How Power Hungry Politicians and the Far-right Are Turning Italy Against Refugees

by Hsiao-Hung Pai

22 April 2018

On the day Italy’s general election count ended, Idy Diene, a 53-year-old from Senegal, was shot dead by a local man in Florence. Diene was making a quiet living as a street vendor, keeping his head down, selling tissues and lighters to passers-by. He was about to go to Florence’s central mosque for noon prayers when he was gunned down in broad daylight. The police quickly announced, before any investigation, that it wasn’t a racially-motivated murder. Diene’s family, as well as the city’s African communities, wouldn’t buy it. Diene’s cousin, who also worked as a street vendor in Florence, was murdered in 2011 by a fascist. Diene was not a random target.

Italy’s general election campaign was marked by racial violence and rising hate crime against migrants and minorities. A month prior to Diene’s death, on 3 February, six African migrants were injured in a shooting rampage by Luca Traini, a former candidate for the far-right La Lega (The League, which used to be called Lega Nord, Northern League) in Macerata, a small town in central Italy. Following the fascist terrorist attack (that is what it was), Traini stopped at the town’s war memorial, gave a fascist salute and shouted “Viva I’Italia”.

As counting drew to a close on 5 March, Five Star Movement (M5S) was the largest single party nationally with 231 seats (32.22% of the vote) and La Lega (The League) 123 seats (17.69%). Five Star gained a large amount of support from working-class voters by focusing on issues like a minimum monthly income and labour laws, while including pledges on migration that brought it closer to La Lega. Five Star leader Luigi di Maio said he wants an end to the “sea taxi service” that rescues migrants, in rhetoric not dissimilar to Matteo Salvini, leader of La Lega. (Five Star’s founder Beppe Grillo had said in 2016 that “all undocumented migrants should be expelled from Italy” and in 2017 questioned the role of NGOs in rescuing migrants at sea.) Five Star saw a surge of support in the south. In Sicily, it gained all 28 seats (19 Lower House seats and 9 in the Senate).

Sicily’s shift to the right first became evident in the local elections last November. Matteo Renzi’s Democratic Party was kicked out of power, dropping to third place behind Five Star, who became Sicily’s largest single party with nearly 35% of the vote. The centre-right candidate Nello Musumeci, who won with 39% of the vote, was elected to become Sicily’s new governor. Musumeci had the backing of three of Italy’s most prominent parties on the right: Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (Go Italy), FDL (Brothers of Italy), and La Lega. The government of the island was then handed to a centre-right bloc. Back in November, Five Star was looking to run a region of Italy for the first time – this is now a reality.

La Lega has come out of the election beginning to draw support from Sicilians, too, as part of an alliance with Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and far-right anti-immigrant party FDL (Brothers of Italy). Berlusconi himself, who has had a life-time career in racism and bigotry (he was notorious for calling Islam “an inferior religion” and using his weekly show “The Fifth Column” to report on crimes committed by immigrants, so to incite hatred against them), is well-respected by many here in Sicily.

In the month prior to the general election, my conversations with local residents in Palermo gave me the impression that support for the ideas represented by Berlusconi’s right-wing bloc is widespread. In the run-down estates behind the central station, many residents identified with Berlusconi, despite his notorious association with the Sicilian mafia. A pizzeria worker told me confidently that he will definitely give his vote to Berlusconi’s coalition. Why? “Because Berlusconi is the only one who thinks for the south,” he said with conviction. Then came the predictable: “There are too many clandestine here, too many black people.” Sadly, the economic stagnation meant that this worker’s views are not uncommon, particularly in the impoverished parts of town.

In Via Vucciria, an ancient market founded by North African arrivals over a thousand years ago, I came across residents who see migration from Africa as a negative thing. This is where the artist Renato Guttuso painted the iconic ‘Vucciria’ that in many ways represents Sicilian life. The street seller of a mass-produced ‘Vucciria’ copy told me that he will vote for Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. He proudly pointed to the Milan football logo on his jumper. (Berlusconi owned A.C. Milan football club until last year.) While giving Salvini a thumbs-down, the man said he didn’t like migrants from Africa. Clearly, he sees Berlusconi as representing a “less-extreme” stance on migration policies than Salvini. He then started asking his friend who worked as a waitress in the restaurant next to his store, who she was voting for in the election. “Berlusconi,” she said without a doubt. “You see, everyone in our area supports him,” the man cheerfully said.

