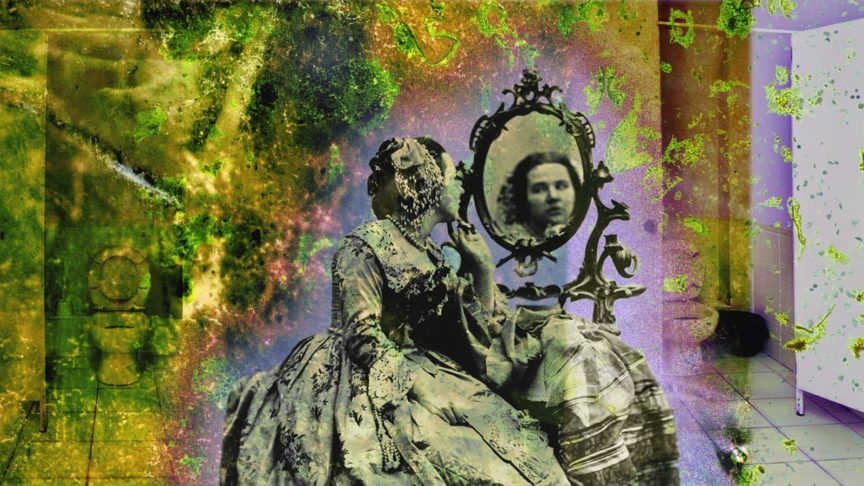

Filth: Trans Bathroom Panics May Be New, but Public Toilets Have Always Been a Political Battleground

by Eleanor Penny

8 April 2020

Amid yet another manufactured scandal surrounding the LGBTQ+ children’s charity Mermaids, a women’s minister has announced that “transgender women who have male bodies” should be banned from women’s bathrooms and changing rooms.

She joins republican senators and the trans-exclusionary ‘feminists’ of Mumsnet in pinpointing public bathrooms as the frontier of female dignity, to be defended against the suspect ambitions of gender-traitors and their allies everywhere. However far we slip into the pits of disaster, armies of queer-botherers persevere in their quest to protect society against the vicious scourge of people using bathrooms.

At first glance, trans bathroom panics seem trivial – a bad-faith media circus, a creepy fixation on where total strangers empty their body’s waste products. But public bathrooms have long been a political battleground. This is just the latest salvo in an ongoing battle over whose bodies are worthy of dignity, whose lives should be protected, whose existence the arbiters of public morality can bring themselves to tolerate.

Public bathrooms are to town planning what a decent soldering iron is to aeronautics – without it, everything falls apart. Dial back a few hundred years and the streets of the leafy enlightened cities of Europe were quite literally flowing with shit.

As industrialisation cranked into gear, more people crammed themselves into urban centres to find work, overwhelming previous hygiene institutions such as ‘chucking a bucket of piss out the window at a designated time’. Diseases of human proximity ran rampant, with cholera and tuberculosis carrying off countless thousands every year. Clearly, a solution was needed for mobile populations, and unzipping in the street wasn’t a long term solution here.

Victorian efforts in ‘public hygiene’ pioneered building bathrooms – to curb a health crisis, and lay down the infrastructure for a modern industrial hub not so mired in the economic importunity of filth and disease.

Then as now, urban design was not a neutral calculation of waste flows and bearing-weights; it was also a public reckoning with who and what the city was for. The new ethic of ‘hygiene’ had a slippery interchange between the biological and the bigoted, which greased the wheels of social exclusion. ‘Cleanliness’ was equated with respectability, and the middle classes saw the urban working classes’ sparse access to washing facilities as confirmation of their moral laxity. Indeed, sex workers were hounded from public places as apparent carriers of disease.

Public bathrooms were originally intended only for men. Though necessary, they were still seen as spaces of indecency and threat – not the place for the delicate, fainting sensibilities of the ideal-type woman. The ‘urinary leash’ tied women to their homes, stretching only as far as the houses of friends and relations. This was precisely the point; clipping the wings of the so-called ‘angel of the house’ so she couldn’t fly too far from her designated roost of kitchen and hearth.

Bathrooms meant health, mobility, security. If you couldn’t reliably access a bathroom, your options shrunk – about where you could travel and socialise, where you could work, if you could work.

Many opponents of trans bathroom access will evince a notional support for trans existence – just that they don’t want them in public bathrooms. Anyone can recognise the cadences of your garden-variety homophobe: “I care mind what you perverts do behind closed doors, just don’t do it in front of me”. The problem is when people cross from the margins into the centre, when they leave the private realm and claim their right to the public. It can under no circumstances be tolerated.

Of course, working class women have always had to stray beyond the reach of their urinary leashes – for paid work, for domestic chores, for socialising. Those who did would often have to lift their skirts to piss in the street, through a slit in their underwear specially designed for this purpose. A dirty, dangerous business for which you could face being shamed or set upon. Our class, respectability, dignity is marked by our relationship to dirt – our own, other people’s.

