The Burner Episode #217: a Tech Exit to Covid-19?

James Butler asks: what would a tech-led exit from lockdown look like? And James Meadway tells us what we should make of the OBR’s ‘bouncing ball’ scenario on the economic shock.

- Published 15 April 2020

- Subscribe to Podcast

Transcript

Good morning. This is The Burner. I am James Butler and it is Wednesday April 15 and we are still in lockdown.

The question on everyone’s mind is when we will be able to exit the lockdown. Well, not anytime soon. It looks – and the announcement will come tomorrow – like we’re in for a serious extension. There’s some warning intermittent lockdowns and social distancing will become the norm until a vaccine is found.

Those of you who’ve listened to this show for some time will know that I think there is a trilemma, a three-way pull at the heart of coronavirus policy. The three sides of that triangle are the economy, public health and civil liberties. In the classic trilemma formulation, you can satisfy two sides of the triangle but never the third. You might put everyone back to work, you might allow them to circulate freely however they want, and that might mean you get what you need on the economy and certainly everyone’s free, but the public health implications would be catastrophic.

This trilemma is not a perfect heuristic for these problems by any means; issues can be lopsided. The differences between them can be actually hard to delineate. Do we have a right to health, for instance, or at least not to be recklessly endangered by our, by the actions of our government or by businesses? And where does one issue end and the other begin? It’s useful in thinking through political problems as we encounter them.

One of the solutions that has been intermittently floated by the government has been a “medical passport”, something that certifies that you have had the illness and are therefore free to move around and, importantly, get back to work. The latter of these perhaps of more importance to the government than the former.

Now, such a passport is a long way off. It would depend on the existence of a reliable and widely available test that would demonstrate that you have had the illness. Although the government made headlines a couple of weeks ago by saying they were definitely going to have just such a test soon and it had indeed purchased them on the millions. In fact, they turned out to be too unreliable to use.

Let’s imagine that we do have just such a passport and actually there are civil liberties issues involved. All sorts of uncomfortable issues from that picture, about segmenting the population according to their physical health or perhaps their perceived level of risk, in turn, spring two problems.

One is [a problem of] simple compliance to blanket measures [with these gaining] some popular buy-in as they affect everyone equally. Would that remain the same or would there be a tipping point of some kind where people who are low risk of death themselves just start to flout the restriction? But there’s another question about this kind of policy, it comes from the way that political decisions which are made on the hoof often stick around.

We’ve talked about this a lot before, especially in our whistle stop of various European emergency powers: a power arrives in one emergency or a new law is passed and then it just sticks around in one form or another and [then] there’s a kind of new normal. But, in this case, I’m thinking about something a little different.

[It’s] not that the measures themselves might stick around, but the way of approaching them will set the new standard for government interventions of this kind. If you think this is just a once in a century event at most; that a viral pathogen just happened to mutate to just exactly the rate of infection and lethality needed for mass spread, then perhaps this doesn’t matter. But there’s another argument that says the incidents of pathogens like this are likely only to increase with, among other factors, human intrusion on nature.

What’s important here is twofold. Which political answers become acceptable in a time like this? [Do] they set the pattern for dealing with another pandemic? And how they then feed back into the wider matrix of policymaking and politics? What might be a greater acceptance of that kind of population segmentation? [On the other hand, will there] be a greater disdain for the old, along the lines that some of the hard right are now arguing? That, effectively, “your nan must die so JP Morgan’s profit rate can tick back up, sorry”?

Obviously both of these are capable of some terribly dark inflections, but I also must resist the pool to dystopia, which becomes so easy in times like these. There are other inflections and other shifts of value, which might well come out of the other side of this, but which are hard to see as yet. Perhaps more on dystopia in the coming week.

But if not medical passports, why not an app? It’s been a few years since the fall back idea of every politician in a bind was an app. Indeed, since Matt Hancock, now the health secretary, launched Matt Hancock the app (called Matt Hancock MP) – a true low point in digital innovation. But, obviously, [this trend] has been making a comeback since the importance of contact-tracing has been recognized. The same Matt Hancock did indeed float a UK app for contact-tracing, usually using mobile phone location data. Such an app would be voluntary, it is at least suggested. One can see it becoming very heavily suggested alongside a medical passport for instance.

And, yes, there are all the civil liberty concerns. However effective the “Chinese wall” or arms think secrecy puts in place, I really don’t like giving the government access to my location data, or easier access anyway, given that a few years ago the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) was revealed to be widely spying on British citizens to a rather muted response.

Maybe we’ve all become simply inured to the idea of an all-seeing eye staring at us from Cheltenham. [Although] we’re certainly all too blasé about our personal data, privacy rights are tremendously difficult to re-establish after they’re gone. But let’s put the explicitly political concerns about bio surveillance to one side and let’s not forget about it.

Would such an app even work? We know that contact tracing actually matters and can be incredibly effective, but most of the forms proposed for use on phones have their limits. Technology – say a piece of software that logs an ID for each phone it comes near using Bluetooth – has its limitations. Let’s say I have a conversation with my neighbour on the boat next to me, standing in a couple of meters apart while the wind blows; my phone might log that as a contact, but the risk of infection would be extremely slight. [Now] imagine we’re in a supermarket queue, all behaving properly and properly socially distancing, [the phone] would that flag as a contact.

