At least 50 people gave up a Saturday afternoon to discuss the fate of a former hospital in north London last month.

At a crowded open meeting, local people moved from one table to the next, giving their opinions on a housing development planned for the site currently occupied by St Ann’s Hospital in south Tottenham.

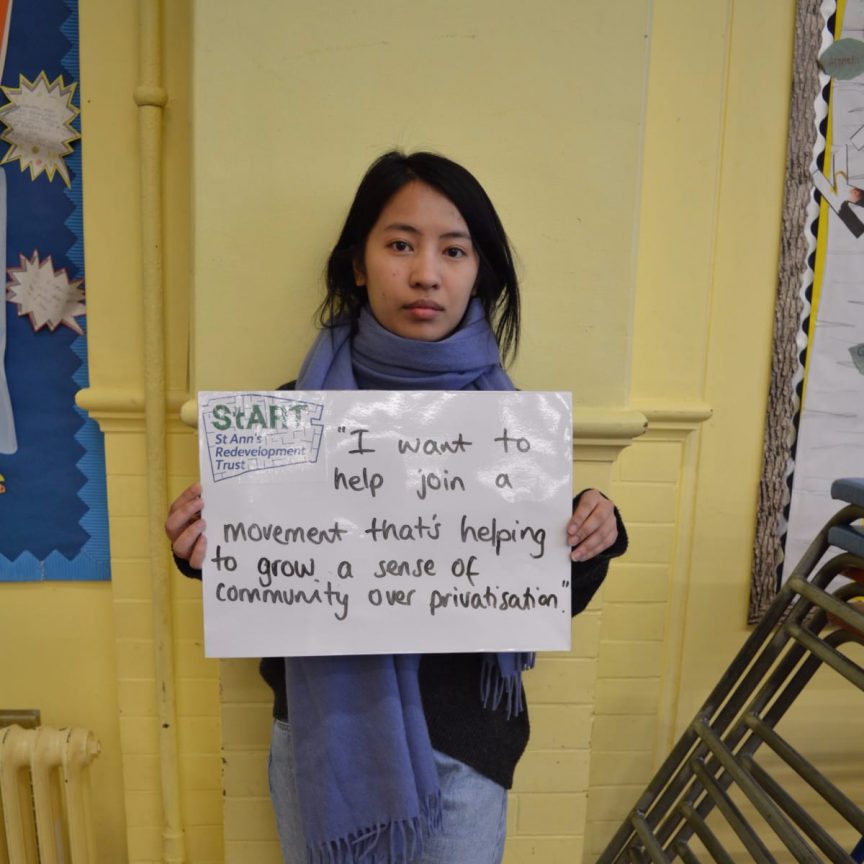

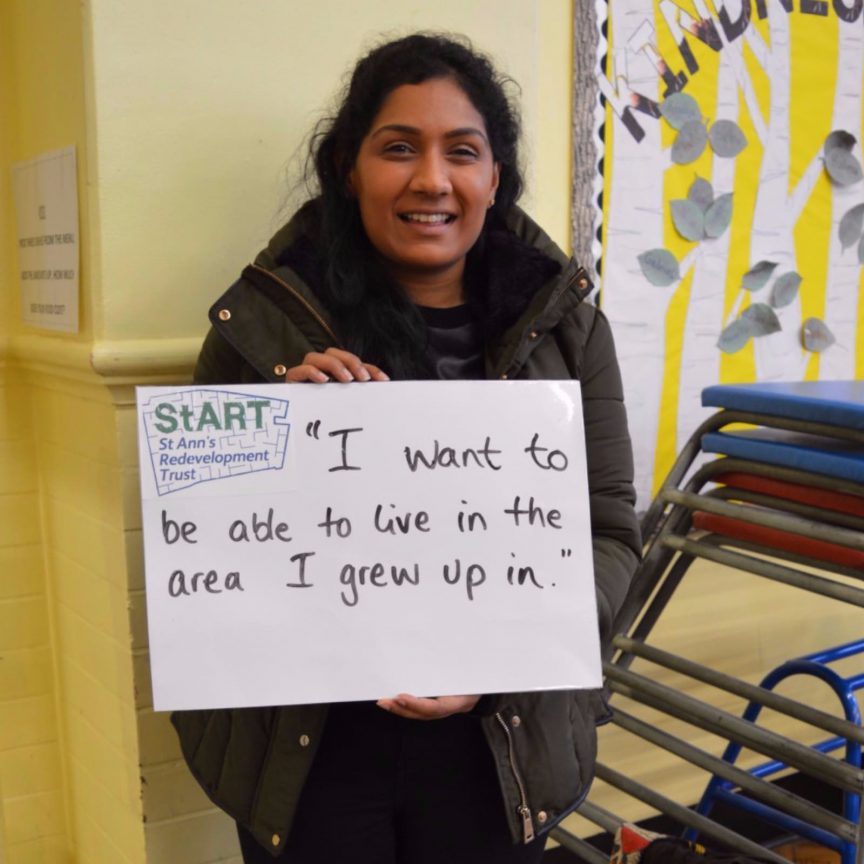

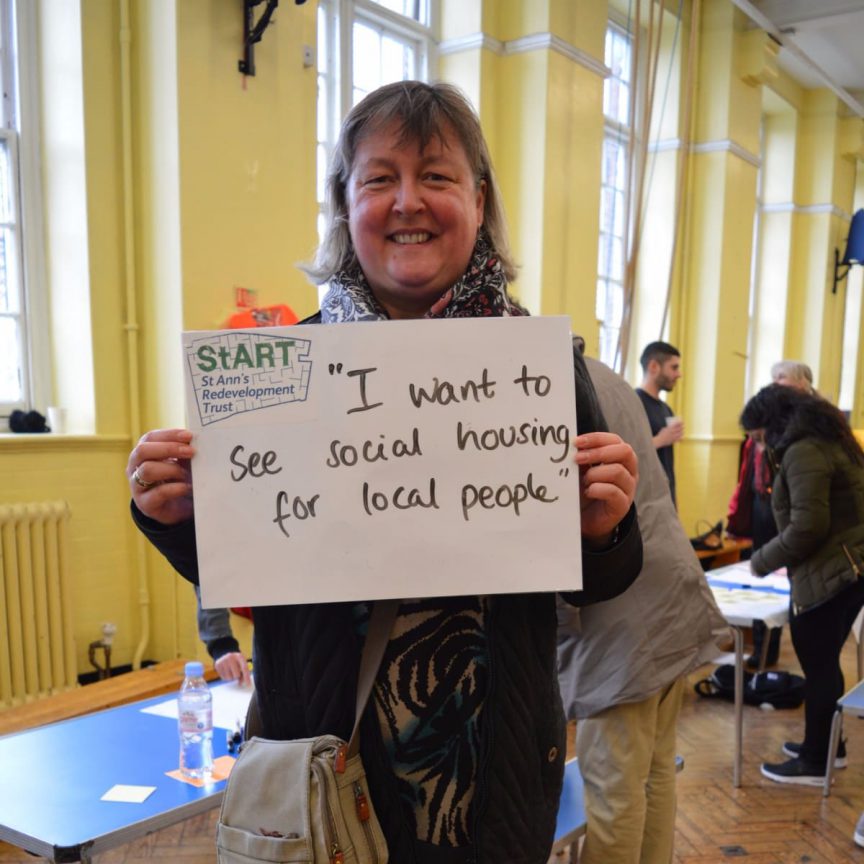

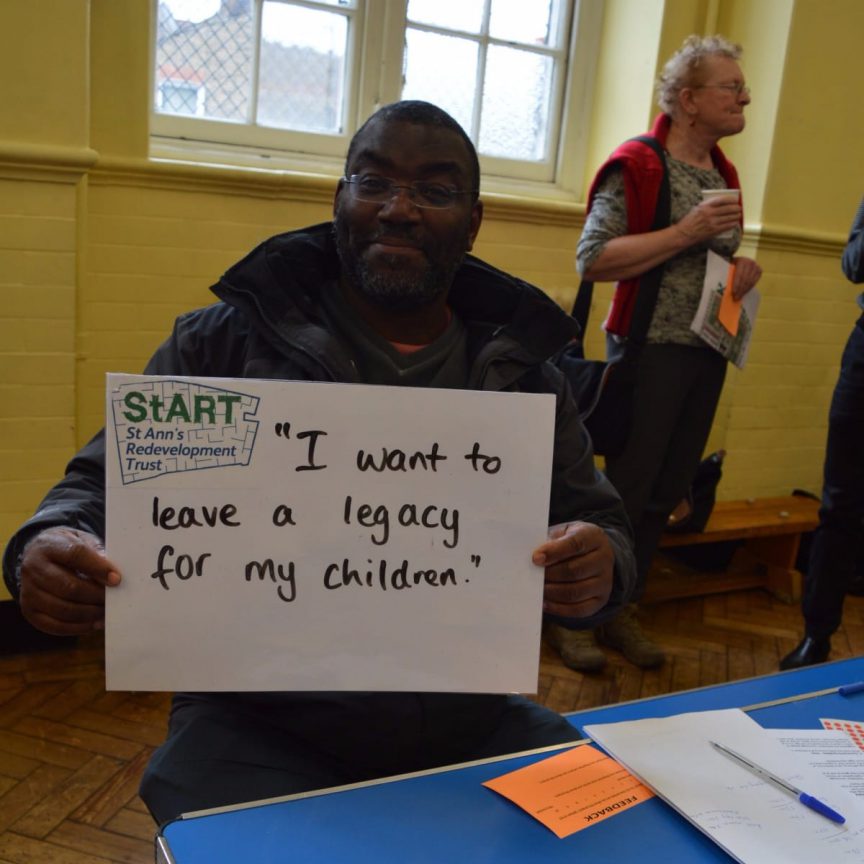

Brimming with ideas, attendees voiced their opinions on issues surrounding affordability, community control and environment, before eventually writing their thoughts on to posters on the back wall.

The meeting was the latest development in a five-year campaign to secure community-run and affordable housing on the unused site, which had looked set to sell to private developers.

Specifically, it was a consultation between the Greater London Authority, which bought the land from the NHS in 2018, and the St Ann’s Redevelopment Trust (StART), a community group which formed to fight for the site to be developed responsibly.

