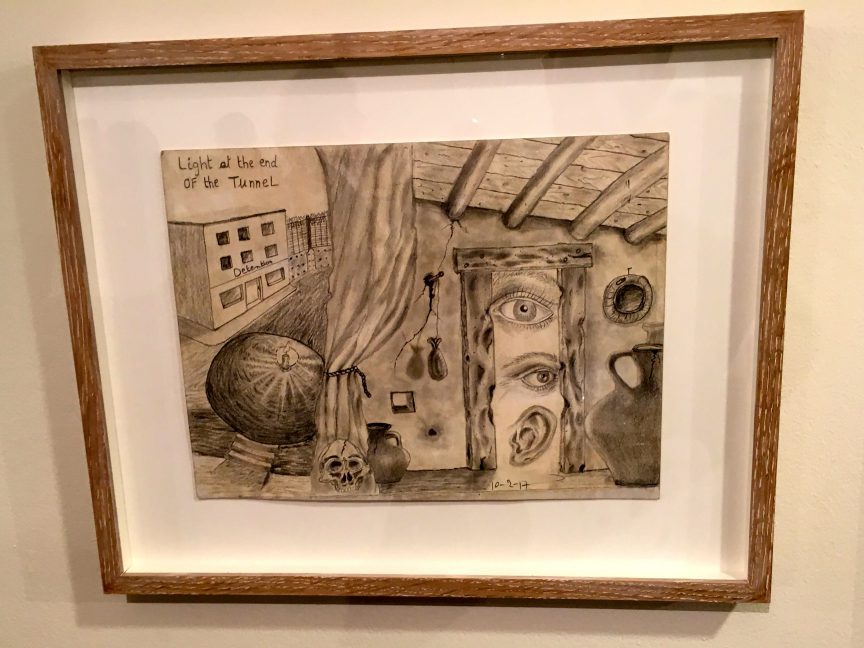

A drawing on the wall shows a dilapidated room. Giant eyes and ears block the exit, and a skull sits in the corner, beside a threadbare punchbag. Outside the artist has depicted a yard, a building marked ‘detention centre’ and a perimeter fence. Above this fence words in the sky spell out: “The light at the end of the tunnel.”

The picture is called ‘hope’ and the artist, Mohammed, is a man currently detained at the infamous G4S-run Brook House Immigration Removal Centre. Secret filming recorded in September as part of a Panorama investigation showed staff mocking, abusing and assaulting detainees in the facility.

Just yards from where Mohammed’s artwork hangs on the wall, G4S’s UK and Ireland boss Peter Neden is chatting to three other smartly-dressed middle-aged men, all drinking wine served by attentive young catering staff.

I’m at a private view of an art exhibition entitled ‘Inside’ at London’s Royal Festival Hall. Every year, a charity called the Koestler Trust organises an exhibition of artwork by prisoners and detainees. The charitable trust states its aim is to enable inmates to participate in the arts, but in a strange irony – apparently lost on everybody at the event – the private viewing is organised by G4S, the very company which profits from locking many of the artists away, operating some of the UK’s worst prisons and immigration removal centres.

For the last three years without fail, G4S has organised an event at the annual exhibition for its senior executives, prison and detention centre managers, journalists and senior figures in the arts and criminal justice sectors. This year, a name badge was printed for Phillip Lee MP – the junior minister for victims, youth and family justice – although he appeared to be a no-show.

When I arrived at this year’s event, the crowd of 50 or so was overwhelmingly made up of white men in suits, most of whom had gathered at the entrance to the exhibition and showed more interest in the free alcohol, canapés and networking opportunities than in the two rooms of art and spoken word poetry.

About an hour into the evening, the crowd were treated to a speech from Neden, who acted sincere and concerned when acknowledging the challenges of the current prison system.

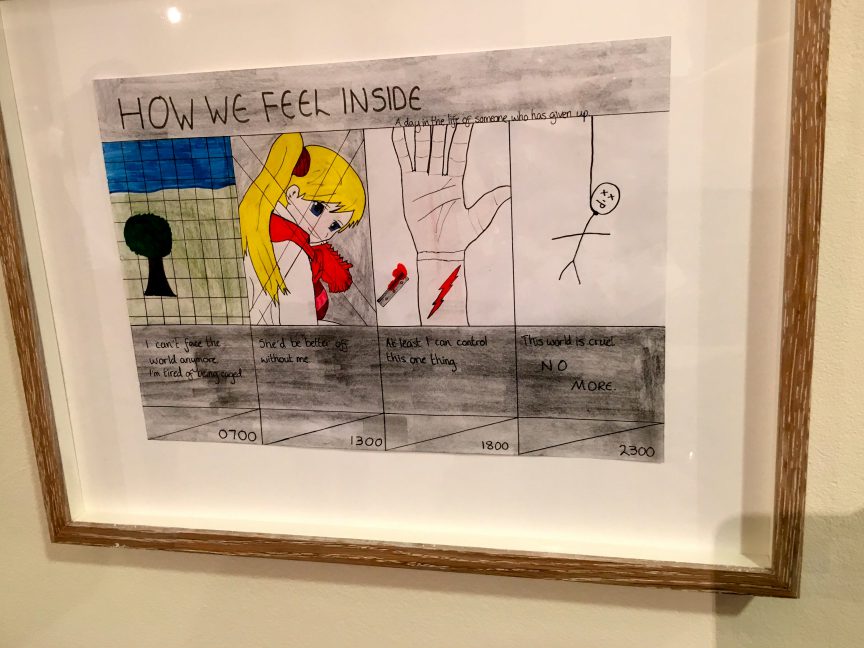

“Levels of violence on the increase, availability and usage of drugs, very sadly self-harm and suicide are at all-time highs. It is a hugely challenging environment,” he said.

