‘We are not nothing’: The Local Businesses Fighting Gentrification in South East London

by Thames Menteth-Wheelwright

12 August 2019

Huge change is set to transform the neighbourhood surrounding a major arterial road in south east London. Southwark council’s Area Action Plan promises to deliver thousands of news homes and jobs to the Old Kent Road over the next 20 years. Yet the regeneration of the area, which will turn large portions of its industrial land into high-rise tower blocks, will threaten hundreds of thriving businesses and jeopardise livelihoods. While development companies have already claimed stakes in the road, local businesses and residents are fighting for their right to have a say in the Old Kent Road’s future.

When Mark Brearley, a manufacturer and architect, formed Vital Old Kent Road (Vital OKR) in 2016 to represent the voice and interests of local businesses in the area, few people knew about the hundreds of manufacturers, makers and menders, and artists that populated the Old Kent Road in Southwark, South London. Tucked away behind the road’s nearly two mile stretch of cafes, hairdressers, chicken shops, and grocery stores are a huge variety of industries. Brearley’s business is one of these. Located at the far corner of an Asda car park, the very existence of his factory comes as a surprise.

Its large shed-like interior is a buzz of activity when Brearley shows me around. “This is all metal work here, like bending and punching,” he says over the hum of machinery. “There’s polishing in there, here we do pressing and cropping. And these will be for an order,” he says arriving at a stack of ribbed marble trays. In this inner-city location, people are making things with hammers and vices and nails, and with each blow challenging London’s reputation as a ‘post-industrial’ city.

Kaymet has been manufacturing anodised aluminium trays, trolleys and hotplates in London for 72 years and moved to its current site on Ossory Road in 2015. The utilitarian and distinctively slick products, first produced in the basement of an Elephant and Castle radio shop, are today sent out to over 200 shops in about 40 countries. Kaymet has tripled sales in just five years and currently employs 12 people. As Brearley put it in a recent public speech: “The days of decline are over.”

Kaymet is not alone in its success. The Old Kent Road and surrounding area is home to a thriving economy, with close to 1,000 businesses providing work for more than 9,500 people.

A detour off the Old Kent Road into its industrial hinterlands reveals the diversity of its trades. Near Glengall Road, located beyond the grassy expanses of Burgess Park, are businesses that specialise in everything from office supplies, electrical goods, thermoplastic sheeting, large format and commercial printing, and cinema equipment.

Walk south east past Halfords and B&Q, crossing on to Verney Road, and you will pass the UK’s largest manufacturer of metal containers, a screen and t-shirt printing studio and William Say & Co., which makes tin cans and employs 500 people. These low-rise warehouses and industrial hangars are a world apart from the glass skyscrapers of the City that loom large on the horizon. On the Hatcham industrial estate at the south end of the Old Kent road is a scattering of arts fabrication businesses. In one of the light industrial trade units is a company that makes riding and ceremonial hats as they have done since the 1950s, and a studio that specialises in West End Christmas decorations.

Then there are the others: melt filtration machine manufacturers, knife makers and menders, a drain lining company, and a company which cuts marble. This is not to mention the 900 people across 40 local businesses who work in vehicle repair, garaging and hire. “Our diverse industrial economy is fully thriving, premises are fully occupied, and there’s more demand than supply,” Brearley told Southwark council in a speech in April.

However, this vibrant local economy could soon be gone. Southwark council has set a target of delivering 20,000 new homes and 10,000 new jobs over the next 20 years as part of its Area Action Plan for the Old Kent Road, along with extending the Bakerloo line from the Elephant and Castle down to Lewisham by 2036.

The plans will deliver sustainable growth and double the number of jobs in the area, claims the council. But many local businesses and residents are fiercely opposed to developments on the grounds that they fail to meet the needs of the already existing community. Vital OKR argues that manufacturing will be hit particularly hard: around 4.2m square feet of industrial accommodation will be destroyed under the proposals and will be replaced with less than half the industrial space that is currently there. This would force hundreds of businesses out of the area and threaten around 4,000 jobs.

The mayor’s draft New London plan lays out a strategy of “no net loss” of remaining industrial floorspace in the city. The capital will also soon find itself in a workspace accommodation crisis, according to the GLA’s recent estimates. Southwark council’s vision for the Old Kent Road not only ignores these concerns but violates current policy. It has already approved 13 planning applications that will result in a loss of industrial land, with 11 of these allowing for the development of large-scale residential accommodation on land designated for manufacturing.

