The West Midlands Mayoral Row Comes Straight From the Labour Right’s Playbook

by Aaron Bastani

23 October 2019

Last week Labour’s NEC shortlisted three candidates for the party’s West Midlands mayoral nomination – Liam Byrne, Peter Lowe and Salma Yaqoob.

Byrne is probably the best-known candidate. At the end of his tenure as chief secretary to the Treasury in 2010 he decided to leave a note for his successor, the Liberal Democrat David Laws. In it he cheerily declared that the government purse was empty, “I’m afraid there is no money.” A misplaced attempt at humour, those words would not only haunt Labour for the next five years, but also furnished a veneer of legitimacy on the coalition’s programme of public sector cuts.

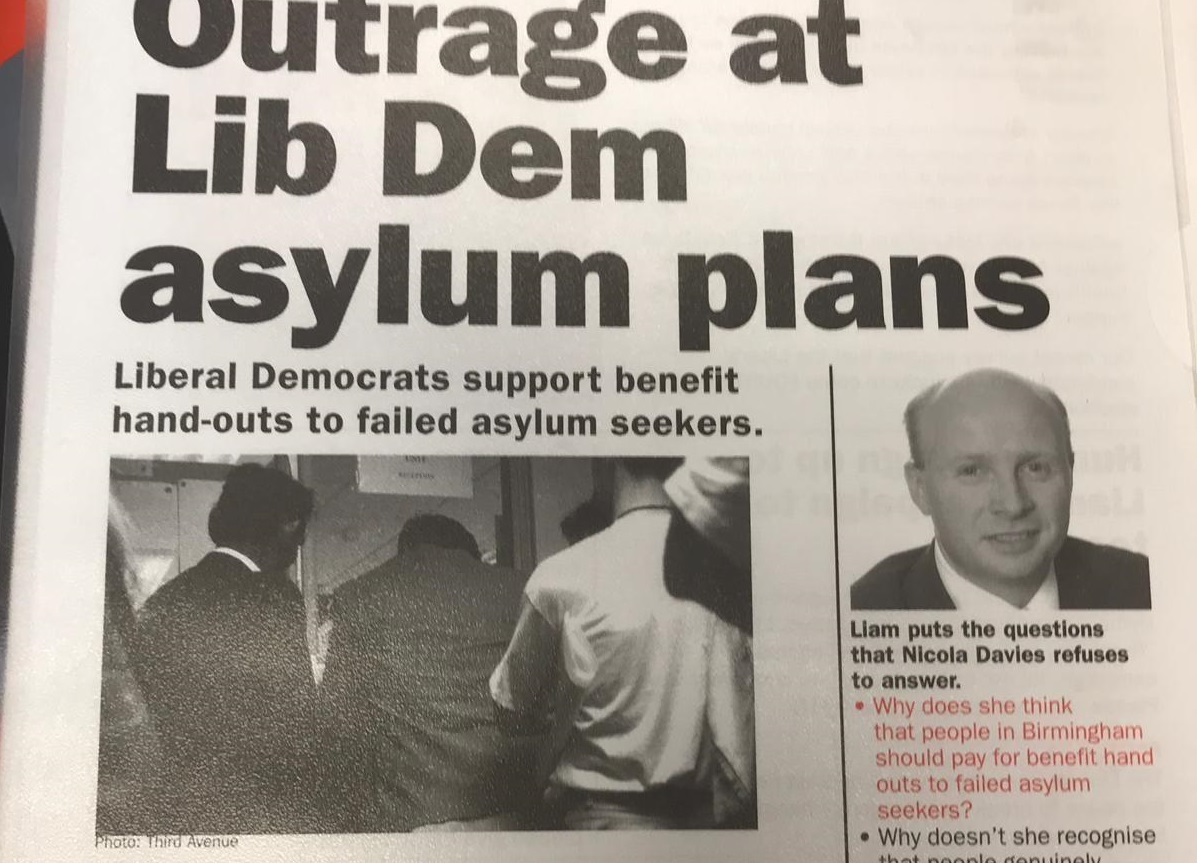

Less widely known, but an issue for much of the party’s membership, is how Byrne, while contesting the 2004 Hodge Hill by-election, participated in one of the most racially charged campaigns in living memory. One leaflet, which Byrne claims to have never seen or distributed, had the headline, “Liberal Democrats support benefit handouts for failed asylum seekers”. Other campaign literature peddled the kind of rhetoric one would intuitively associate with the alt-right, such as lamenting the involvement of 16-year-olds in the production of pornography and the prospect of people purchasing cocaine over shop counters. One leaflet, depicting nothing but a cross of St George inscribed with the words ‘Labour’ and ‘On your side’, captures the bleak vacuity of the mature Blair years – the optimistic project of the late-20th century long forgotten.

While Byrne was fighting that campaign, having previously enjoyed a career in finance and consultancy, Salma Yaqoob was fast becoming a prominent figure in Britain’s anti-war movement. Politicised by the ‘War on Terror’ she threw herself into activism, eventually entering electoral politics with the Respect party. In the 2005 general election she contested Roger Godsiff’s seat of Birmingham, Sparkbrook and Small Heath. There she finished second to the Labour candidate amassing an impressive 27% of the vote. Labour garnered just 9.5m votes that year, 3m fewer than Jeremy Corbyn in 2017, and the lowest tally in modern history to form a majority at Westminster.