He went on to warn that, “having skim-read the first page or two,” a new report on living conditions out the next day by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) would be “sobering reading.”

He was right. The first page of the HMIP report warns: “I would urge readers not to assume this paper is simply another account of some dilapidated prisons, but to look at the details of what we describe, and then ask themselves whether it is acceptable for prisoners to be held in these conditions in the United Kingdom in 2017.”

If Neden had read beyond the “first page or two,” he would have seen that the report is, in particular, very critical of G4S-run HMP Birmingham, which experienced rioting in September.

Prisoners on its B Wing share cells which are just 3.3 metres by 2.2 metres, giving each one only 3.63 sq metres of space. This breaches the European Committee on the Prevention of Torture’s minimum standard of 4 sq metres, about the size of a double bed.

With these criticisms of G4S prisons and detention centres, you might expect the Koestler Trust, a charity concerned with prisoner and detainee welfare, to be hesitant about partnering with the company.

However, chief executive Sally Taylor showed no such qualms. Speaking after Neden, she shook his hand and thanked G4S for its support and the enthusiasm for the Koestler exhibition.

She closed her speech by quoting David Lidington, the justice secretary, who visited a prison in G4S-run HMP & YOI Parc in south Wales.

Telling the story of just one man in a prison that has high levels of violence and self harm, Lidington said it was the work of staff to help inmates maintain contact with their families that had finally made a prisoner realise how much damage his criminal past and his absence had done to the partner and children he loved. The man became determined that on release he was not going to let them down again.

After quoting this story, Taylor turned to the audience of G4S executives: “That’s what you do,” she said. “Thank you very much for coming.”

The relationship between the Koestler Trust and G4S, as well as other private prison contractors, runs deep. On Koestler’s board of trustees are David Banks, former director of G4S, and Herbert Nahapiet of Sodexo Justice Services, which runs four private prisons in England and co-sponsored this year’s Koestler Awards exhibition.

Sodexo and G4S also fund the Koestler Trust, as does England and Wales’s other private prison contractor, Serco, which manages the infamous Yarl’s Wood immigration detention centre.

Ryvka Barnard, campaigns officer at War on Want, told Novara Media G4S’s involvement with the Koestler Trust must not be allowed to detract from its terrible human rights record.

“No charity partnerships or art exhibitions will change the fact that G4S is deeply complicit in abuse and human rights violations here in the UK, as well as in its extensive operations abroad,” she said. “Despite this, the UK government continues to award contracts to G4S, and lend the company other forms of support and promotion.”

She added: “G4S, along with hundreds of other private military and security companies (PMSCs), operate virtually unregulated in the UK and around the world. Public pressure and concrete action is needed to push the UK government to stop awarding G4S with more government contracts and privatising more public services, and to introduce binding regulations on all PMSCs.”

When asked for comment, Taylor downplayed G4S’s involvement in the Koestler Trust but also continued to praise the company.

“G4S is not a sponsor of the Koestler Trust. G4S is a supporter of the Koestler Trust arts awards scheme and this year used our annual exhibition to host an event,” she said.

“Two G4S managed prisons submitted the most entries for the awards this year, and one, HMP Parc, won the most awards. HMP Parc was also mentioned by the justice secretary recently for exemplary work with prisoners families, and I was pleased to refer to this in my speech.”

She added: “Our board of trustees represents a cross section of experienced people involved in the arts and criminal justice sectors. They include two people who used to work in private prison provision, one of whom is currently on the Youth Justice Board, a prison governor, an ex-offender Erwin James, and an ex-chief inspector of prisons, who together with artists, arts professionals and arts advisers guide the work of the trust.”

When asked how much money G4S, Sodexo and Serco give to the trust, Taylor did not comment.

When asked if G4S was using the arts charity to repair its reputation, a G4S spokesperson replied: “G4S has been involved with the Koestler Trust for many years, and this is the third year we have held a private viewing of the national exhibition of detainee art. We are enormously proud to support their work encouraging prisoners and detainees to change their lives through taking part in the arts.

“In our experience art can play an important role in building self-worth, a vital step to rehabilitation. Our role is to ensure that every prisoner has the opportunity to engage with the right mix of education, training and work, to help them turn their lives around.”

As one of the most vilified and controversial companies in the country, and one which relies on public contracts, it is no surprise that G4S is pumping money into improving its public image. But sponsoring an exhibition of art by detainees and prisoners seems so starkly hypocritical, it is jarring to see them get away with it.

While it is understandable that a charity like the Koestler Trust is tempted to take any funding it can get to make its work possible, it needs to think about the message accepting G4S’s money sends, and the way in which its project is being exploited to make a company with an atrocious human rights record look good.

The enthusiasm and complete lack of squeamishness with which Taylor praised G4S, and the board-level involvement of G4S-linked figures, is difficult to understand. The contradictions should not be so easy to ignore.