An Unprecedented Economic Crisis Is About to Hit the Global South. We Must Cancel Debts Now

by Grace Blakeley

9 April 2020

The global South is facing an economic crisis on an unprecedented scale. More capital has left emerging markets in the last 90 days than in any previous year on record, as investors who have spent the last several years sinking money into emerging markets suddenly flee in favour of the safe haven of the United States.

As increased borrowing becomes the only option for many poorer countries, and the cost of borrowing rises, it is crucial that figures from across the political spectrum unite behind demands that wealthy states write off debt. A failure to do so would spell catastrophe for the global economy.

Animal spirits and herd behaviour.

The problem is a familiar one. Investors’ decisions, whether in a boom or a bust, are driven as much by ‘animal spirits’ – optimism and pessimism, influenced by herd behaviour – as they are by any assessment of the objective value of the asset they are buying. When they are optimistic, they will channel money into risky but profitable ventures all over the world – often borrowing large sums of money to do so. But when the tide turns, they are likely to flee risky investments, either hoarding cash or sinking money into very safe assets like US government debt.

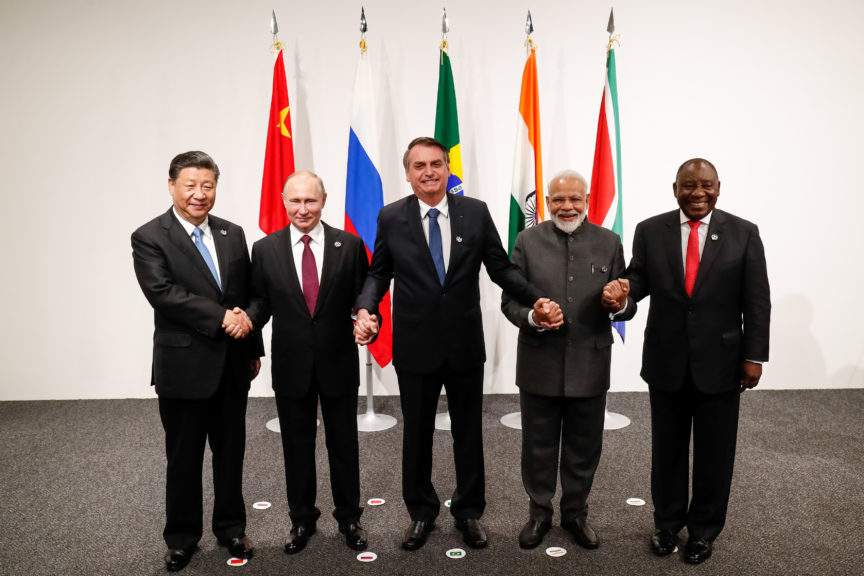

The post-crisis excitement about the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) – and latterly, the MINTs (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey) – saw huge sums of money flow into the global South. Many of these countries had been less severely affected by the financial crisis than those in the global North and were also benefitting from China’s huge post-crisis stimulus package.

Low interest rates in the global North also sent investors reaching for yield – seeking out investment opportunities that would provide them with higher returns.

Sometimes this capital sought out genuinely useful infrastructure projects; sometimes it was lent to foreign governments; and sometimes it was channelled into international real estate or used to speculate over commodity prices. In other words, some of this investment has undoubtedly helped the people of the global South, but much has not.

Now, at the very moment that workers all over the world are relying on states to increase their spending on public services and social security, investors are fleeing these formerly ‘emerging’ markets, concerned about economic impact of coronavirus.

Many states in the global South could see their healthcare and limited social security systems overwhelmed by the virus – either states will respond, meaning more borrowing from foreign creditors, or they will not, meaning output will take a substantial hit.

Lender of last resort.

As investors sell government bonds, the cost of government borrowing will rise, making it harder for states in the global South to pay their debts in order to support their ailing healthcare systems and struggling unemployed workers.

Exchange rates will tumble, making it far more expensive to import necessities from abroad – but without offering the solace of rising export demand given the massive contraction in global trade currently underway.

At this point, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) will step in and play the role of lender of last resort, providing ailing economies with emergency funds to repay their debts. These emergency loans often come with punitive conditionalities, like those imposed on global South countries through the structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) of the 1980s that followed the global South debt crisis of the 1970s.

This crisis was used as an opportunity to ‘open up’ poorer countries to international investment – a euphemism for preventing democratically-elected governments from embarking upon state-led development programmes in favour of removing restrictions on capital mobility, selling off public assets and cutting public spending.

These SAPs often negatively impacted human and economic development – especially in sub-Saharan Africa. The much-touted effects on economic growth turned out to be negligible, while the poorest were hit hardest by cuts to infrastructure, education and public services.

Over the long term, the debt crisis and the SAPs curtailed incomes, and therefore demand and economic growth. As a result, the size of these nations’ debts only increased relative to their GDP.

A global debt jubilee.

Eventually, realising that some of the poorest states in the world were suffering under a burden of completely unpayable debts, pressure mounted for a global debt jubilee. Remarkably, this was partially achieved in 2000, when the Jubilee Debt Coalition – a network of charities and religious organisations – successfully pressured the UK government to write off a substantial portion of the debts owed to it by global South states. Several other countries followed suit.

It was not long before these debts began to accrue once again. The global South has been continuously promised that, if it only sticks to the prescriptions delivered by institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, it will ‘catch up’ with the global North.

In fact, ongoing neocolonial and imperialistic relationships between the global North and South – not to mention the huge amount of money that escapes the world’s poorest states through money laundering and tax avoidance – have prevented most of the world’s poorest states from doing so. Those that have – most notably, China – have ignored all of the advice of the international financial institutions and focused on state-led development.

International solidarity.

Today, after another decade of investment in the global South, promises of development remain unfulfilled. Now, as a global pandemic generates economic turmoil, another debt crisis threatens to hit those states that are least able to withstand it.

Again, governments will be unable to meet their liabilities to both their people and international creditors. Again, the international financial institutions are likely to provide emergency loans that protect creditors at the expense of the people. And again, the debt will simply carry on piling up when the crisis is over.

On Tuesday, several organisations involved in the original call for a debt jubilee signed a letter calling on wealthy states to organise another debt write off for the global South. It is critical that figures from across the political spectrum now unite behind these demands, not least the new leader or the UK Labour party – a man who has made his political career based on campaigns to promote international cooperation and solidarity.

If Keir Starmer fails to join the calls for a debt jubilee for the global South, it will become extremely clear that the only kind of international solidarity he ever cared about was that which exists amongst colonisers, against the formerly colonised.

A failure to write off debts can only spell catastrophe for the world’s poorest countries and, by extension, the global economy.

Grace Blakeley is an economics commentator and author of Stolen: How to save the world from financialisation.