How ‘Public-Common Partnerships’ Can Help Us Take Back What’s Ours

by Keir Milburn and Bertie Russell

10 July 2019

Over the last eight months a higgledy-piggledy north London market populated primarily by Latin American stallholders has become the scene of a pivotal moment in the trajectory of Corbynism.

It began with Haringey’s new ‘Corbyn council’ deciding to push ahead with a redevelopment scheme – led by building giant Grainger – which would involve the market’s replacement with a soulless, glass-fronted, mixed-use development, pricing out existing users. The decision met strong opposition from an alliance of stall-holders, market users and local residents. As Mirca Morera from the Save Latin Village campaign puts it:

“For too long, communities such as ours have been dispossessed by predatory development practices which – through programmes of ‘managed decline’ and outright bullying – prioritise profits over people to replace the cultural fabric of our cities with speculative property developments. We are fighting not just to defend our community, but to provide an alternative model for urban development which benefits low-income neighbourhoods across Britain.”

As the Save Latin Village campaign puts forward its own counter-plan for urban development, the case raises a problem central to left politics:

What role should social movements play in the production of public policy? And, conversely, what role should public policy play in cultivating the conditions for widespread social movements and an active citizenry?

Questions such as these are central to our new report on public-common partnerships (PCPs), published by Common Wealth. Taking the Save Latin Village campaign as one of our starting points, we propose a reversal to the familiar model of development in which public resources and community assets are transferred into private hands.

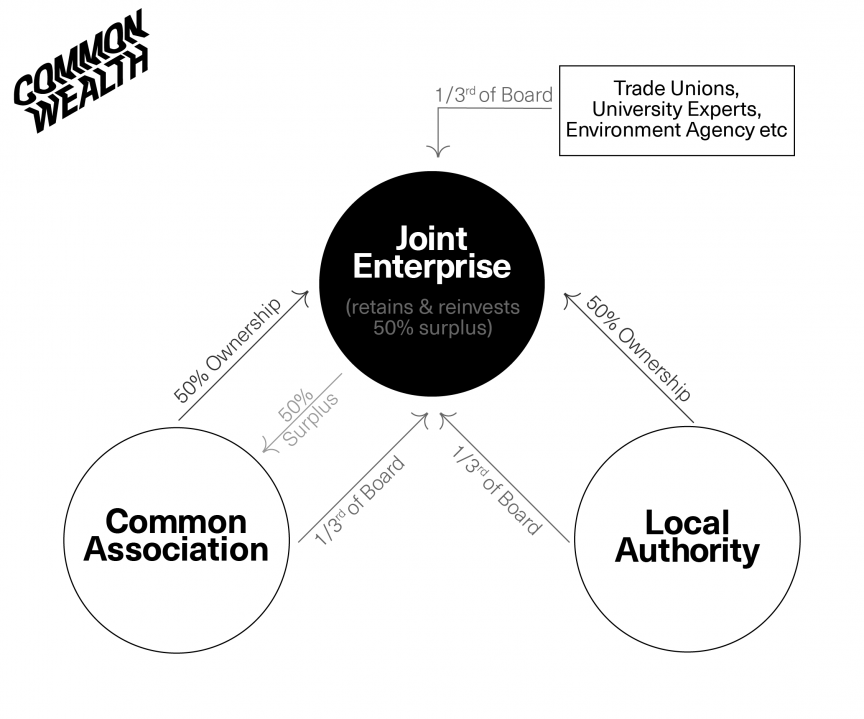

Instead, we see the opportunity for resources to move not just the other way (from private to public) but also from public to ‘the commons’ – not just collective ownership but a model which has decentralised democratic governance built into it. After all, commons can only persist if they are governed by a community of commoners. Public-common partnerships are co-owned and co-governed infrastructures – what we call a ‘joint enterprise’ – where the establishment of a common association is essential to making decisions and controlling resources autonomously from, but in partnership with, state authorities.

As the report explains, common associations – which may variably take the legal form of a consumer cooperative, mixed cooperative, or community interest company – have both the capacity and obligation to redirect surplus towards supporting and expanding other public-common partnerships. This helps to produce a self-expanding circuit of commons, bypassing the need for private financing and helping to sidestep the mechanisms through which finance capital exercises its discipline over the economy. Commenting on the proposal, Ben Beach – an architectural designer helping to present the Latin Village Community Plan – has suggested the situation in north London provides an “excellent opportunity for [London mayor] Sadiq Khan and Haringey council to demonstrate how a ‘public-commons partnership’ could work in practice.”

Importantly, public-common partnerships won’t come about solely through local governments passing policy. Whereas the politicians who pushed through public-private partnerships and private finance initiatives were in cahoots with a cadre of financiers who served to make a profit, public-common partnerships need a cadre drawn from social movements.

The role of social movements in the development of public-common partnerships is two-fold. First, as is already happening in the case of the Latin Village, social movements can force transparency onto opaque political and business decision-making, raising the political costs of ‘business as usual’ and helping to open up new political possibilities. Secondly, they can act as a catalyst for the formation of a common association, providing the initial lifeblood of any joint enterprise.

In the case of the Latin Village, the traders, market-users and residents of the Save Latin Village campaign could be the critical-mass needed to form the common association required to drive forward a public-common partnership. Mirca Morera says the concept of forming a public-common partnership “resonates with our ambitions to not just save the Latin Village, but to develop and expand this vital cultural hub for the benefit of both Tottenham residents and the wider community.”

The benefits of forming PCPs around crucial social infrastructure such as our markets will come to be felt far beyond the immediate users. As the expansive nature of PCPs leads to a more diverse and complex web of commonly-directed utilities and resources, we can increasingly guarantee collective and sustainable access to food, energy, water, housing and other basic human rights.

Given the obvious fact we all need these things to live, developing our collective control over them would strengthen our hand in more directly antagonistic forms of struggle. Strikes, for instance, become eminently more winnable when many of our life-support systems – such as energy, water, housing and transport – are commonly-owned and governed resources. Such a radical democratisation of ownership and governance functions as a ‘training in democracy’ while producing the stable material conditions upon which increased political participation becomes possible. It is a project of an ever-deeper democratisation of society.

As Beach argues, “breaking with neoliberalism will require new models for ownership and urbanism which – through bringing together local communities, municipal governments and socially-responsible experts – can ensure the benefits of urban development are democratically and equitably distributed towards meaningful social outcomes.” Public-common partnerships are one way of ensuring this break with neoliberalism in the here and now.