For years, the liberal left has thought of Italy as a humane country where refugees are welcomed. You read about the numerous rescues of migrants by Guardia Costiera in the Mediterranean; you hear about the Pope bringing Syrians to the Vatican and continuously rallying for support for refugees. You watch documentaries about villagers welcoming newcomers into their community. Yet, as if suddenly this year, far-right violence increased and African migrants started being attacked and murdered in the streets. Mass deportation of migrants was being shouted about in political rallies. You start to wonder: Has this really happened overnight?

The truth is that the racial violence in Macerata and Idy Diene’s murder in Florence were waiting to happen. They were inspired not only by the far-right – as if that exists in isolation– but by a broader toxic politics of race in Italy that has been worsening since the economic crash of 2008. The fascist Traini’s views are as mainstream as those advocating deportation on TV screens. Like the political breeding ground that eventually led to the murder of British MP Jo Cox, the anti-migrant, anti-refugee poison at the top of Italy’s political agenda was the context in which violence and murder were allowed to happen.

Faced with an economy that has stagnated for years, with one of the highest debts in the EU and 11.4% unemployment nationally, all political parties here have been able to capture the public mood and successfully put the blame on “outsiders” – despite the fact that migrant labour has filled the labour shortage created by the mass youth emigration (due to high youth unemployment of up to 36% nationally) and has been sustaining many of the country’s industries. The majority of Italy’s current 620,000 migrants are, in fact, not in the state-funded asylum reception system but working in agriculture and other labour-intensive sectors that have been largely abandoned by local labour. Nineteenth-century working conditions have been imposed on these migrant workers, who have neither rights nor protection, with industries breaking the law in their extreme exploitation.

While Italy survives on the sweat and blood of migrant workers, Matteo Salvini, the head of La Lega, to which Traini belonged, has incited hatred towards migrants for years. Yet, in the months preceding March, we had the spectacle of the plastic face of Berlusconi, like a joke mask of himself, laughing at people for thinking he’s the face of reason as he brought the far-right on to the centre of Italy’s political stage.

During these months, with help from the mainstream media, Italy’s election campaign went on targeting migration as the main ill, focusing the entire country’s attention on the transient minority whose labour has in reality kept the country going. La Lega promised to introduce mass deportations of asylum seekers to Africa as part of a radical reshaping of migration policies if it won the election. Even in the aftermath of the Macerata terrorist attack, Berlusconi blamed migrants, saying that they were “a social time bomb ready to explode” and promising that if elected, he would deport 600,000 migrants. The neo-fascist party Forza Nuova (New Power) – one of the far-right organisations whose members were involved in the Bologna bombing that killed 85 people in 1980 – ran a demonstration in Macerata, where its leader Roberto Fiore called the fascist shooter a “victim”.

The Italian media has played a crucial part in mainstreaming and normalising politics of race by propagating and pandering to racism, not least during the election campaign. Following the Macerata attack, the media analysed the psychology behind the shooting (calling it “the act of a lunatic”) instead of defining it as a far-right terrorist attack. We see the same response following Idy Diene’s murder, where the gunman was described as someone with mental health issues who was attempting suicide before killing Diene.

The media and social response mentioned above was strikingly similar in the aftermath of the shooting a few months earlier of a 19-year-old Gambian teenager Alagiee Bobb by the manager of his asylum shelter in Gricignano d’Aversa in Casertano, north of Naples. Apart from the response from migrants who organised demonstrations showing solidarity with Alagiee Bobb, there was little media or social attention: How could something like this happen in a shelter that is supposed to offer protection? No questions were asked by journalists and society.

