Despite the last four years being a time of unrivalled volatility in recent British history, some hardy perennials have persisted.

One is that Jeremy Corbyn will ‘destroy’ the Labour party – although it’s not quite clear how given he oversaw a large increase in its share of the vote at the last general election. Another is how Jacob Rees-Mogg retains a measure of affability, at least among Tory voters, despite doing things like defending the use of concentration camps.

But perhaps the most enduring has been the whispers that centrist MPs will break ranks with Labour. Today, finally, it happened.

Placed within historic context, the formation of the ‘Independent Group’ not only makes sense, but is predictable. The last two major crises of capitalism, the Great Depression of the 1930s and stagflation of the 1970s, both precipitated a crisis of the British state and, with it, the Labour party. This found expression in two splits separated by five decades: the first in 1931, the second in 1981.

In May 1929, Ramsay MacDonald led Labour to a historic breakthrough when, for the first time, they became the largest party at Westminster. They lacked a majority, however, and in order to govern depended on the confidence of the Liberals for MacDonald to remain as prime minister.

When the Wall Street Crash unfolded that autumn, the global economy went into meltdown. Within a few years the scope of such calamity was unprecedented, if less keenly felt in Britain than the US. Between 1929 and 1932 unemployment more than doubled in the former, while industrial production fell by a quarter. More troublingly for Britain – at that point still the world’s leading trade power by virtue of its empire – world trade came to a standstill. British trade fell some 60%.

This all took place before Keynes published his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936, written in response to such events. Labour, without a modern account of macro-economics, lacked an intellectual framework to make sense of the crisis and how to resolve it. Despite that, the majority of the party instinctively rejected budget cuts and austerity, the very measures being proposed by the civil service and parties of the opposition. The alternative was a budget deficit and, for the establishment, this was unacceptable.

It was in such circumstances that MacDonald, along with several other Labour MPs, agreed to form a National Government with the Tories and Liberals. As members of the new ‘National Labour Organisation’ they were expelled from Labour, a party to which MacDonald had belonged since its inception. He remained the country’s prime minister for another four years. Whether his primary motivation was personal ambition or servicing the ‘national interest’ is impossible to reckon. Suffice to say, one often acts under the guise of the other.

Precisely a half century after MacDonald was banished from Labour, another split took place – only this time in opposition instead of government. And rather than being expelled, the self-styled ‘Gang of Four’ – comprising Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers and Shirley Williams – chose to leave the party with a plan.

While only Rodgers and Jenkins were members of parliament at the time, they would ultimately manage to take another 26 Labour MPs with them. For all the talk of this new formation reaching out across party divides, only one Tory, Christopher Brocklebank-Fowler, actually took the gamble. He, like most of his newfound colleagues, would lose his seat at the following general election.

In contrast to a half century before, political circumstances seemed highly amenable to what was now called the Social Democratic party (SDP). Unemployment had doubled in the two years since Margaret Thatcher became prime minister, while Labour remained unable to offer a vision beyond the nationalisations characteristic of its success in the immediate post-war period. Furthermore, on issues like nuclear disarmament and membership of the European Economic Community (EEC), the party’s direction was viewed as increasingly at odds with the majority of public opinion. The SDP, now in alliance with the Liberals, had everything to play for.

The hype around the new party was so great that one poll, conducted by The Telegraph in late 1981, had the SDP-Liberal Alliance polling at more than 50%. That same year David Steel, leader of the Liberals, told members at party conference to go “back to your constituencies and prepare for government.”

While that turned out to be absurd hyperbole, in terms of electoral share the SDP-Liberal Alliance made an astonishing breakthrough in 1983 as they amassed 25% of the vote. And yet despite being only 700,000 votes short of Labour, the nature of Britain’s electoral system meant they gained just 23 seats.

Yet the SDP were not inconsequential. Without them it is unlikely Margaret Thatcher would have won in 1983, let alone another election four years later. While commentators are keen to highlight how Labour’s left-wing policies made them ‘unelectable’ that year, it is conveniently forgotten how they led the Tories in every poll, except one, between the 1979 election and the birth of the SDP nearly two years later.