The GLA, which is London’s regional governance body overseen by Mayor Sadiq Khan, purchased the former hospital after intense pressure from StART to stop the site going to private developers, who planned to turn it into a housing estate where just 14% of properties would be ‘affordable’.

The GLA committed to working closely with StART, and the community consultation in April was to inform the requirements it says it will impose on private developers interested in the site.

At the meeting, two GLA staffers listened to community concerns and criticisms over four hours, patiently drumming out the party line.

But while the GLA officers said there “was a lot to be very enthusiastic about” in the requirements – pointing to a promise of 50 percent affordable homes – StART members did not seem enthusiastic.

“There was a clear view that the GLA have to do better,” Tony Wood, one of StART’s directors, told Novara Media after the meeting. “The general opinion of the people is it’s not good enough.”

StART wants 150 properties on the site to be community-led housing, meaning local people would play a meaningful role in the development and could ensure it fit local needs, but the GLA has suggested just 50. This isn’t enough, said Wood, and may prompt opposition from a community in Haringey well-versed in fighting planning applications. “Haringey is a toxic place for developers,” Wood said. “Having the community on side – which is what StART is trying to do – stops that toxicity.”

In addition to giving them control of 150 homes, StART wants developers to commit to between 65% and 100% genuinely affordable housing on site, while the GLA is proposing 50%, with shared ownership making up some of that.

“Shared ownership is not affordable,” said Wood. Two-bedroom shared ownership homes around St Ann’s rack up mortgage and rent costs of £1,600 a month, a figure well out of most Haringey residents’ budgets. 29% of Haringey residents earn under the London Living Wage and 48% have no savings for a deposit.

Negotiating iron-clad planning conditions ahead of a developer being solicited is critical, said Wood. “We’ve seen the same thing with developers in Haringey time and time again,” he said.

