“What do you get when you cross a mentally ill loner with a society which abandons him and treats him like shit? You get what you fucking deserve!”

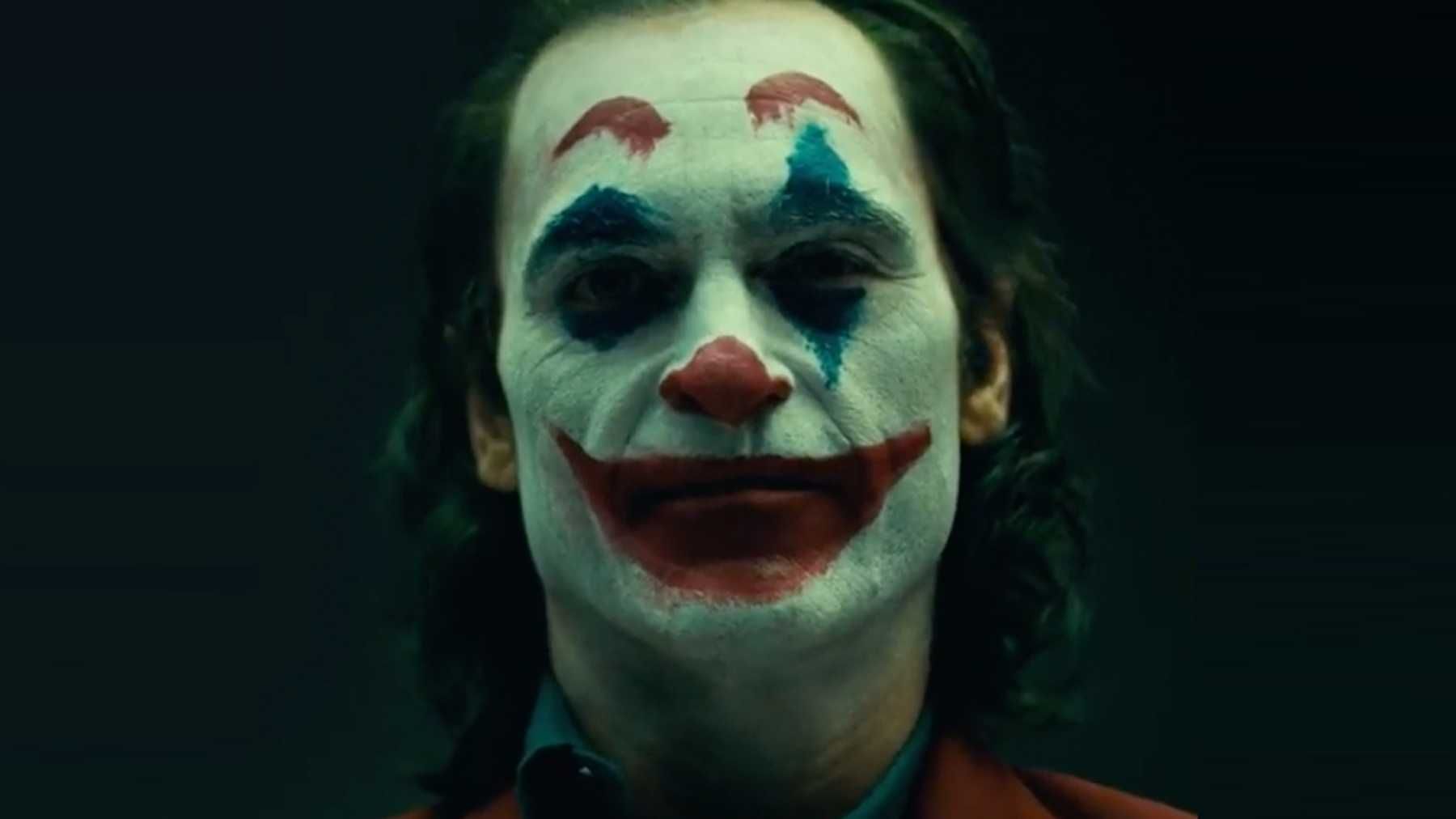

That is the frenzied provocation of Joaquin Phoenix’s creeping, skeletal Joker. Director Todd Phillips’ controversial new addition to Batman canon is visually startling and hypnotically tense – but not what you would call subtle. It parades its thesis aloft in triumph like the head of some vanquished enemy, skewered on a spike. Part origin story for the famous comic book villain, part rock opera of ultraviolence, it’s been called an unflinching masterpiece by some critics, and derided by others as simply a shallow and cynical handbook for incels. It’s neither.

It’s a story of villainy and revenge. But most of all, it’s a story about men’s unhappiness and the sickness at the heart of a society which heaps countless indignities upon them. It’s a film about how society suffers the consequences of its own failure, and it’s a plea for pity and understanding on behalf of frustrated lonely men who, in the quiet halls of their hearts, are planning terrible things.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that reactions to the movie have been polarised. We are in the middle of a huge cultural bunfight about how we deal with masculine misery – and who takes the blame when that misery sharpens and warps into violence.

Phillips’ villain, Arthur Fleck (Phoenix), starts off life as a standard-issue awkward and isolated weirdo with a less-than-standard catalogue of unspecified mental health issues and a pharmacy load of medication. Thwarted, emasculated and mocked by his colleagues, he trudges through the boredom of life as a low-grade clown for hire. He lives in a cramped flat with his mother and fantasises about life as a high-flying comedian, lived to the soundtrack of a crowd’s adoring laughter. Just one drawback: he’s chronically unfunny, totally out of kilter with everyone around him. He’s pitiable, but ultimately not a bad guy – he cares for his mum, he’s nice to passing kids. Unlike the suited, guffawing Chads he meets, he just can’t catch a break. Least of all in Gotham City, collapsing into filth and decay as the mega-wealthy party on in their concert halls and plush manor houses. We’re invited along the heady, gruesome spectacle as Fleck busts out of the routine in a spiral of escalating violence.

