In the 2015 leadership contest, Jeremy Corbyn stood on a platform that promised honest politics.

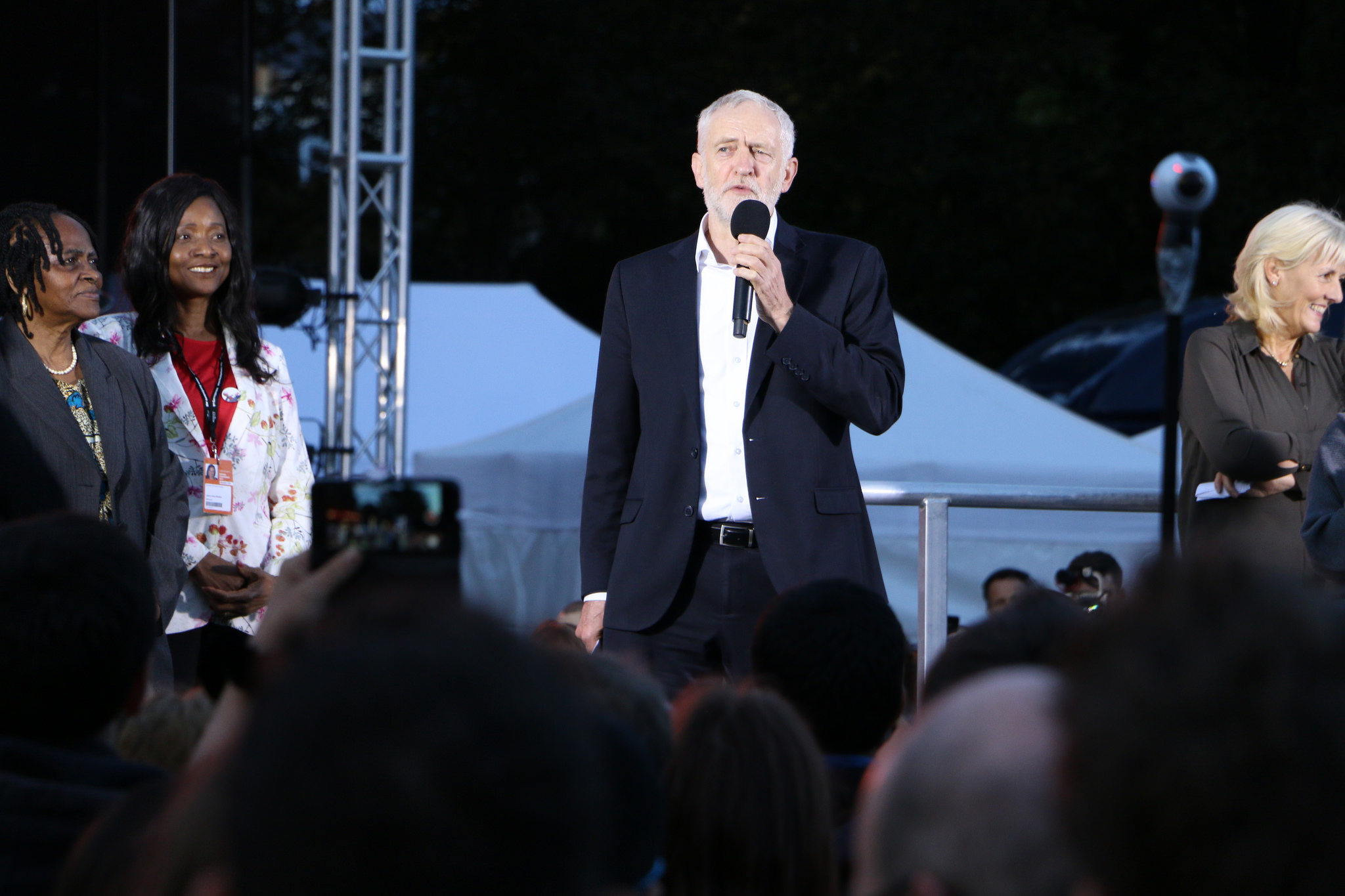

‘What will Labour do about immigration?’ was a regular question in the scores of hustings that were held up and down the country. His three opponents – Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall – answered with the kind of veiled anti-migrant sentiments that had become fashionable in the Ed Miliband era. Corbyn, in contrast, was unashamedly pro-migration. Rejecting the idea that the UK needed stronger immigration controls, he said Labour should campaign on the basis of solidarity and emphasised the need for entire communities to work together. On becoming leader, his first act was to speak at a pro-refugee demonstration in London, a largely symbolic move, but one that appeared to signal he would not personally or politically kowtow to the anti-refugee sentiment that the right had stirred up, aided by left-liberal opinion.

But Labour under Corbyn hasn’t yet fully delivered on the bold declarations made about migration in those heady days of summer 2015. In the 2017 snap general election, the party offered a mixed message. Corbyn maintained staunch opposition to scapegoating migrants, and an early leaked version of the party’s manifesto recognised the “historic contribution of immigrants and the children of immigrants to our society and economy.” Corbyn and shadow cabinet members were also steadfast in their refusal to set a target for reducing migration. Yet the party’s welcome rhetorical shift was not universal and did not directly translate into policy. The final, published version of the party’s election manifesto said, for instance, Labour would “replace income thresholds with a prohibition on recourse to public funds”, which hardly sent out a positive message on migration. This would deny people access to state support if needed and it reinforces a notion that migrants don’t truly belong in the UK.

