‘They should be chased out of town’: How a South Coast Council Is Failing Homeless People

by Natalie Leal

29 April 2019

Right now there are seven people living in the stairwell of a multi-storey car park in Bognor Regis. When you first enter there’s no sign of anyone, but after a couple of flights of stone steps you come to the first sleeping bag, next level up, another sleeping bag, up a few more steps and another pile of belongings, and on and on until you reach the top. From here there are views across the rooftops and chimneys of the small seaside town in West Sussex, to the South Downs beyond.

But while people are sleeping in a stairwell for now, there’s a good chance this hidden makeshift hostel will be dismantled soon. They were all “moved on” from the High Street last week, one homeless man tells me. Everyone sleeping in shop doorways or tents was “served notice”, says Paul — not his real name — and told their stuff would be taken within 24 hours if they didn’t remove it.

Arun District Council, together with Bognor Regis Town Council, the police and a group representing town centre shops and businesses recently got together to produce a ‘multi-agency action plan’ after concerns were raised about the high number of rough sleepers in the town centre. But the concern seemed to centre around the impact on local businesses and the appearance of the High Street as opposed to concern for vulnerable people’s welfare.

The rising tide of need has been met by falling local authority budgets. From September 2019, West Sussex County Council is to begin a series of cuts which will see £4 million slashed from its £6.3 million housing related support budget by April 2020.

During a March local council meeting one frustrated Bognor town councillor, Cllr. Goodheart said:

“The negative effects this [rough sleeping] is having on the Town Centre for the businesses, residents and tourists has become a problem that needs to be resolved.”

He went on to suggest that concerned members of the public should make a citizen’s arrest to stop people begging on the streets.

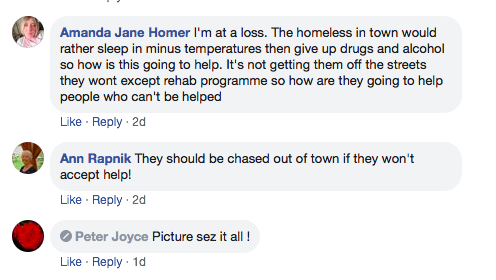

UKIP Arun District Councillor Ann Rapnik recently commented on a post in a Facebook forum that homeless people who didn’t accept help “should be chased out of town.”

Following complaints and concerns, on 19 March Arun District Council applied to West Sussex County Council to be granted new powers to take away rough sleepers’ belongings. Tents, sleeping bags, clothing — anything left unattended — can now be removed from public areas because, in the words of Arun’s leader, Councillor Gillian Brown, rough sleeping has been “a serious issue in Bognor Regis for some time. It does need to be dealt with.”

Arun community manager Georgina Bouette told the Bognor Regis Post:

“We put a notice on their site 24 hours before we intended to act. A lot of the stuff we remove is clearly in a state of disrepair, either sodden or it has been damaged or it constitutes a hazard to other people. That is disposed of”.

Liz Latter, director of an organisation called Radio Respect — a community radio station dedicated to mental health, which works with homeless people in Bognor — doesn’t think this approach is helpful. “All the councillors are seeing is that the mess is ruining out seaside town, they’re not worried about the actual problems that these people have” she says.

Paul has been sleeping rough for a few months, since his landlord evicted him without notice when he was a few days late paying his rent. “I went away for a few days and texted my landlord to tell him I would pay the rent once I was back after the weekend,” he says, “[but] when I came back, all my stuff had been moved out, that was it”. It was an informal arrangement and there was no contract so Paul found himself out on the street.

The stress of being suddenly without a home exacerbated his mental health problems and meant he quickly lost his job as a chef in a pub. “How can you work if you don’t have a home?” he asks.

This is where the safety net of the state should have caught him, but instead life got worse. Paul applied for Universal Credit but says he was turned down because he didn’t have a UK passport. Originally from Germany, Paul moved to the UK 25 years ago, but despite living and working here all that time he has been told he doesn’t qualify for the state benefit because he can’t prove he lives in this country.

“I never got a passport, I didn’t need one,” he explains. He is appealing the decision, he says, but that is likely to take months.

While he waits, with no money or accommodation, he relies on Bognor food bank and Radio Respect, which is based in a record shop opposite.

CEO Chris Collins set up Radio Respect seven years ago while working as a mental health support worker. He wanted to provide support to the community in the evenings so started to broadcast from his garden shed as a way of helping vulnerable people who may be feeling alone.

Recognising the link between homelessness and mental health problems, Collins and director Liz Latter decided to open up the shop to the growing number of homeless people in Bognor, offering hot drinks, clothing and blankets. The main thing they want to provide, says Latter, is a safe space to have a sit down and a cup of tea every day of the week, when other day services in the town are closed.

Latter says the number of homeless people in town is growing. As in Paul’s case, Universal Credit often plays a part in why people have lost their homes. Some are struggling to make a claim, “the amount of paperwork they ask for is ridiculous,” Latter says — “how are you supposed to keep all of that on you when you are living in a sleeping bag?”. The other day a man came into the shop who had been sanctioned for a year, she tells me — “It’s inhumane to cut someone’s money off completely,” she says.

