‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ Services Are Normalising Debt for a Generation Who Might Never Have Mortgages

by Jack Palfrey

30 March 2020

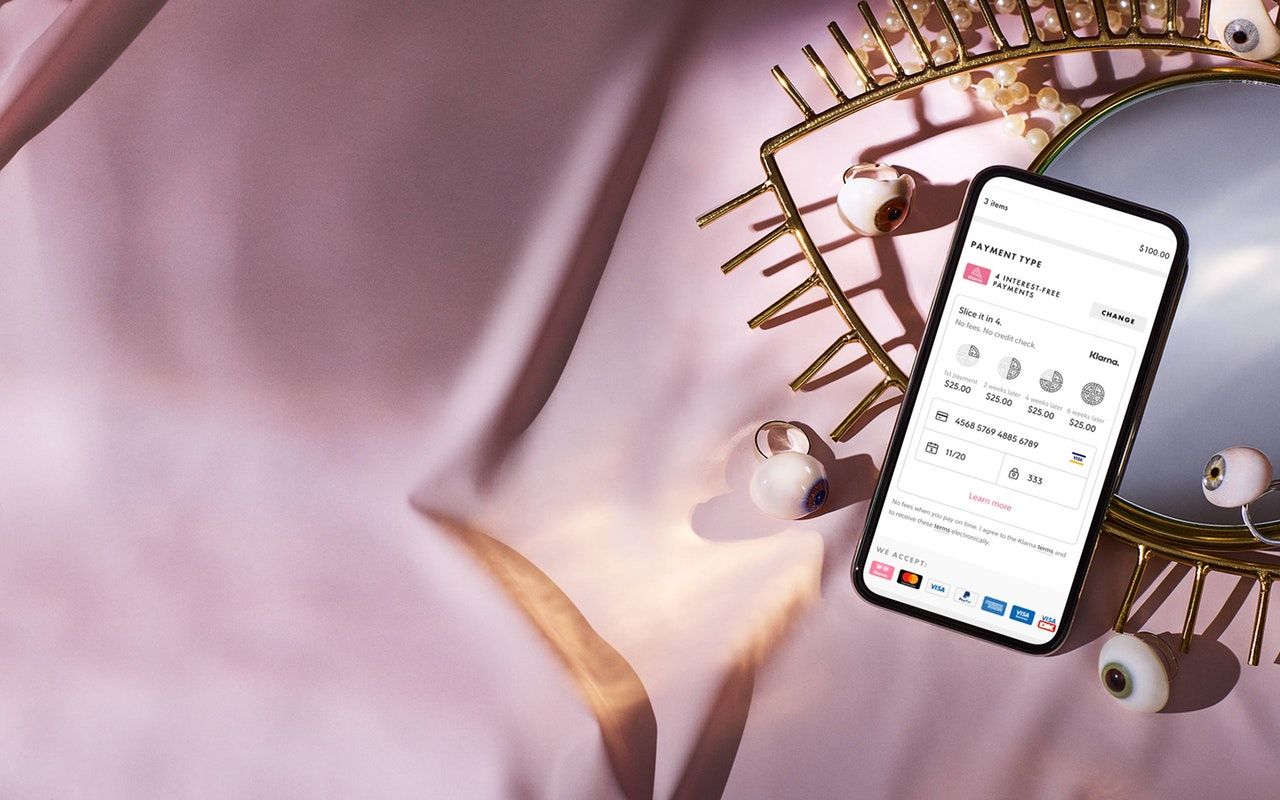

As the fresh new face of financial capitalism, Swedish bank Klarna and its ‘buy now, pay later’ service has dominated the world of e-commerce in the last few years.

Chances are, you’ve spotted Klarna at the checkout of one of the more than 4,500 UK retailers it is currently in partnership with. Or perhaps you’ve found yourself drawn to one of the inescapable advertisements currently decorating social media feeds and (pre lockdown) public transport systems, replete with taglines like: “When I’ve decided, Missguided”, “I’ll pay in three, JD” or “No drama, just Klarna”.

Leading the charge amongst its competitors in the growing FinTech (financial technologies) sector – Clearpay, Laybuy and Affirm being just a few others – Klarna is now valued at over £4bn and last month boasted of hitting seven million UK customers, with 88,000 new users opting for the company’s ‘buy now, pay later’ (BNPL) service every week in the second half of 2019, and 1.6 million people having downloaded the company’s app since it was launched less than a year ago.

Globally, Klarna’s rise is even more impressive; now available in 17 international territories, it’s clocked up 85m users and 11m app downloads. On average, Klarna now processes around a million transactions every day.

Introducing “No drama, just Klarna” 😍🙌 @Klarna’s newest UK campaign🇬🇧celebrating leading retailers and some major Klarna milestones. Fact: 50,000 new customers a week are choosing to ‘Pay later’ at retailer checkouts 🤩✨https://t.co/llW9pgiwWV pic.twitter.com/D484QhF7tE

— Klarna (@Klarna) September 24, 2019

Cloaked in twee pastel pink branding and counting stores like Topshop, Missguided, ASOS, H&M and Boohoo amongst its extensive list of partnered retailers, it’s unsurprising that Klarna’s success has come largely off the back of targeting millennials and Generation Z. Its biggest appeal being that its two most popular payment plans – spreading a purchase over three monthly instalments or the ‘try before you buy’ option, allowing you to pay up to 30 days later – promise no interest, no fees and only a ‘soft’ credit check that, so long as you don’t miss a payment, will not affect your credit score.