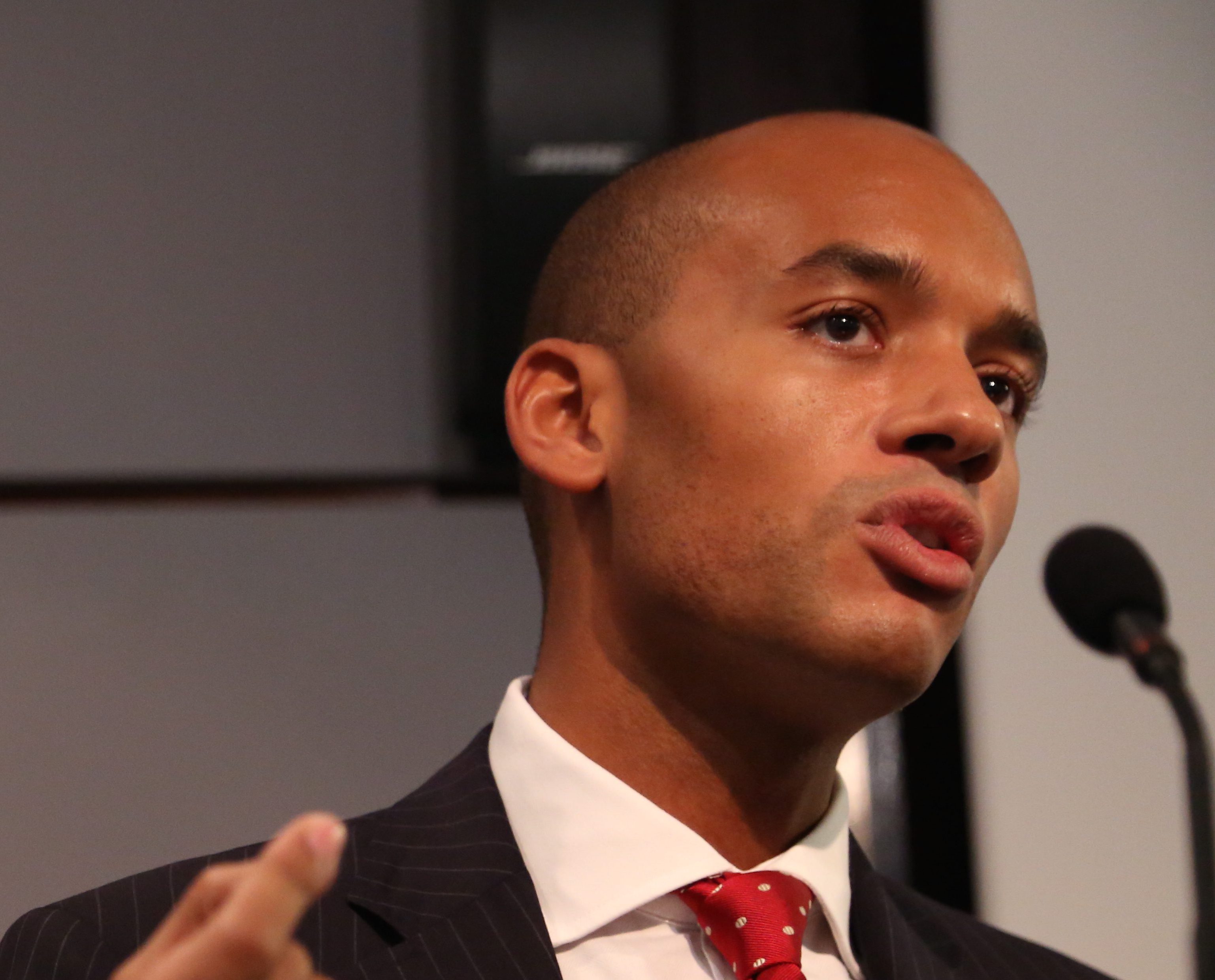

So what of today’s split? In reality it shares few features with previous efforts. Ramsay MacDonald chose to effectively cross the floor while prime minister, David Owen had previously been a foreign secretary and Roy Jenkins president of the European Commission. By comparison, the likes of Chuka Umunna, Chris Leslie and Gavin Shuker have never held a meaningful position in government.

An outgrowth of the personalities is the policies – or rather lack of them. What does this new group stand for? What might we expect in a manifesto?

