We Need to Change the Way We Talk About Climate Breakdown. It Shouldn’t Be This Boring

by Adrienne Buller

29 November 2019

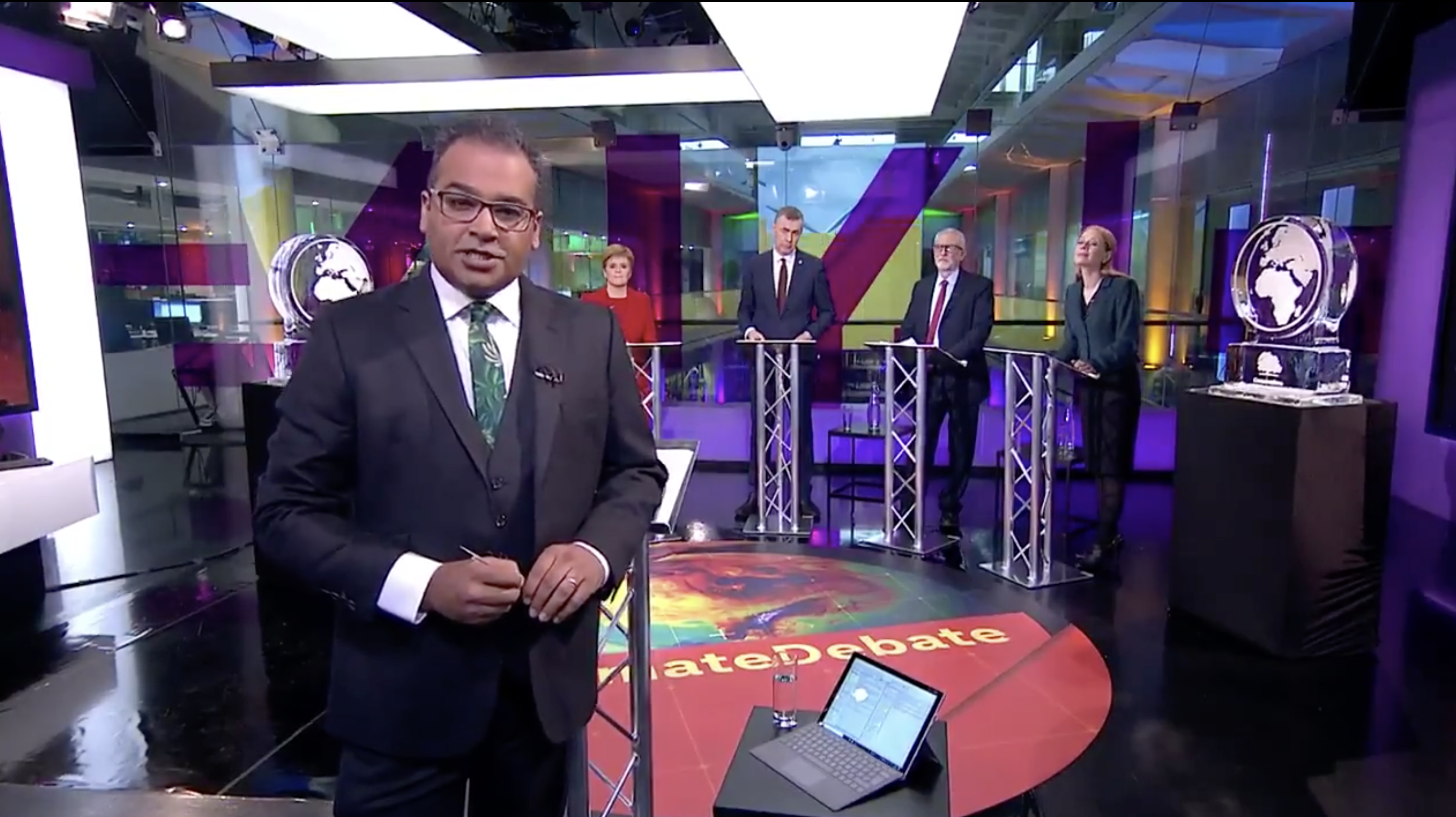

The first ever televised leaders debate on climate change happened on Thursday night, with eager audiences gathering to watch it together at viewing parties around the country. At one such event in London, in a Q&A after the screening, an audience member asked, “who do you think, really, we brought on side with that debate?”