Sicily is an amalgam of civilisations due to its history of many conquerors and influences; it’s a culturally diverse place well praised for its tradition of receiving newcomers. However, in recent years, the economic bad times and media manipulation and misrepresentation of the “refugee crisis” have changed perceptions of some residents here. The island has been sucked into Europe’s machine of border defence and asylum management, being made the frontline of a frontier state. The right has been able to capitalise on the frustrations of Sicilians with their economy and channel their anger against the establishment on to “outsiders”. Alberto Biondo, a Palermo-based migrant rights activist, said:

“Growing racism is a phenomenon that’s happening all over Europe. Sicily’s no exception. We’re going back in time… Racism is promoted by Europe’s politics; the decision to close all the frontiers and to invest in security has enhanced nationalism that previously perhaps seemed hidden since World War Two but is now returning with greater force.”

Racism has become part of life for those who arrive here for protection following the dangerous sea-crossing. The occasional racism that migrants experience from local residents in the towns where they happen to be is traumatising, especially because migrants who end up here have come via Libya, where the majority of them have been through some form of slave labour, physical torture or abuse. Children, naturally, find it much more difficult to cope. I have talked to several under-18s from Gambia about their experience with local racism and their first response to it was confusion, followed by a great deal of anxiety and anger. One of them, Modou, has been transferred from shelter to shelter on this island in the two years I’ve known him. The first time he ever encountered racism from local residents was near his shelter in Licata on the southern coast. When he and other Gambian boys went out to the beach, local young men would shout abuse at them, which stopped him from going there again, for fear of potential violence. Modou was also upset by the racist graffiti on the wall outside the shelter. “I don’t understand why they hate me,” he said to me often. These are children who had not even been given counselling for their ordeal at sea. To be faced with racism is often the turning point of their relationship with the local society in Europe.

Here in Sicily, the racism exemplified in the institutional and social response to the Macerata shooting and Idy Diene’s murder is, sadly, familiar to migrants. People in Modou’s situation cannot simply walk away from incidents of racism – because life inside shelters and camps demonstrates to them, day in day out, where they are in the European racial hierarchy. It impacts on him as deeply as the threat of racial violence outside the door. For Modou and everyone else who has been trapped in these shelters, racism is ingrained in the system that grades them as sub-human and second-class.

Modou empathises with the plight of other Africans in Europe. He cried when Alagiee Bobb, who he’d never met, was shot. Bobb’s camp hosted 159 asylum seekers back in November and was known to be poorly equipped. There was not even heating in the winter. Bobb was among those protesting against the living conditions for several days before the shooting, which happened during a confrontation that escalated. “He was shot in the mouth twice,” Modou said, desperately upset. What happened to Bobb is symbolic of the systematic degradation and subjugation that characterise daily life inside these asylum shelters and camps. The brutality lies in the fact that Africans are seen as inferior and the “bottom race”, who deserve inferior treatment. For instance, the demand for heating, regular water supply and adequate food provisions are often treated by staff and managers in these reception places as unreasonable and “asking too much”.

Activist Richard Brodie of Porco Rosso, a cultural association located in the middle of Ballaro, Palermo, said that racism is widespread in the shelters and camps as well as in society.

“There’s the basic level of ignorance and people experience it in the system, which is based on isolation and separation of migrants… You’re registered to see different doctors if you’re a migrant. The staff in shelters and camps often say to migrants from Africa who demanded heating: ‘You don’t have heating in Africa, do you?’ People are given white pasta (without sauce or anything on it) every day and are told that they don’t fit in and don’t like Italian food when they complain about it… The journalists say migrants come here and complain about not having wifi in the shelters – But how are they going to talk with their family otherwise?”

Porco Rosso, the association which he and colleagues set up, also works as a migrant drop-in centre, offering assistance and advice to people who can’t have their basic needs met in their shelters. Across Sicily, voluntary groups like this are providing services to migrants while their shelters are failing them. That included taking pregnant women to the hospital when no one else was there to help, as Brodie revealed.

