The Sofia Solidarity Centre Squat Exposed a Housing Crisis Past Breaking Point

by Matt Broomfield

26 March 2018

Squats are intense by nature. Leave the door open and not only cold winds but cops will sweep through: security and sanctuary are contingent not on the coin toss of making rent, but on the all-but-certain edict of a county court judge.

Opened on Great Portland Street as London temperatures dropped to minus ten during the bitterest of the Beast From The East, the Sofia Solidarity Centre was no exception. It was housing a hundred rough sleepers within a week and close to two hundred by the time its residents were driven out a fortnight later by court order and the threat of bailiffs, the thermometer still hovering below zero.

More precisely, during my two weeks living and working in Sofia, I saw how squats serve to intensify pre-existing conditions. Compressed into the briefest of periods and closest of spaces, tempers sometimes flared and relationships boiled over. But more personal, social and political change was achieved in the pressure-cooker of Sofia than across many months of more pedestrian direct action campaigns.

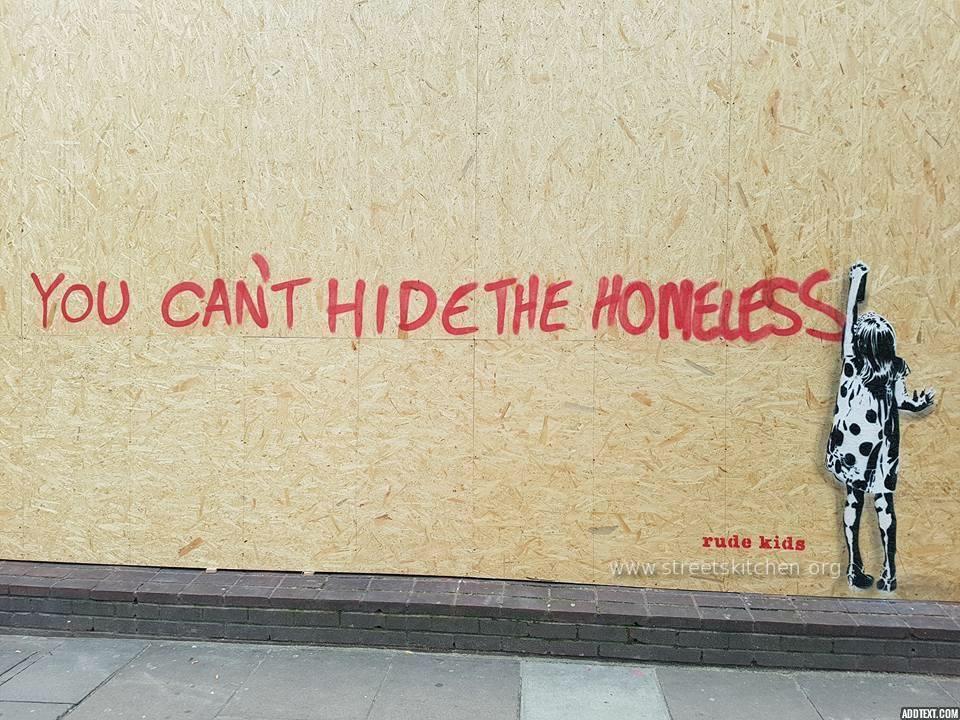

Most of all, the Centre served as a vigorous embodiment of the very worst of the housing crisis, an ineluctable challenge to the government, Sadiq Khan’s council, and left activists alike.

The lethal cold spell which killed a rough sleeper directly outside the Houses of Parliament came on the heels of a furore around plans to fine, bully and socially cleanse rough sleepers out of Windsor ahead of the Royal Wedding. Both have fed into a general rumbling-round of public consciousness toward the skyrocketing numbers of homeless people living on Britain’s streets, which came to one crux in Sofia. (No UK squat has attracted such widespread and uniformly positive media attention in recent years).

Across the last seven years, the amount of government-funded social housing being built has dropped by 97%. Benefits have been slashed across the board, and private-sector evictions have skyrocketed. Nationwide, rough sleeping has tripled in the same period.

Comrades who cracked the building deliberately chose a property held empty as an investment by mega-rich, tax-dodging property developers. We offered shelter there to serial convicts, crack addicts and beggars not only to keep them alive through the cold, but because of the ugly question they insistently asked of a country where “there are ten empty commercial buildings for every person registered as sleeping on the streets,” as one homeless activist at Sofia growled into an ITV camera.