Byrne’s career in government – while perhaps briefer than anticipated – was eventful, with the energetic MP elevated to cabinet within 12 months of taking his seat. These, however, were the dying embers of New Labour, a period defined by an absence of political vision and a slide into authoritarianism. When Tony Blair’s successor, Gordon Brown, gained just 29% of the vote in 2010 that was presumed by many to be the party’s nadir. Yet five years later, under Ed Miliband, Labour fared little better, losing 40 of its 41 seats in Scotland.

Like so much else in Labour, the elevation of Jeremy Corbyn in the months following Miliband’s defeat changed everything. Yaqoob, while not yet a member of the party, helped organise the first leadership rally for Corbyn in her native Birmingham. Byrne, meanwhile, nominated Yvette Cooper. Yaqoob has told me that she subsequently applied for party membership during this period but was repeatedly blocked. On the one hand that is understandable – after all she had run against Labour in an election just a few months earlier – but on the other she had been a prominent figure in Stop The War, an organisation of which Jeremy Corbyn himself was then chair. The congruence of the politics between the two, on war abroad and austerity at home, was inarguable, yet Yaqoob’s admission was not allowed until 2018.

Less than a year into Corbyn’s leadership, Byrne was one of 172 Labour MPs to back a motion of no confidence in him, the intention being to force a resignation. In the race that followed Byrne supported Owen Smith, a man whose chief political strategy transpired to be giving away ice cream. That lack of political acumen shone through again when, the following year, Byrne worked on the ill-fated Siôn Simon campaign for West Midlands mayor. Despite Labour enjoying a majority of MPs in the region – including nine out of ten in Birmingham – the Conservatives’ Andy Street triumphed in a surprise upset. In the final weeks of the campaign Simon disowned his party leader, something he repeated on the night of the vote, declaring that the national party was ‘out of touch’. A month later Labour recorded its best general election result since 1997.

Accounts I’ve heard regarding the campaign tell a story of professional incompetence and political vacuity – of a disintegrated former elite bereft of ideas, policies and purpose. As one activist put it to me: “They had no real policy or strategy, their overriding thing was hating Corbyn…they just presumed he would be gone soon.” And yet, as we now know, he wasn’t, and just as his detractors were confounded during the previous year’s ‘chicken coup’ the same applied now – only to a far greater extent.

For an ambitious politician like Byrne this posed a problem. After all he had aspirations to contest the mayoralty the next time round, hoping the process would resemble a coronation with no real rival. It was during this period that the Hodge Hill MP gained the endorsement of John McDonnell, causing uproar among the left locally, especially BAME activists. After all, McDonnell – for so long an outstanding tribune of the party’s membership – had backed the very person who coined the term ‘hostile environment’ and in one of the country’s most multicultural regions.

When Yaqoob announced her intention to stand a month ago many were pleased. After all, she is a local candidate, has a strong political track record and would be the first woman to be elected as a Labour mayor. For all the talk of empowering women and minorities, however, she was soon subject to an avalanche of political attacks – labelling her homophobic, misogynistic and unsuitable given she fought an election against Labour as recently as 2017. Although the last claim is an important one, and was something I raised in a recent interview with Yaqoob, the other two are confected lines of political attack. Indeed in a recent recording, published by the anonymous fake news outlet ‘Red Roar’ (alleged to have close ties to the right-wing Guido Fawkes site) apparent ‘evidence’ of Yaqoob’s homophobia actually concluded with her saying “being anti-discriminatory as a Muslim is a no brainer”.

Elsewhere, Naz Shah has accused Yaqoob of running a campaign of ‘misogyny, patriarchy and clan politics’ against her two years ago. The evidence for this is threadbare at best. Yaqoob is a capable woman and NHS psychotherapist, but because she wears a hijab reflex attacks of sexism and homophobia are more likely to stick. This, sadly, is the reality of Muslim women seeking public office – something I also observed with Rabina Khan when she stood for Tower Hamlets mayor four years ago.

Efforts to isolate Yaqoob are straight from the handbook of the Labour right – from the distribution of attack lines to third parties, like Red Roar, to claims regarding her moral standing, and the seemingly autonomous ‘interventions’ of other MPs. Such a strategy aims to erode Yaqoob’s ability to fight a propositional campaign through keeping her on the back foot. This is how Labour’s old establishment polices the boundaries of political legitimacy, the terrain of actual politics assiduously avoided. Why? Because if that is where the selection is fought Byrne will lose.

Such efforts are clearly coordinated and well-resourced and given recent escalation – Shah has started a legal case to have Yaqoob disqualified, and this week published a soft focus video – the question must be asked: who is footing the bill? When I put that question to Shah she declined to comment.

Importantly, identical tactics were deployed when local BAME activists questioned Byrne’s record on race and immigration. Having raised this at a local event, Byrne left without giving a response. Later, when a statement was posted online regarding similar misgivings he privately threatened to sue for libel. When I asked Byrne if he had pursued that threat, or if he had any relation to the legal case now being actioned by Shah, he did not comment.

What is most revealing about the Byrne campaign is this: a politician who has, in his defence, supported the leadership since 2017 is unable to account for, or even admit, past mistakes. What’s more, the efforts to have him nominated, powered by the party’s right and four years into the Corbyn leadership, aren’t being fought on polices and ideas but slander.

Whatever the outcome in the West Midlands, this should be of concern to anyone who cares about Labour, and indeed the future of British politics. It would indicate that the political default of Byrne and his fellow travellers remains broadly unchanged since the notorious events of 2004.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media co-founder and contributing editor.