Labour needs to be bold on migration, and how they do so is a critical question. Many in the party, and the UK more broadly, are susceptible to pandering to anti-migrant sentiments and reinforcing racialised notions of the nation. In fact, the left is by no means immune from taking these dangerous paths. Sections of the party believe entrenched prejudices are too difficult to challenge, and shy away from conversations about race and migration. Meanwhile, others argue Labour must listen to and tacitly agree with fears over immigration – always understood through the disingenuous prism of ‘legitimate concerns’ – instead of using evidence to argue that migration has, in fact, not made the country worse. Making oneself heard in this din is itself a challenge. Pondering what to say and do is another question altogether, a dual problem that embodies at least some of Corbyn’s woes. On race and immigration Labour’s left tend to tick many of the correct boxes, but this needs to translate into a popular, powerful and transformative movement that is rooted in specific anti-racist policies and pro-migration messages.

There is a form of anti-elite politics that has the potential to advocate for a broad understanding of ‘the people’, explicitly including people of colour, migrants and white people, in contrast to the narrower, racialised version appealed to by the ‘populist’ far-right. This is what Corbyn’s Labour needs to build upon. There’s no reason for a popular left-wing project to be anti-immigrant or buy into white nationalist framing – particularly when elites, not migrants, traded away peoples’ rights (in this case anyone outside the wealthy) to give power to big businesses. While Labour is now adamantly anti-austerity, they have not yet attempted to fully shift the framing of migration in an equally dramatic way.

There are people on the left urging Labour to abandon ‘identity politics’ and focus more attention on economic failure. However, it is reductionist to boil anti-migration sentiment entirely down to economic anxiety. Both can and must be done: the party’s past unwillingness to challenge the economic order had nothing to do with privileging the discourse of equality instead. Creating a fairer economic system will not automatically solve racism and xenophobia; prejudice cannot always be understood as a by-product of economics. There are broader issues of national belonging and identity at play, which are rooted in racism and ideas of an idealised whiteness. It is no coincidence that in the weeks after the EU referendum, people of colour – regardless of where they were born – were told they were unwelcome in the UK. The racial element of the Brexit vote has been overlooked and speaks to a much deeper problem of a racialised interpretation of ‘the UK’.

2017 proved the power of Labour’s grassroots movement, which has ballooned in size thanks to the party’s shift to the left. Hundreds of thousands of activists targeted seats up and down the country, helping to deliver Labour one of the most impressive election results in UK history. It is possible and necessary for Labour as a bottom-up campaigning movement to make combatting anti-migrant politics a central part of their alternative vision of the country. The party needs to be part of a project that reimagines the ‘us’ that both defines the nation and stretches beyond national boundaries to form a global movement. In this respect, as a first step, Labour must define the country as heterogeneous and unite the people against the elite. This would require grassroots, democratic engagement at a community level; shining a light on the countless workplaces where migrants and British-born people live and work side-by-side and unite to demand better pay, rights and living conditions. The politics of individualisation has become commonplace in British discourse, but it is not a product of human nature. To revitalise the ethos of collectivism, Labour has been right to argue migration does not make the country worse off. They should continue to explain that the reason behind growing inequality is the broken economic and political system, which favours big business over people, and an unorganised, largely unionised labour force separated along artificial national lines. The politics of divide-and-rule must be revealed and rejected. Here, Paul Gilroy’s notion of conviviality might be helpful:

the processes of cohabitation and interaction that have made multi-culture an ordinary feature of social life in Britain’s urban areas and in postcolonial cities elsewhere … The radical openness that brings conviviality alive makes a nonsense of closed, fixed, and reified identity and turns attention toward the always unpredictable mechanisms of identification.

Labour should champion this form of interaction and openness through grassroots initiatives that challenge misconceptions about migration and the very idea of fixed identities and culture. Building anti-racism into the centre of local Labour activism – as some are seeking to do – can increase interactions between different peoples through popular campaigns and collective struggles, all while questioning the misinformation and prejudice upon which anti-migrant politics is built.

There is a rich history of anti-racist, pro-migrant activism from which Labour can learn in order to help transform the debate about migration and belonging in this country. Some believe that racialised hurdles are insurmountable, but they can be challenged with a politics that highlights humanity, actively combats prejudice, shows that the country’s national story is one of migration and brings people together through collective struggle across the country. Real change is about more than ticking boxes: anti-racist politics must be at the heart of any challenge to neoliberalism if it is to be effective. To borrow from Stuart Hall, “If we are correct about the depth of the rightward turn, then our interventions need to be pertinent, decisive and effective.” Such is the case for an anti-racist, pro-migrant Labour party.

This article is an edited extract of Maya Goodfellow’s chapter ‘No more Racing to the Bottom’ in The Corbyn Effect, edited by Mark Perryman (Lawrence & Wishart 2017). Available here for £15. Enter NOVARA at the checkout for 20% off.

Maya Goodfellow is a freelance writer focusing mostly on UK politics, race, migration and gender, and a member of West Ham constituency Labour party.