Although those living in the reception system are only a tiny minority that takes up less than 5% of the entire migrant population in Italy, they’re scapegoated for the chronic problems of poverty and unemployment. The reality is that the asylum reception system has created many jobs for local people and local entrepreneurs have benefited from setting up shelters and accruing state funds. The mushrooming of privately-run shelters has led to misery for asylum seekers who are treated as commodities (as each person brings in state funding to the shelters) in the local asylum enterprise. The setting up of hotspots in Sicilian towns, as part of the EU project for filtering displaced people from Africa and Asia, practically created open “migrant prisons” as many activists call them. Migrants who go through the asylum system simply become victimised by it, their life put on hold and their future in the hands of profiteering managers and owners of reception businesses. However, the reality is kept away from the public gaze. Instead, they are told lies – for instance, by La Lega, that “migrants receive 35 euros per day from the state”. These lies are then recycled and circulated by the media. (The fact is that the state allocates 35 euros per adult to the shelters/camps who decide how they use the cash.)

As a result, the anti-migrant message of Berlusconi’s centre-right coalition has gone down well generally in the Mezzogiorno region of the south. Meanwhile, in Sicily and the south, La Lega is still seen by many as a northern thing, given Salvini’s years of telling southerners how lazy they are. Five Star, instead, was able to win hearts for its clear anti-establishment, anti-mafia, anti-EU message. Rabih Ja’afar, a political science student at the University of Palermo, said that Five Star has attracted many young voters as youth unemployment reaches well above 50% in Sicily and their future prospects aren’t bright here. For the young, the alternative to a life of low-paid, dead-end jobs is to migrate out of the island – a familiar pattern in southern Italy generally as many young people feel they don’t have a future in their hometowns. Scepticism towards the EU was rising as result of years of EU-imposed austerity, felt most strongly in the south; Five Star and La Lega were the clear beneficiaries, who have both talked about withdrawing the country from the euro while proposing drastic changes in migration policy. Renzi’s Democratic Party, meanwhile, lost out here, since it moved away from the centre-left. It is seen as a party that implements austerity and “not for the people”. Rather, Renzi himself is nicknamed “Mr Bean”, self-centred and deluded. “People tell him to go back to England where he comes from!” said Ja’afar.

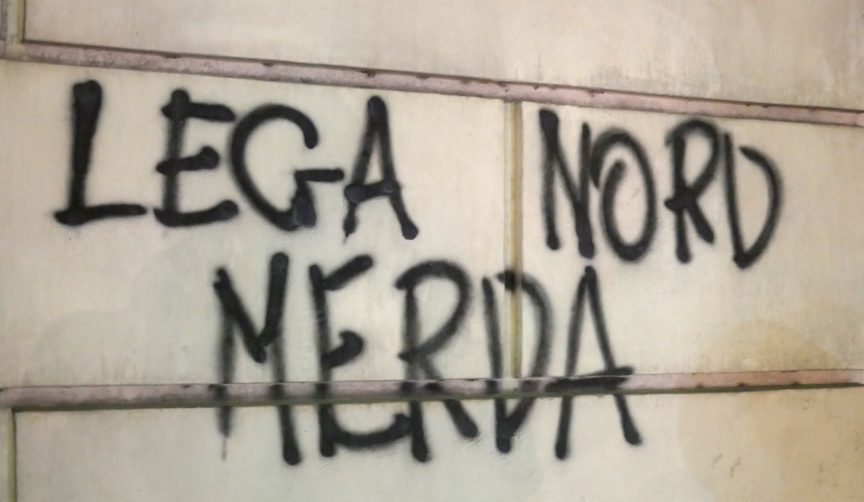

Meanwhile, despite the decline of the centre-left, not everyone is buying the politics of the Right. You can find anti-racist street literature all over town. For instance, in Via Lincoln, known by some as Palermo’s “Chinese area”, you couldn’t help noticing the graffiti on the walls along this street – “Lega Nord merda,” (Northern League shit), “Salvini topo di fogna” (Salvini sewer rat). Disillusionment with the entire establishment is prevalent, which led to people’s choice to abstain in the election. In a busy café on Via Oreto, a diner in his forties debated passionately with the waitress about the elections. He told me that he was voting no one, as “they’re all rubbish”. “Italy’s finished,” he said angrily. The waitress shook her head, expressing her disapproval for Berlusconi and his cronies. When asked who her electoral choice might be, she sighed and continued shaking her head. Sicily has the country’s lowest turnout, 62%.