The implicit answer was clear: no one. And lamentably, I agreed. In nearly an hour of debate on the defining issue of our time, discussion ranged from grass to electric heat pumps to reusable nappies to hedgehog populations. The questions were overwhelmingly technocratic, with too much time spent on issues like food production and plant-based diets, levies on international aviation, energy efficiency and gas boilers. It was – dare I say it – boring.

Worst of all was a concluding segment on leaders’ pledges for personal behavioural change. The problem with this final question could merit an article on its own, but to be brief: to focus on personal responsibility for climate change is both to use a device of the fossil fuel industry and to create a smokescreen for the real conversations that must be had about tackling the climate crisis. Certainly, we should all try to live more sustainably and to be conscious of our personal impact on the environment, but the devotion of five minutes of the first ever climate debate to this puerile question underscores the same issue underlying the debate’s dry, technocratic content: quite simply, we are terrible at talking about climate change. We must get better at it immediately, or face the consequences.

In much the same way that few people outside the think tank circuit are particularly inspired by the revenues that can be raised from proposals to tax wealth equivalently to how we tax income, no one who isn’t already concerned about or active in tackling climate change will find themselves galvanised by detailed plans for replacing millions of boilers by 2030. And so last night’s debate will have spoken to very few people beyond those who already embrace the urgency of this crisis.

The problem is, with climate change, as with economic issues, we continue to avoid the critical question: why?

Why is climate change happening? Why can the government afford to borrow billions of pounds to invest in the future, when I can’t afford my heating bill, let alone a mortgage? Most of all, if we know what the problems are, why is it all taking so long to fix? The ‘why?’ is the question that must be asked in any serious debate about the climate crisis.

The answer is simple: we exist under the yoke of an economic model that is unstable, extractive, and exploitative of both labour and nature by design. Climate breakdown is a product of the same destructive economic logic that has pushed 14 million people in the UK into poverty, driven record waiting times in A&E, and left the working people of this country overwhelmed by private debt.

Climate change is a class issue, it is an economic issue, and it is therefore profoundly political. To avoid treating it as such will doom us to failure in our efforts to confront it. There are solutions that address the issue in this way – Labour’s Green Industrial Revolution is borne of the recognition that climate, environmental and economic crises cannot be tackled independently. And it offers solutions that will deal major blows to emissions while improving people’s lives with warmer homes and lower energy bills; good, green, secure jobs; preservation of the natural systems that communities cherish and rely on; and an economy that doesn’t place the costs of the profligacy of a wealthy few on to those who have contributed the least to the crisis.

This is election winning policy – but not because it is fully costed and accompanied by detailed, pragmatic and implementable plans (though, it is). The way in which the ‘credibility’ of Labour’s manifesto is held to such an extreme degree of scrutiny relative to other parties proves that some narrowly-defined credibility is not the real issue at hand. The Conservatives know this – it’s why they didn’t even bother to show up to the debate.

The Green Industrial Revolution is election winning policy because it correctly identifies the root causes of the problems we face, and proposes a way to tackle them with a vision for a better, fairer, kinder society.

This is how to tell the story of climate change, in debates and on the doorstep. Every solution – no matter how technical or abstract the problem – is political, and in deflecting rightwing attacks, the left must not end up playing the right’s game. At the same time, the left must not revert to talking about climate breakdown in the language of middle class environmentalism either – territory into which last night’s debate frequently strayed – not least because this narrative obscures the history of communities of colour in the global south and indigenous peoples throughout the world who have constantly been the vanguard of this fight.

This election is a historic opportunity with tremendous consequences. Labour has the policies and the plans, but it needs to get better at telling the story.

Adrienne Buller is policy director of Labour for a Green New Deal.