Angela Smith is unusually outspoken in her defence of water privatisation. Leslie, who has been in parliament for 17 of the last 22 years, doesn’t appear to have much of a legacy beyond saying Labour should resemble Which? magazine. Shuker once threatened to resign over same-sex marriage. Umunna has been both for and against Labour implementing the IHRA definition of antisemitism. The same applies for a second Brexit referendum.

There are hints of a grander strategy. The Progressive Centre UK, a think tank set up last year, has Umunna on its advisory board. Indeed despite his role being unclear, the Streatham MP enjoys a salary of £65k, or £450 an hour.

Even here, however, any sense of a coherent agenda is startlingly absent. Its mission states the Progressive Centre is “an international ideas exchange – connecting progressives from across the UK”. Others on its advisory board include Jane Merrick, June Sarpong and The Economist’s Jeremy Cliffe. In terms of proposals, there is nothing beyond cliche, platitude and repeating the words, “…but Justin Trudeau”.

For all the criticisms of Labour, and there have been many in establishment media, their agenda for government is beyond doubt. They offer a distinct alternative from the status quo – on tuition fees, industrial policy, work and public services. Those comprising the Independent Group, by contrast, share little but a capacity to point at politicians – Matteo Renzi, Pedro Sanchez, Emmanuel Macron – who, within a matter of months, fall to historic levels of disdain in their respective countries. You’d think that might make them think more deeply. Apparently not.

Most importantly, the circumstances in which the Independent Group now finds itself, certainly compared to 1981, are perilous to say the least.

Those areas initially most susceptible to the rise of the SDP – university towns and wealthier metropolitan areas – now tend to be bastions of Corbynism, the social base of which is relatively straight-forward: public sector workers, BAME communities, university graduates who feel they’ve lost out, trade unions, older generations who drifted away from the party under Tony Blair, those deeply politicised by austerity. It is unclear precisely how much of this a new centrist party, committed to the existing orthodoxy, hopes to gain. They might insist in calling themselves mainstream, but the fact not one member of the new group will hold a by-election has a simple explanation: they would all lose very, very badly.

What’s more, beyond Brexit there are no discernible opportunities for them, with momentum pushing in the opposite direction. Unlike the early 1980s, it is the left, not the right, which is framing the emerging political zeitgeist. The same week The Economist had the rise of ‘millennial socialism’ as its cover story, Britain’s Generation Z – the birth cohort which comes directly after – brandished their radical credentials by taking part in a nationwide ‘climate strike’. Chants included ‘Fuck Theresa May’ and ‘Tories, Tories, Tories, out, out, out’. As with their older friends, family and, one day, colleagues, they will earn less than their parents, experience higher levels of indebtedness and enjoy a significantly reduced welfare state. They will also have to address major threats such as demographic ageing and climate change. They are angry for a reason and it is completely justified. A reheated politics from the 1990s doesn’t interest them.

The electorate of the 2020s, both sides of the Atlantic, is coming into view. It doesn’t appear particularly disposed to incremental adjustments to what it views as a broken status quo. 38 year ago when the Gang of Four made its ‘Limehouse Declaration’, the radical left was viewed by most as the politics of the past. Now a majority of Americans under 30 prefer socialism to capitalism, as do most Brits. On a policy basis, Labour’s position on utility nationalisation, wages and taxes can only be described as the centre-ground of public opinion.

The new obsession with ‘populism’ among establishment media is a morbid symptom of how their own politics no longer make sense. In order to justify themselves they have resorted to confecting an imagined unity between the ‘extreme’ right and left so that, by inference, a large centre-ground remains vacated. The only problem is – as polling for the Liberal Democrats repeatedly tells us – this is entirely in their heads. It is this inexistent electorate which the Independent Group hopes to appeal to.

Even with magnetic personalities at the forefront and a well-funded, meticulous operation behind, a new centrist party would struggle to retain a single MP after the next general election. While the splits of 1931 and 1981 destroyed Labour as a party of government for a generation, this time looks different. Importantly, it seems almost every Labour MP recognises as much.

What we are seeing isn’t the launch of a new politics, it’s the old one sailing off in a lifeboat. Floating towards an empty horizon, the Independent Group has no idea where it is going or what forces are pushing it.