Today, anti-migrant sentiment is no longer a stranger here – quite different to the image you would see on the travel brochures for this part of Italy. The clear signs are on the walls in the streets of Palermo, where posters of anti-fascist marches are everywhere to be seen, indicating the growing threat of racist and fascist political forces. Anti-racist activists, mainly from small, left-wing groupings, are quick to organise. Some antifa are prepared to use physical force to fight the fascists. Forza Nuova (New Power) teamed up with Tricolour Flame to form the “Italy for the Italians” coalition, for the general election. As its leader/secretary Roberto Fiore, who claimed himself to be a fascist, was scheduled to come to Palermo for an election rally, Massimo Ursino, one of group’s founders, was bound with tape and beaten by a group of anti-fascists near their headquarters, four days before Fiore’s arrival on the 24 February. “We tied him up and beat him to show that Palermo is anti-fascist and there’s no place for men like him here,” activists said. While the press, again predictably, condemned the action as “a gesture of extreme madness”, what was not discussed by journalists was the fact that Ursino is a dangerous and violent fascist who was sentenced to prison in July 2006 for kidnapping and beating two Bangladeshi migrants in Palermo. He is locally known for hate crime against ethnic minorities.

Activist Alberto Biondo said:

“Fascism is not accepted in Italy’s constitution but fascist political parties have not been stopped because there is no interest in stopping them… There was an interest in maintaining the regime of terror… The likes of Salvini, Casa Pound and Forza Nuova could actually not exist according to the constitution. But they do and are supported. Just look at what happened now: Those responsible for the attack on Massimo Ursino were immediately arrested, but what the fascist and his associates did and are doing, i.e. conducting violence against migrants, was never punished – and if ever they were punished, it usually took a much longer time.”

Biondo thinks that mainstream racism is the context in which the seeds of fascism are planted. “Although the number of people who’re drawn to the politics of the likes of Forza Nuova is currently still small and the average Italian voter may not accept the fascist violence, they agree in general with the idea of ‘Italian first’ and go along with the acceptable form of racism.”

State institutions are certainly on the side of fascist organisations. In Palermo, Forza Nuova held a rally earlier this year. “As a fascist party they shouldn’t be allowed to demonstrate,” Biondo said. But they were given permission and protection by the police. “The ones who will be suppressed will be the anti-fascists,” he said. “This is always the case.”

Palermo’s anti-fascists showed their strength by turning out thousands of protestors on the day of the Forza Nuova rally. Among organisers of the demonstration were members of Potere al Popolo (Power to the People), a leftwing coalition of parties and groups that was launched last December and ran for the general election. Alaji, a young man from Gambia, joined the march. He said his friends had been too frightened by the possible presence in town of fascists to join the march. This was a common theme, with few from ethnic minority communities attending, but Alaji decided that he should make a stand and join other anti-racists.

Alaji knows that the future is truly grim for migrants, who are well aware that their presence has been the centre of debate – a debate they have not been allowed to participate in – in the recent election campaign and in public discourse in general. He told me: “My friends and I are saddened by the racism from politicians in the election campaign, but it hasn’t surprised me, because racism is out there in society.”

Numu Touray, a DJ and presenter for Radio Asante in Palermo, whose audience are primarily migrants, told me that people are feeling confused, frustrated and fearful. Not only do they fear that the future change of migration policies will impact on their lives negatively, but also more immediately, the racial violence, especially since the murder of Idy Diene, has made them feel unsafe. “People need to organise themselves and do something about it,” Touray said.

At the same time, there is also the recognition among migrants of what they actually do for Italy and Europe. When asked how he feels about Salvini’s pledge about mass deportation, Alaji paused but responded with confidence: “It’s impossible for them to deport us. What are they going to do without us? They’re making money from the camps; they’re making money from us working in the fields… Italy will collapse without us.”