In some enlightened circles, it’s a pat aphorism that patriarchy has strongarmed men into stifling their emotions – that they’re quashed, ignored and derided. It’s true – but it’s not the whole truth. It sometimes eclipses the fact that white men’s everyday boredom, everyday misery and everyday anger are treated as a matter of civilisational crisis, not least among the ranks of the new alt-right.

Likewise, our political landscape is haunted by the spectres of men who lash out vengefully on the society that has supposedly done them wrong. Loners, misfits and madmen, we’re told. It’s tempting then to draw a straight line from suffering to violence which writes over questions of blame and agency – questions of why they are suffering in the first place, and who should be held accountable.

This isn’t the first Joker origin story to sympathise with its villain, and many a great story has been told about the descent of ordinary people into extraordinary cruelty. Humanising villainy isn’t a problem; indeed the shock of the familiar in the despicable is vital to reminding us of our own implication in horrorshow systems of everyday violence. It’s uncomfortable – and therefore important – viewing. But it speaks volumes that in this film Joker’s descent into brutality is triggered by such a flimsy, workaday series of events.

Arthur Fleck feels ground under the boot heel of an uncaring city, a dead-end job and an utter lack of the public adulation he craves. Meanwhile, society is collapsing around him into malaise and decadence. In the first scene he’s beaten up by a gang of BAME teens. He resents being surrounded by a bevy of tedious paper-pushers gatekeeping the state bureaucracy (most of whom are black). The rich are rich, and this is bad because these rich people are bad people, the movie tells us. Nothing is being done to help the little guy. “No one is civil any more,” complains Fleck. Filmmaker Michael Moore has taken this as a revolutionary diatribe against the malaise at the heart of our system which produces mass shooters.

But Joker isn’t produced by the world around him. There is no connection between the ill-defined political unrest the movie vaguely swipes at and what makes this villain a villain. Rather, the movie makes a hazier connection that society must be bad, because it fails to grant Fleck respect, because it fails to grant him power, because it fails to adore him. There must be something deeply wrong with the universe. Scores of alt-right YouTubers and MRA controversialists would agree.

