Why Are University Staff Going on Strike? Here’s What You Need to Know

by Oliver Eagleton

24 November 2019

From Monday 25 November, staff at 60 UK universities will walk out for eight days of strike action. Their decision, which is likely to affect over a million students, was prompted by two separate disputes: changes to the pension scheme, and declining pay and conditions. Yet the implications of the strike are broader. After years of compromise by the University and College Union (UCU), it marks a decisive pushback against the marketisation of higher education – a programme which has destabilised the sector, made staff workloads untenable and sent academic standards into free fall.

The attempts by successive governments to turn universities into instruments of big business are well documented. In 2009, Gordon Brown handed responsibility for higher education to the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, hoping this would increase its receptivity to market interests. The same year, he established a seven-person committee – including a former BP chief executive, a conservative economist and the head of a multinational bank – tasked with deciding the future of the sector.

Their recommendations formed the basis of Tory-Lib Dem policy: tuition fees rose beyond £9,000, recasting students as consumers; departments which did not teach market-friendly subjects were drained of funding; and cash-strapped universities were forced to compete with one another for students, pouring millions into marketing while slashing academic budgets. At the same time, private investment in higher education soared, with the state giving lavish subsidies to low-quality profit-making universities.

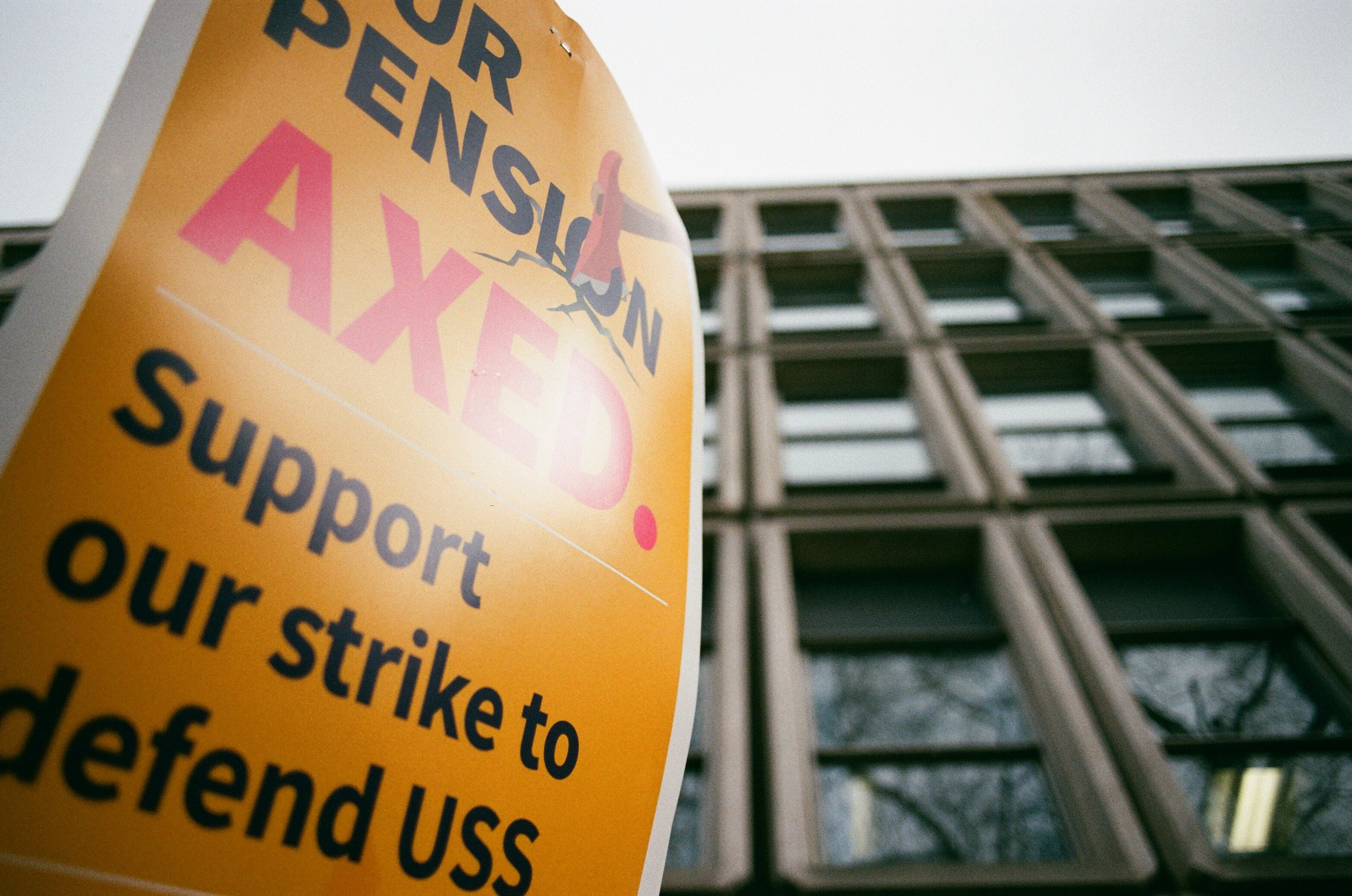

Throughout the coalition reforms, many staff members resolved to save their energy for an inevitable fight over pensions, which finally arrived in 2018. Until then, the universities superannuation scheme (a private pension plan which covers most higher education institutions) ensured that, whatever the cuts to their departments, academics could at least retire on a reasonable income. As such, it represented one of the final obstacles to university privatisation, since potential investors would be put off by the high cost of the pension plan. So, in 2018, the employers’ association Universities UK set about destroying it.

Citing a £17.5bn deficit in the USS fund, Universities UK proposed securing the plan’s financial viability by switching from a ‘defined benefit scheme’ to a ‘defined contribution scheme’. In practice, this meant that a fixed annual income would be replaced by a variable pension payment tied to the performance of the stock market. As Jamie Woodcock explains: “The proposal by the employers was to move from a guaranteed deferred payment of wages in old age, to a guaranteed contribution into a pot with which managers of the fund would gamble on the market, while staff kept their fingers crossed for a good outcome.” Were the outcome not so good, bosses would bear no responsibility for saving their retirees from poverty. An independent report found that a typical lecturer would lose £10,000 per year under this arrangement.

The UCU balloted for strike action in January 2018, returning a vote of 88% in favour. What followed was the largest industrial action in British higher education history, as 42,000 workers withheld their labour for fourteen days. Students joined lecturers and other university staff on picket lines across the country, and draconian strike-breaking measures – such as the threat to dock staff wages – were defeated by alumni solidarity initiatives. Meanwhile, the USS valuation which had uncovered the supposed £17.5bn deficit was proven to be bogus – a financial scare story based on “incomplete calculations of asset performance and contributions”, according to research by union representatives.