These include the £600m Cantium retail park development on the existing Halfords site, with a 48-storey residential tower, and the Ruby Triangle project which will see an existing church building and small business units demolished to make way for four residential skyscrapers. In July the council approved another huge development on Malt Street at the north end of the road of 1,300 new homes with 11 new buildings up to 44 storeys. Developments along the road have already forced many local businesses and churches out. Vital OKR estimates around 650 jobs have been lost.

For Kaymet, which prides itself on its “made in London” seal, moving out of London “would be the equivalent of someone dying,” says Brearley. For others like Johnny Batten, co-director of Studio Make Create on the Hatcham industrial estate, being located just off the Old Kent Road is logistically important. Like many other businesses on the estate – which produce costumes for West End theatres, printing for offices or food for workers – Batten’s serves central London clients almost exclusively. “We do shop window displays and we often install at night, so it’s important to be close to where we’re going to be,” he explains.

Studio Make Create has around two years left in its current location until the team are evicted and their current building – once a Dualit toaster factory – is turned into residential and mixed-use space. Many neighbouring businesses have already been forced out, including two taxi garages, a printers and a set-builders.

Developer Aitch Group has allocated 2,000 new homes to the Hatcham industrial estate, following the recommendations of the AAP to create “mixed” neighbourhoods in which new and existing businesses will co-exist with new homes. But under these proposals only 30% of the estate’s industrial space will be protected. For Batten, this will be the fourth time in 10 years that he has had to relocate his business; three out of four of these moves will have been because of housing developments.

The need for more homes across Southwark is undeniable. However, with only 30 out of 86 of the new flats on the estate designated as so-called ‘affordable’, it seems unlikely that they will alleviate the desperate shortage in the borough. In areas such as the Old Kent Road with easy access into the City of London, high rates of demand make residential property more profitable than business accommodation and far more so than industrial accommodation.

The employment opportunities, on the other hand, that these sites provide are vital: many of those who work along the Old Kent Road are involved in manufacturing, production and heavy industries and live locally. Across London, 11% of jobs, or close to half a million people, are part of the production economy, while other industrial jobs make up around 3% of employment, or 110,000 jobs.

“Jobs in manufacturing provide a different route to employment and a different kind of employment to office or retail work. This diversity is critical when seeking to provide employment for all Londoners,” says Josie Warden, a researcher at the Royal Society of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce. “Without the right space and accommodation, manufacturing and other industrial activities in London will suffer,” she adds.

What has angered those who work in the area the most is Southwark’s failure to adequately consult small businesses about the proposals. “The council has been negligent,” Batten says. His business was missed on the council’s first employment census in 2015 and it took having to “fight the consultants” to get them to include his studio on the report.

Batten worries that many of the area’s smaller, creative businesses are slipping through the net. Other businesses in his building were missed because they don’t have their own front door, and many who rent desk space were not even considered.

Southwark council has said that its business survey was preceded by a letter which was posted to each business address in the area. “The letter went to the occupier, rather than the landlord or the tenant,” a spokesperson for the council has said. Yet Brearley claims that in the case of some multi-tenanted spaces, such as the V22 building, the council thought of the landlord as the owner occupier so few – if any – of the 50-odd businesses in the building were ever notified about a planning application that would cause them to all be evicted.

Other small businesses such as Gringa, an urban dairy that makes artisan Mexican style cheese, located under the railway arches that separate the Old Kent Road from New Cross Road, also claim not to have been properly consulted. While there are no current proposals for the dairy’s site, the arches have recently changed ownership from Network Rail to the arch company in a move that Kristen Schnepp, the dairy’s founder, fears will leave the space vulnerable to future rent increases.

Schnepp, also a local resident near Bricklayers Arms on the Old Kent Road’s north side, believes the council’s “excitement” for regeneration has overshadowed its ability to fully consider “the needs of the existing community”.

“Taking out the parking on the Old Kent Road Tesco – that’s a great idea when you’re thinking about urban regeneration but some of these communities use that as a major grocery store that don’t have a good bus service…as a community that has extreme economic deprivation in some places, more care needs to be taken.”