Only about 10,000 of the 300,000 homeless people in London are actually sleeping rough – those who’ve lived sofa-to-sofa or in B&Bs know how close the street can seem. The miseries suffered by Sofia’s residents during their days, years, decades on the street are a distillation of miseries suffered by countless Londoners every day.

At their best, squats unite practical aid with a vocal, visual statement of dissent. They transcend an anarchistic politics of retreat to become a potent political weapon. In the 1980s, America’s National Union of the Homeless (NUH) used co-ordinated squatting of federal buildings across multiple cities to win housing provision for hundreds of members, 24-hour intake in city shelters, the right to vote and public showers – this last by holding “bathe-ins” in public fountains.

Crucially, the NUH’s discourse deliberately targeted precarious workers with slogans like “you are only one paycheck away from homelessness”. Albeit that they are vilified and misbelieved and trudged past moodily on the morning commute, rough sleepers remind housed workers of this fact every day.

By showing how easy it was to house and shelter hundreds of the bottom 1% in society, Sofia likewise made much of the remaining 98% glance sharply upwards at the politicians who have vowed over and again to end rough sleeping.

Homelessness is an oddly bipartisan political issue, often uniting anarchists with soup-kitchen liberals and nationalist small-c conservatives who want to see right done by the veterans on the streets. In Sofia, Irish republicans with militant leanings worked and slept alongside ex-squaddies with six tours of Northern Ireland under their belt. One resident beggar said three separate strangers stopped him on Oxford Street and pointed him in the direction of the squat.

Sofia was an open goal for any member of the Corbyn movement, making a crystal-clear and emotive statement on a critical electoral issue which is often hard for voters to visualise or make sense of. No Labour official or significant figure in the Corbyn movement came along to listen or to magnify the voices of the residents – their loss.

At the same time, though, rough sleepers continue to be spat upon, beaten and murdered in their tents. Addicts and Eastern Europeans grafting on the street, who between them made up 90% of the centre’s population, cannot expect general platitudes about homelessness to crystallise into any actual support.

As we broke the news of the eviction notice affixed to our door, the saddest thing was how calm everyone remained, asking only – and for the thousandth time in their lives – how long? Squatters, rough sleepers, and all of us who struggle under hegemony are so often reduced to begging capitalists for an extra couple of nights here, a little time and compassion there, pleading for scraps and receiving fuck-all in return. We knew we would be out within the week.

We talked about marching on the Royal Courts of Justice on the day of the repossession hearing – but why should we? The real protest was the squat itself, embodying resistance in its day-to-to-day operation.

Placing scores of intensely vulnerable people in close proximity is not something to be done lightly, particularly under intense media scrutiny, but the potency of a squat like Sofia is that it is more than a mere symbolic entity. We did not need to endanger our vulnerable guests, or those with questionable legal status, in a muscular resistance to the coming eviction.

Nor – as is always the fear with squats – did we have to turn them back out onto the freezing streets, snatching away what was offered to leave people more bruised and exposed than before. We could quietly help the overwhelming majority move on to a new place of shelter, knowing that the political point had already been made.

It was being made every day, in the lives saved by off-duty paramedics who arrived guerrilla-fashion with borrowed equipment, in the trained chefs and builders handed tools and helped back into work, in the grown man weeping over a styrofoam tray of lasagne following six weeks spent sleeping in a bin chute. Real direct action acts first and speaks later, and speaks all the louder for it.

As ever, it is the external conditions of impoverishment and political indifference which come easily as I try and describe the vitality of Sofia, while the brief hope and compassion which endured within elude reconstitution on the page. Yet to omit these frailer subjects would be irresponsible, a dereliction of the revolutionary’s most difficult duty — to joy in dark times.

Fortunately, the messages in the visitor’s book we kept by the rattling squat door are earnest and clear, taking flight at the point where I find my voice falters. “For 3 weeks it’s been a home to rest our heads and gather our thoughts, to feel warm food in our bellys and to laugh with new friends…”, writes one.

Another: “I’m here only from one day and I’m starting back to live again. I’v been alrady in many problem but I understand that if I want help my self I have to help all the people that I can.”

They understand the squat was not only a break in a punishing political consensus, but also a window forward into something more.