In March 2018, despite popular support for the strike and growing militancy amongst the UCU rank-and-file, the general secretary at the time, Sally Hunt, unexpectedly endorsed a deal which would have cut staff pay in exchange for a temporary retention of defined benefit. Union members – dismayed at this capitulation, and outraged at the leadership’s unaccountable negotiating style – voted down the proposals. But by that time the summer vacation was looming, and doubts about the efficacy of a continued strike convinced staff to postpone the confrontation. They agreed to set up a joint expert panel, composed of UCU and UUK delegates, which would complete another USS valuation and draft new proposals in late 2018.

Those proposals have been roundly ignored by employers, and by the USS itself. The panel determined that there was no legitimate reason for employee contributions to rise beyond 8%, yet a rate of 11.7% is set to be imposed on academics next year. Far from ensuring the solvency of the scheme, this change threatens to unravel it completely. Academics’ wages have already fallen by a staggering 20.8% over the past decade, with the median hourly rate for many lecturers now at £9.35. A significant number of staff may therefore opt out of the scheme rather than pay increased contributions, creating a real funding crisis rather than a concocted one. If this fast-tracks the dissolution of the USS, that may suit employers just fine: last year, a leaked UUK document revealed that university bosses are considering the breakup of the scheme as ‘radical option’ to overcome UCU resistance.

When workers abandon classrooms, labs and libraries tomorrow, they will call for the implementation of the panel’s suggestions. But their demands do not stop there. They will also be campaigning for an end to casualisation. According to the most recent figures, 46% of universities and 60% of colleges use zero-hours contracts to deliver teaching. The use of fixed-term contracts and short-term funding arrangements is even more prevalent, leaving academics with no sense of whether they will keep their job from month to month. As well as targeting these exploitative practices, the UCU is fighting for a 3% pay rise, the closing of discriminatory pay gaps, and limits on excessive workloads (higher education staff work an average of more than two unpaid days each week).

Local strikes in the academic sector have already had remarkable success. Earlier this year, staff at Hugh Baird College forced the management to institute a 6% pay rise and new annual leave days; Bradford College agreed to move hourly paid staff onto permanent contracts; and a long-running dispute at Nottingham College ended with the college guaranteeing workload protections and dropping a proposed pay cut.

Unlike in 2018, UCU now has a radical and effective grassroots leader, Jo Grady, who is determined to take on the employers. The union also has a wider constituency this time around, with university cleaners and caterers joining the battle against casualised labour. Their action falls in the middle of a general election campaign which could decide the future of higher education for years to come. Will staff continue to struggle against privatisation, or will they get back to working under a free and fair system? Will their sector be populated by producers and consumers, or by teachers and students? Both Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour and Grady’s UCU want a future in which education isn’t a commodity. It’s up to us to realise it.

Oliver Eagleton is an editorial intern at New Left Review.