True as that may be, it’s not hard to see how this can still very easily spiral into something far more habitual and problematic. Interest-bearing or not, promoting and normalising a habit of spending beyond your means is still deeply irresponsible and only increases the likelihood of financial problems down the line.

The debt management organisation PayPlan recently conducted a survey of over 1,000 of their clients aged 18-34 and the results showed that the use of BNPL schemes had “contributed to a debt problem” for 73 percent of those asked. They warn of a significant increase in the number of young people coming to them for help after using services like Klarna, and plead that both regulators and the providers themselves, “step up now to ensure this type of lending doesn’t cause financial harm to future generations”.

Debt.

It is deeply alarming that BNPL services are contributing to more and more young people experiencing problems with debt, but it is also by no means an accident. Such schemes have emerged as part of a wider effort on the part of financial capitalists to lure the latest generation of young adults into the perpetual debt and repayment that is characteristic of life under neoliberalism.

They have emerged as a distinct, historically-specific response to both the economic conditions that young people face today, as well as the social and cultural milieu that defines ‘the Instagram age’ and all its tendencies towards hyper-individualism, and an insatiable drive for consumption.

Debt has been intimately bound up with the neoliberal project since it was first institutionalised at the level of the state by its transatlantic political torchbearers, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. It was during that transition away from Keynesian social democracy in the second half of the last century that Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi notes the principal role of the nation state shifted from being the “guarantor of social welfare” to the “enforcer of financial governance, the promoter of the systematic subjection of social activity to the repayment of infinite debt”.

It was largely through the right-to-buy programme, offering working-class people a discounted price on their council homes – so they could have their own little “piece of capitalism”, as David Graeber puts it – that Thatcher was able to sell her sweeping economic reforms to the public in the first place.

Of course, what Michael Heseltine, the secretary of state responsible for implementing the programme, called the single greatest legislative transfer “of capital wealth from the state to the people”, manifested less in any meaningful material stake in the economy than in an interest-bearing debt obligation that would take most people decades to pay off before they could truly call anything their own.

You were a homeowner on paper, but only insofar as you kept up with your repayments and lived within the necessary means to do so. The only real winners when it came to right-to-buy being the increasingly intertwined state and financial sector. The former was able to sell off a sizeable chunk of its housing stock as part of a broader, ideological assault on the welfare system and for the latter, which was to be massively expanded and deregulated, the proliferation of mortgages meant housing would become a formidably lucrative game.

Later, tuition fees would also emerge as another highly successful way of signing vast portions of the public up to a life overshadowed by debt. Bound up with the marketisation of higher education and the myth of a dog-eat-dog meritocracy, we were constantly told that the only way to get ahead of everyone else and land our dream jobs was through acquiring a degree. First introduced by new Labour in 1998, then notoriously tripled by the 2010 Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, tuition fees now mean getting yourself in debt to the tune of at least £27,750 for a standard three-year Bachelor’s degree. That’s before the addition of maintenance loans and interest, too.

Writing on student borrowing in his book Governing By Debt, the Italian philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato asks:

“What better preparation for the logic of capital and its rules of profitability, productivity and guilt than to go into debt? Isn’t education through debt, engraving in bodies and minds the logic of creditors, the ideal initiation to the rites of capital?”

For many past, present and future students, “education through debt” does indeed still act as a first real induction to the perpetual debt that Lazzarato sees as central to the neoliberal condition. However, the rise of the BNPL economy is an attempt to usher in a whole new form of initiation, out of necessity more than anything else.

Selling debt to Gen Z.

When it comes to younger millennials and Gen Zers, creditors have found themselves with no choice but to find creative new ways to coerce the latest crop of young adults into debt. After all, for those of us who came of age against the backdrop of the 2008 financial crisis, austerity and widening economic inequality, those lofty dreams of a ‘house to call your own’ or the ‘dream job’ simply no longer hold the same allure. Not because people no longer want those things, but because they now seem incredibly out of reach for so many.

A decade of wage stagnation following the crash paired with an ever-rising cost of living means that the prospect of saving enough money to lay down a deposit on a mortgage now seems laughable, especially for those without high-paying jobs or the support of wealthy family members.

As for higher education, many are also waking up to the fact that what actually awaits after you graduate is merely an abundance of unpaid internships for those that can afford it, followed by years of work that’s often low-paid, demeaning and precarious. The degree counting for nothing as you’re told to slowly ‘work your way up’ from the very bottom, one coffee run at a time.

In his 2009 book Credit and Community, the social historian Sean O’Connell looks at the forms of debt that have developed in working-class communities since 1880. When conducting interviews as part of his research, he frequently found that, despite the fact they very much were in debt, people only actually thought of themselves as being in debt when they were unable to make payments and had fallen into arrears.

It is precisely this logic that the likes of Klarna so successfully tap into. By positioning themselves as a new, more progressive type of creditor – with what appears, at face-value, to be an absence of any real financial repercussions – BNPL services make sure many young people fail to even see them as a form of debt in the first place.

In seeking new ways to repackage debt and sell it to a new generation who are now not only disenfranchised from, but also increasingly disinterested in, the traditional debt traps of home-ownership and higher education, BNPL has emerged as the latest financial instrument to make the accumulation of debt feel not just normal, but desirable.

Deliberately marketed at a generation who have seen a downward trend in the real value of their wages but who, at the same time, have only ever known the age of fast-consumption and social media, it’s no wonder that Klarna and their ilk have been so successful.

Jack Palfrey is a London-based writer, and a researcher on debt and populism.