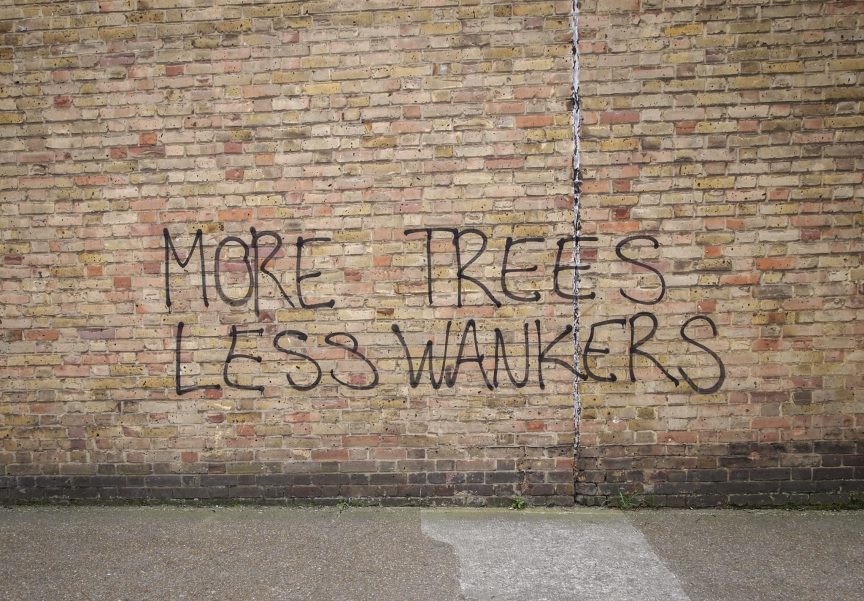

Schnepp supports Vital OKR but tells me it’s not just about businesses. “The council is ignoring the voice of our area,” she says. This goes to the core of the community’s problems with the regeneration plans: business organisations have a platform to stand on and express their concerns, but many Old Kent Road residents and community groups remain voiceless. Brearley reiterates this: “Who do you slaughter first? It’s obvious isn’t it? You slaughter the economic weaklings, the people without social capital.”

“The churches get hit, the car repair businesses get hit, they’re fragile businesses. They’re all local and they’re all from black and ethnic minority backgrounds. They’ve not been to Cambridge university like me.”

On a Sunday morning in spring a stream of people in brightly coloured fabrics enter an old industrial warehouse. Children in smart shoes and ironed shirts follow their parents through a glass double door; others arrive solo clutching handbags and linger outside. For the past 20 years, this building on the Old Kent Road, with its unremarkable and muted 1960s façade, has housed the Church of the New Covenant.

The unprepossessing building sits precariously on the edge of the Cantium retail park, which is due to undergo a multimillion-pound redevelopment into tall residential tower blocks. Although the proposal does not directly threaten the church, its approval sets a precedent for other large developments in the area.

The New Covenant Church is just one of many black-majority churches across Southwark. Research by Roehampton university suggests that Southwark has one of the biggest African Christian communities in the world outside of Africa. The study counted 240 African churches in the area; upwards of 25 of these are located along the Old Kent Road’s 1.5 mile stretch. Many of the churches are set up in modified ex-industrial buildings or old factories, where the leases are cheaper.

Their future is now uncertain. Like the Old Kent Road’s manufacturers, these churches are also threatened by Southwark’s draft AAP but unlike the area’s small businesses no organisation exists to publicly represent their interests. Many churches are being silently forced out of their premises. In the Ruby Triangle development, three black congregation churches have already gone.

Seyi, the Church of the New Covenant’s music director, tells me that many in the community already travel in from other parts of London so if the church moved location, the congregation would likely follow. “I live in New Cross, but we have people here who come to us from north London, some even drive in from Essex”, says Seyi. But for the church’s most vulnerable members, such as those who come from the old people’s home across the road, “it would cause great problems” Seyi says. “Lots of our community also live in council flats on the Old Kent Road, so our church is more accessible for them.”

To some extent the church’s location on the Old Kent Road seems of little consequence – the New Covenant Church has several other branches throughout London. What is significant, however, is the gradual expulsion of this community from housing in the surrounding area. Even if the church is not forced to relocate, regeneration of the area will mean that many of its local congregation will be pushed further afield by inevitably higher rents. This will undoubtably have the hardest impact on the church’s most fragile congregants, severing them from a community that acts as a lifeline.

Over the next decade the social and cultural character of the Old Kent Road is set to change. The African churches which coexist alongside industrial manufacturers, design workshops, artists’ studios, taxi-repair shops, warehouses for community groups by day and clubbers by night, its hundreds of makers, menders, chefs and crafts people, each contribute to a flourishing and unique local community.

Instead of being celebrated and helped to grow, the Old Kent Road’s businesses, churches and people face an uncertain future. However, thanks to Vital OKR’s outreach, recognition of their value is growing by the day. So, too, is their awareness of each other. And that in itself is small victory.

Thames Menteth-Wheelwright is a freelance journalist and an MA student at Goldsmiths university in London.