This week the Guardian began an ‘investigation’ into the rise of what it terms the ‘new populism’. To establish first principles, one of the opening articles in the project attempted to define the often nebulous term.

Interestingly, that primer failed to mention two leading theorists on the subject – Jacques Ranciere and Chantal Mouffe. What’s more, it denigrated the field’s most original thinker, the late Ernesto Laclau, insinuating he was needlessly verbose and not worth reading.

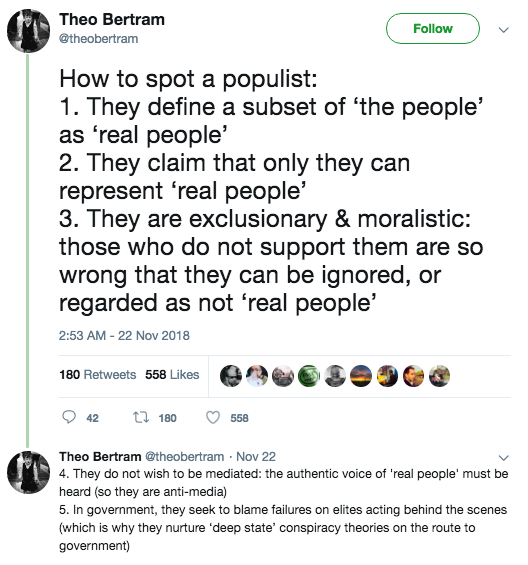

In spite of this, the article was useful in serving to crystallise the common sense of populism from a centrist perspective – and how it ignores its democratic potential. A Twitter thread written a few days later by Theo Bertram was also helpful in that respect, the former Labour staffer proffering tips on how to ‘spot a populist’:

While a provocative summary, Bertram, like some at the Guardian, would benefit from reading Ranciere. What they identify as qualities unique to populism are, in fact, characteristics of politics more generally. Liberals have historically tried to suppress the category of the political, as Carl Schmitt noted, rendering other fields of social life subject to contestation instead – what clothes, food or cleaning products you use – while turning the category of politics into a neutral field of economic management where nothing really changes.

When the centrist intelligentsia dismiss populism, placing the far right and socialist left alongside one another, they do so out of disdain for radical democracy and, in the context of a decade long crisis of capitalism, the category of politics itself. But history has returned, and there’s not much they can do about it.

It is impossible to have politics without ‘the people’. That is because ‘naming the people’, as Laclau calls it, is a core feature of any mass politics seeking to engage the public. Importantly, the people are just as necessary in a technocratic account of the good society, only for them the masses must be defended from themselves through the superior wisdom of expert elites. Thus for liberals, the figure of the people often serves to uphold anti-democratic impulses rather than underpin democratic sympathies.

While limited, and cynical about the scope of authentic democracy, this vision is nevertheless preferable to the politics of the far right. There the focus instead is on the unique merits of a specific ‘folk’, where allegedly biological or cultural traits are elevated in determining who deserves political representation. In 1930s Germany this was nordic ‘aryans’, for today’s ultra-nationalists it is the white ‘natives’ of Europe and the US.

Rather than presuming people must be defended from themselves, or that the shared ‘we’ need be determined by some alleged ethnic heritage, left populists focus on self-government and radical democracy: not just at the ballot box but the workplace too. Here the elite is rightly attacked because the interests of the wealthy cannot be squared with those of the exploited. Highlighting such a cleavage is not demagoguery, as centrists submit, but simply consistent with how capitalism has functioned over the last two centuries.

By extension, any successful electoral politics is based on claiming an ability to represent ‘the people’. For New Labour and the Tories, that meant a ‘we’ forged around economically productive citizens – ‘hard working families’, ‘those who want to get ahead’, ‘strivers not skivers’ – placed in opposition to the ‘workshy’ (read disabled, sick and those living in post-industrial areas) and undocumented immigrants.

So when ‘centrist heavyweight’ Hillary Clinton says Europe must curb immigration to stem right wing populism, she too is naming the people. Troublingly, however, it is the same one as the ultra-nationalists she believes she is counteracting. The idea that, as Clinton states, “Europe has done its part” on helping refugees is absurd. Europe’s powers, specifically Britain, bear significant responsibility for instability in those regions where displacement is happening, while 84% of global refugees live in developing countries rather than wealthy ones.

Clinton’s preference to partly adopt the people as advanced by the nationalist right somewhat explains why she lost to Donald Trump. The alternative ‘people’ Clinton and her wing of the Democrat party could name – working class Americans as championed by Bernie Sanders and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez – is impossible. The reason? It conflicts with the economic interests politicians like her are supposed to advance. You can’t attack a rigged system when you want to maintain it.

Importantly the Guardian ‘investigation’ fails to distinguish between populist rhetoric and policy, discarding analytical nuance in the process. This is important because Barack Obama, the doyen of its leadership, adopted the most populist register of any living US politician in his 2008 election bid. Powered by phrases like ‘yes we can’, the proclaimed protagonist of those efforts was not Obama himself but ‘you’, ‘us’ and ‘we’. The then senator for Illinois even tried to situate his candidacy within the historic sweep of the American story, his biography a single piece within a mosaic tending to an ever ‘more perfect union’. His soaring words, whatever his other flaws, were anything but those of a technocrat. And yet, according to the Guardian, Obama was a ‘non-populist’.

A decade earlier Tony Blair was capable of similar feats, his 1999 speech to Labour conference an outstanding example of populist rhetoric. There he said things his inheritors now decry as obnoxious, labelling William Hague’s Tories as ‘weird, weird, weird’, proclaiming the “the elite have held us back” and attacking “establishments that have run our professions and our country (for) too long”. It is an excellent speech and undeniably populist in tone, even paraphrasing Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Somewhat conveniently, this also doesn’t merit a mention by the Guardian.

It’s no accident that the two most successful ‘centrist’ politicians in recent years articulated precisely the kind of politics the Guardian now identifies as both new and counterproductive. They are neither.

Which is why the paper’s decision to pursue its ‘new populism’ project is a symptom of centrism’s death. That is not to say the wisdom of moderating different views has disappeared – nor should it – but a politics which seeks to triumph by relating to two opposing and static extremes makes little sense in a post-crisis world. That’s because previously unthinkable solutions, such as social housing or rapid decarbonisation, are now viewed by many as necessary rather than preferable.

One thing is for sure: the centrist intelligentsia – or what remains of it – have completely lost their way. They aren’t coming back any time soon. The only meaningful socialism in a post-crisis world, given the challenges we face, is necessarily left-populist – in both rhetoric and policies.