“The ’Spurs ground, for example. First, it was going to be 30% genuinely affordable housing […] And a year later, they went back and said, us as Tottenham Hotspur, who have millions of pounds, we can’t afford to do 30%, so we’re putting in revised planning permission with no affordable housing in it. And the local authority buckled and gave in.”

A spokesperson for the Mayor of London told Novara Media that they could not comment on the details of the requirements for the St Ann’s site for fear of prejudicing the procurement process. They said that “there are practical restrictions on what we can do, but through buying the site we can now require an absolute minimum of 50% affordable housing, almost all of which will be social rent or London Living Rent.”

Regardless of whether 50 or 150 community-led homes go ahead at St Ann’s, the development is on track to be home to the largest community land trust (CLT) in the UK. It is a flagship project for Khan, who has committed to greenlighting 1,000 community-led homes in the capital by 2021.

CLTs are a form of community-led housing where local people oversee the development of affordable homes and act as long-term stewards of those homes, ensuring they remain affordable in perpetuity. CLTs in England and Wales began in small rural towns, but have boomed in the last decade, according to Beth Boorman from the National Community Land Trust Network.

“The current affordability crisis is showcasing that just traditional methods aren’t cutting it anymore,” Boorman told Novara Media.

“What we’re seeing is that actually there are communities up and down the country that are experiencing crisis themselves, whether personally or whether it’s friends or family. […] Community land trusts are an idea that has appealed to lots of different people as a way of taking control and getting things done.”

Ten years ago, there were 14 CLTs in Engalnd and Wales. now there are more than 300.

Boorman added that StART’s efforts were “incredibly inspirational” given that the site was originally going to be redeveloped with just 14% affordable housing. “The community came together to say, no that’s not what this community needs. We can do something better.”

Boorman said that CLTs are typically smaller than the 150 homes StART is aiming for because “the concept is quite new to many of those in traditional decision-making positions”.

Initially StART wanted 800 community-led homes developed on site, but it subsequently scaled down its demands when it was told it lacked the expertise or credibility to run such a large project.

Wood pointed out the irony of politicians being frightened to adopt an innovative new housing model on the grounds that the existing system ‘works’.

“A lot of people are blinkered, [they say] that this, the way we are used to doing it, this is the way it works. But we all know the housing market is broken; there’s developers building houses, there’s poor doors and 20 per cent affordable. But they say, that’s the way it works. And we’ll carry on doing it that way.”

Khan has been a vocal proponent of CLTs, among other community-run housing models. In January, City Hall opened a £38 million fund for community-run housing initiatives.

But Wood is sceptical as to whether the Mayor will reach his target of 1,000 community-led homes without a more ambitious approach at sites like St Ann’s. “There is no way they will meet that target unless you do things on a much bigger scale at sites like StART and Camley Street in Camden,” said Wood. “Here, we have two very big bits of land where people want to launch community-led housing schemes. But where [is the Mayor] supporting that in a really positive way?”

Haringey Council did not turn up to the 13 April consultation event, despite being offered a table.

The local authority’s absence is significant because it sits alongside GLA and StART on the steering group which meets regularly to discuss the site.

A spokesperson for Haringey Council told Novara Media that while the “Council is certainly an important stakeholder in the project… this event was principally focused on StART’s priorities and its involvement in the scheme, and we took the view that Council presence wouldn’t add anything to the input from those present from StART and the GLA.”

Wood said that the group has been surprised by Haringey Council’s decision to keep its distance from the project after years of bad blood and publicity in Haringey over development – most recently with the development of Seven Sisters’ Latin Market.

“After Wards Corner, after the HDV, we thought – possibly naively – that you’d go to the council and say, here’s a huge news story for you. You work with the community, we can get you higher density [of homes], because we’ve been talking to everyone around the area,” said Wood.

Regardless of the outcome of negotiations, Wood is confident that St Ann’s will set a powerful precedent for community-run housing in London.

“START will take the bruises for community developments in the future,” he said. “We’ll push the door open, and we won’t get very much. But once the doors open a little bit, then the next one that comes along, they can say to the GLA, well you did it like this already…”

29/05/2019: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the local authority had a seat on the panel charged with selecting the site developer, while StART did not have this privilege. This was corrected to say that both Haringey Council and StART sit on the steering group.