Latter doesn’t think taking away people’s belongings will help either. Last week a young man arrived at the shop asking for a sleeping bag after his was taken from the High Street. “It’s not solving the problems of the rough sleepers, it’s not dealing with their mental health problems, it’s not giving then somewhere to live, it’s just taking their stuff,” she says.

Bognor Regis, like everywhere else in the UK, has seen homelessness rise sharply in recent years. Since 2010 rough sleeping has gone up 169% across the country. A year-long project by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism recently logged the deaths of 800 people who died homeless between October 2017 and March 2019. A young woman names Louise Beddingfield was one of them. She had been sleeping rough outside Boots in Bognor Regis and was found dead at the end of 2017.

Local homelessness charity Stonepillow, which runs a hostel and day services in Bognor Regis, is already scaling back services in preparation for the funding reduction.

“We’ve had to start making cuts on our services, so we’ve had to look at how we run our provision and cut our cloth accordingly,” says Chief Executive, Hilary Bartle.

The hostel is currently full with a waiting list. Rough sleepers are prioritised for when a space next becomes available, but says Bartle, “there isn’t the availability of single person accommodation which is affordable and decent out there for people to move into, so the hostels tend to silt up a bit”.

To try and get more people off the streets over winter, Stonepillow worked with Arun District Council to extend their day service to offer beds overnight, but the extra services closed at the end March. Bartle says they saw more people using the service than the previous year, with between 16 and 20 people asking for accommodation every night.

Bartle points to welfare reform as a major reason for rising homelessness.

“We’ve seen a big increase since universal credit came in and the impacts of people losing their permanent accommodation because of delays in funding coming from DWP,” she says.

The introduction of universal credit, “is having a big knock-on effect because landlords won’t take the risk of taking people on benefits,” she adds. “Also there are delays in getting welfare benefits for up to five or six weeks, and then [people are] sometimes sanctioned.”

Mental health problems and substance misuse, whether alcohol or drugs, often plays a part in homelessness, meaning it can take time to build trust with people. “Severe alcohol misuse is often symptom of those who are rough sleeping because its a way of self medicating and coping with sleeping out,” Bartle says. Stonepillow tries to address the whole picture. “A lot of our clients come through with a whole range of mental health problems from minor anxiety right through to sort of major critical mental ill health problems,” Bartle continues.

But Bartle fears Stonepillow won’t be able to keep offering services after the funding cuts come in.

“None of us will know where we’re going to be next April,” she says. “We will probably have to go through some sort of competitive tendering process for services, [the councils] will specify what those services are and what they wish to purchase and commission”. A consultant has been hired to determine what the needs are.

All of this seems to have gone under the radar somewhat in the rest of town. Paul and the staff at Radio Respect knew nothing of the funding cuts and are shocked to find out.

Walter Wiltshire, a retired company director, who lives on the seafront and regularly sees homeless people camping in the beach shelters outside his house, says he feels a sense of despair over the current situation. “There has been no sort of human cry locally,” he says. “There were tents in the park recently,” he adds, “but they’ve been moved on now”.

Wiltshire started a petition asking the council to reverse the cuts to homelessness services. He hopes that as well as putting pressure on West Sussex County Council it might help to raise awareness in Bognor Regis.

“I have spoke to one person who is standing for the [town] council here, in the council elections in May and they hadn’t heard, they didn’t even know [about the funding cuts]” he says.

When asked for comment on the issues discussed in this piece, Paul McKay, West Sussex County Council’s Director of Adults’ Services, said:

“The council is committed to working with partners to support homeless people. Having to look to make savings in an area that supports a number of vulnerable people is not a decision we took lightly.

“But the county council is coming under unprecedented pressure to make savings, and we are having to make some really difficult decisions when it comes to our ever decreasing finances.

“The harsh financial climate means that the authority has to find savings of £145 million over the next three years in addition to the £246 million that have already been achieved and this is just one of a number of very difficult decisions that Members are having to make.

“In finding a way forward, a coalition of service providers, district and borough councils and the county council was formed to look at how services can be reconfigured to deliver a high level of outcomes to vulnerable groups on a reduced budget. As part of this we will be exploring alternative funding streams that can support these projects.

“After extensive consultation with stakeholders, customers and service providers the original decision to withdraw all funding was amended to a smaller budget reduction of £4 million over a two year period. This will allow a core budget of £2.3m to be retained from 2020/21 onwards to fund the County Council’s statutory responsibilities and to support key preventative services.

“In Bognor Regis, the county council and service provider Stonepillow were also successful this year in securing £188,465 worth of capital funding from Public Health England to improve services in the town.

“The funding will be used to redevelop and refurbish a purpose-built Resource Hub in Bognor Regis, open to rough sleepers, people who are homeless or those vulnerably housed within Bognor and the surrounding areas.”

Arun District Council said:

“When items are identified as being left, Council officers will make reasonable enquiries as to whether they have been abandoned before leaving a notice stating that it must be removed within 24 hours from the time of the notice. After 24 hours the items will be removed and stored for one month.

“If the property is deemed to be in an area where it could cause a risk to public safety, it will be removed straight away and stored for one month.

“Possessions can be reclaimed by the owner within this period by contacting Arun District Council.”