In Purity and Danger, anthropologist Mary Douglas wrote that dirt is “matter out of place”. People out of place are marked as dirt, as disposable. Those excluded from the public realm have no right to enjoy its protections. Trans women are murdered at “epidemic” rates. In 42 states of the US, their murderers can claim a ‘trans panic’ defence; as soon as the victim was revealed to be trans, they lost the right to protection under the law.

Women gained access to public bathrooms only after long pressure campaigns, bolstered by the influx of more women into formal workplaces, particularly in the industrial cities of the northern United States. As women claimed their rights to public space, the urinary leash was strained to snapping point.

For queer men, public bathrooms have long been an important space of sanctuary. The police quickly cottoned on – and undercover stings became common. Spry and handsome bobbies were dangled as bait for men they wanted to snag on charges of public indecency. When intimate moments are invaded by the prurient and unforgiving spectacle of state-mandated violence and shame, everyone becomes a suspect and everyone becomes a cop.

Public bathrooms are temples of ritual vulnerability. Whether we want to or not, we hear, smell, spectate strangers weeping openly, shooting up, emptying their bowels, having sex with other strangers. We encounter the messy reality of other people’s bodies, wrenched into accidental intimacy, sideways collectivity. When trans people are excluded from public bathrooms, it is yet another way of marking transness as other, as not part of the collective experience of being us.

And as Laverne Cox explained: “When trans people can’t access public bathrooms we can’t go to school effectively, go to work effectively, access health-care facilities — it’s about us existing in public space”. It means being stripped of basic infrastructure, excluded from public transport, further justified as targets for vigilante enforcers of what passes, in a vicious imagination, for justice.

Bathroom bills are reliably justified on the grounds of ‘protecting women’ from the spectre of male violence; that gender-neutral or trans-inclusive toilets would prove a prime opportunity for undercover predators to jump women in vulnerable moments. Overlapping paranoias compete for press oxygen; that men would spuriously pretend to be trans women for a day (and who amongst these self-ID snowflakes could tell them otherwise?), that trans women are secret predators getting off on the perverse pageantry of infiltrating the feminine sanctum.

It seems to matter little that all this has been repeatedly debunked as statistical nonsense or swivel-eyed conspiracism. They aren’t really propositions to be proved true or false – they are ways of telegraphing disgust. Of signalling to those who fall outside normative conceptions of gender: ‘you don’t belong here’. This may be where we empty our bladders – but the real filth is you.

There are zero confirmed cases of a man pretending to be a trans woman to commit sexual assault. It’s a fever dream of conservative culture war strategists and overly-online obsessives determined to forge a cover story for their own reheated prejudice. There are, however, many cases of cis men assaulting people in women’s bathrooms without such a pretence. As journalist Paris Lees has charted, there are many cases of gender-non-conforming cis women being stopped in public bathrooms on suspicion of existing-while-trans.

If we try and actually enforce bathroom bills, we end up with a patchy surveillance system that targets people for looking insufficiently womanly, a mandate to poke around in our underwear to see if our bodies are socially sanctioned. If we don’t, it becomes a blank cheque for a civilian police force volunteering to enforce gender norms invented by the state. Everyone becomes a suspect and everyone becomes a cop.

It has no hope of preventing men from committing assault – a misdiagnosis with no hope of cure. Instead, bathroom bills offer a biological separatist logic according to which people with ‘male bodies’ are incorrigible brutes, and our only hope for salvation is to keep them briefly at bay – in this one extremely specific context. Convenient, in so far as it exerts no pressure for change either on victim support systems or on men.

That non-binary people often struggle even with trans-inclusive binary bathrooms is sometimes taken as proof that non-binary existence is a frivolous pretension which buckles easily before the immovable biological facts that ladies pee over there and men pee over here. People are forced to justify themselves before arbitrary infrastructure – rather than the other way around.

It refuels an age-old engine of making gender: intimate state surveillance, on the grounds that any deviation from a narrow norm is a threat to the integrity of public life. The policeman’s truncheon governs where we can and cannot go, the clinician’s scalpel pries back the skin to rummage around in our organs. No aspect of our lives is left unexamined by the guardians of a shrinking vision of what correct womanhood looks like. Are our genitals arranged correctly? Are we moving through the assigned spaces with the assigned supervision? Are we behaving as a lady should?

How we arrange our dirt, where we pee, where we shit, who we shit next to – all of it is recruited in the effort to re-invent gender’s claim to being a series of natural sexual categories, twin biological fates kept in check by the flimsy comforts of the bathroom walls, and the frothing neuroses of their defenders. In some circles, I believe this is mistaken for feminism.

Eleanor Penny is a writer and a regular contributor to Novara Media.

This article is the first instalment in a new series on the political economy of things we consider to be waste, rubbish, junk – or filth.