This yawning disconnect makes for a movie distinctly more stupid than its fans or many of its critics give it credit for (despite a barnstorming performance from Phoenix). It deploys the feeling of the political with no real direction or purpose. Joker becomes a symbol of nebulous resistance – against, well, something I’m sure. It really makes you think, we live in a Society. But this grinning incoherence lets it slides neatly into an alt-right world picture; diagnosing civilisational downfall but offering no change, apart from a restoration of personal dignity through violence, from the nihilist thrill of fucking the system right back. It’s a template for a contemporary fascist imaginary which mistakes ordinary alienation and unlaundered narcissism for oppression, whose riot optics mistake raging against the machine for raging that you’re not part of it – that your birthright has been snatched from your grasp.

The alt-right have an explanation for the white man’s unhappiness; it’s because the natural order was overhauled by women, black people, decadent elites. That order must and will be restored with violence, to regain your power and dignity, to claw your way back into heaven at any cost. The movie and the alt-right share this fixation with a vapid spectacle of violence as a cipher for change.

But women are angry too. BAME people are angry. Migrants are angry. And working class people, and men without tendencies towards bloodthirsty rampage. We are angry too, and bored, and isolated. We too watch dreams disintegrate. We are alienated and trapped in the technocratic nightmares of an uncaring state. Yet none of it is treated as cause for alarm. None of it would count as a sufficient backstory to humanise a turn to violence. Because we were not promised happiness. We were not promised power or dignity or respect. So why should we be outraged when the world denies us what it never promised?

We too have our problems. Largely they are treated as a sign that society is ticking along nicely. To bastardise Margaret Atwood: Men are scared women will not laugh at their jokes. Women are afraid men will kill them.

Notorious incel Elliot Rodger was angry and sad when he gunned down six people in 2014. So was the El Paso shooter, who took 22 lives. Their manifestos tell us so. In both cases their misery was first on the list of explanations, along with their social isolation or their presumed mental health issues. We called their actions tragic, we called them monstrous and unspeakable. But we also wondered whether the redistribution of sex or stricter border controls might prevent such tragedies from happening in future. That we as a society should rectify the stated cause of their unhappiness as soon as possible. Their rage is treated as premiere politics; analysis, motivator and theory of change all in one.

Joker is mad, sure, the movie gauchely tells us, and of course he goes too far – but is he wrong to rail against a society so nakedly (if non-specifically) corrupt and broken? Like a fool in a Shakespeare play, his madness simply unshackles him from the bounds of normality so he can see with more clarity and urgency how broken our normality really is. We have no choice but to sympathise when he starts to take matters into his own hands.

I’d love to say that this movie is an ironic condemnation of an incel psyche if it weren’t trying so desperately to convince us that Joker is absolutely right to hate on society, man – and if the director hadn’t launched his own invective about being victimised by ‘woke culture’. If Joker existed in our reality, he would have a Netflix special called something like ‘Trigger Warning’. And I might be tempted to call the film an alt-right handbook if it didn’t take such pains to paint Fleck as gross and pitiable, and the riots he incites as unwashed plebbery (although it should be said that blackpilled incels are the first to volunteer themselves as contemptible).

In truth, it’s something more chilling. A confessional for a culture which disowns the violence of white men – whilst endlessly forgiving it, endlessly excusing it, and endlessly placating its demands. A society which harbours the suspicion that men must be appeased with power or they will take it by force. A perfect framework for reinforcing patriarchal norms under the guise of humanistic sympathy of those bereft and left behind by a world which should ordinarily care for them.

Joker the character is contained in pages and screens – and if you shut part of your brain off, Joker the film is a tense, multicoloured revenge romp with a chilling lead. But the culture which made Joker possible, made him sympathetic, made him adored – that is right here. I know a villain when I see it.