There are a host of other problems as well, all normal to the questions of human behaviour around technology. If I start to get loads of notifications on my phone that I’ve been near someone who’s tested positive, does my behaviour change? Do I just start clicking “yes”, go away on all the notifications, kind of half consciously just wanting to get rid of them? That’s not to mention the whole host of normal problems from bad actors. Let’s say my kid wants [to miss a day of] school because he has a test coming up that he hasn’t prepared for time, to ping some positives on the app. That’s just the sunniest kind of bad actor. There are far, far worse. These questions are raised by Ross Anderson, professor of security engineering at Cambridge in a blog post, where he looks over some of the immediate problems that a contact-tracing app might just present to us.

Now, the most important things to take away on a purely technological front is that as much as politicians might wish otherwise, there’s no magic bullet here. There’s no pristine map of data, which also understands the complexity of human interaction, just sitting out there waiting to be used by government to solve the problem. In turn, there’s no entity which doesn’t suffer mission creep when it gets his hands on this kind of data and. In turn, for the data to be useful, there’ll be pressures against its full anonymisation. Raw data, as they say, is an oxymoron. None of that is to say it won’t both be likely to exist and a useful tool, but the more technologically literate press might actually ask some of these questions of a minister when he promises a magic text solution coming down the line. [The press] might ask for instance, what happens to the data in the long run? Don’t hold your breath. Still, work on an app or a protocol to handle data is happening at breakneck speed with suggestions about encrypted and distributed pseudonymous logs and the like.

I just wanted to point out some of the five questions that have been raised by the ACLU, the American Civil Liberties Union, which I think are good ones to ask. Especially on health data, but perhaps about every app that harvests data and especially those shared with government organisations.

One, what is the goal of the deployment? Two, what data? For instance, is it aggregated and anonymized and how precisely can the information pinpoint locations? Three, who gets the data? Is it the government that gets access to the raw data? Is it shared only with government entities targeted to public health? Does it go to academics or to hospitals? Does it remain in the hands of the private entity, which initially collected it? Four, how is the data used? In terms of actual government action issuing or enforcing quarantine orders, is it used more sharply or more punitively by the disciplinary arm of the state? Five, and most importantly in some ways, what is the lifecycle of the data? A question which circulates around all of these scandals around data is just that: when would it be deleted? With the police of course being notorious for failing to delete data. Worth keeping those questions in mind, especially as the general level of technical literacy among our political lords and masters seems to extend to taking a screenshot by pointing a camera at a monitor.

[Lyrics of Abba’s Money, Money, Money]

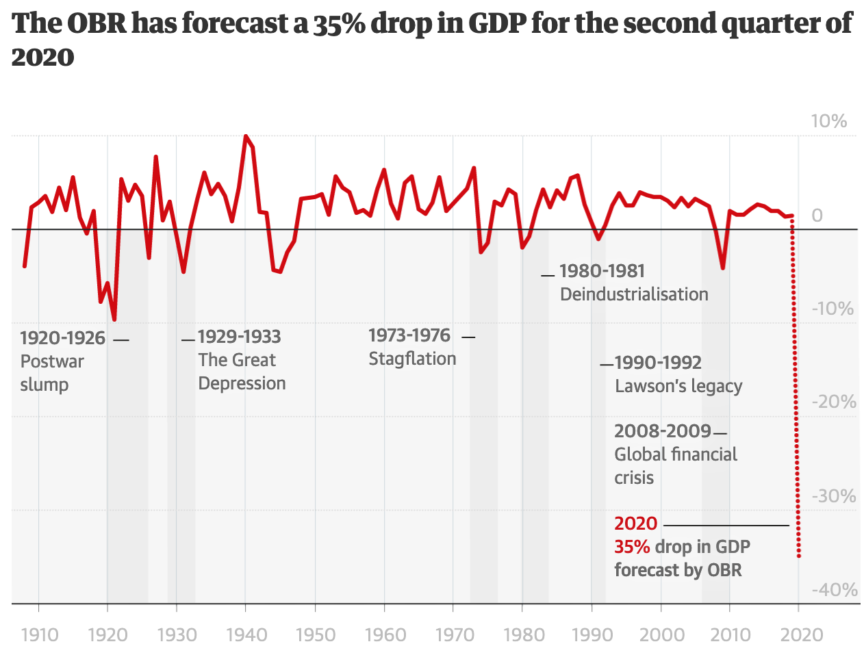

You will doubtless have seen yesterday the Office of Budgetary Responsibilities’ (OBR) scenario modelling circulating for tracking GDP in response to the lockdown.

It’s a scenario that’s basically a line that crashes massively this year, then rebounds and sores to the sky in the next year then everything returns to the projection. The IMF has produced similar modelling – because I guess you have to call it that – for the global situation. They also warn at the same time, this is a global recession, possibly equivalent to 2008, or really looking much further back the great depression, indeed, perhaps the worst since the South Sea Bubble of 1720 [the speculation mania that ruined many British investors]. Some are calling it “the great lockdown”.

I asked James Meadway what we should actually make of all this.

James Meadway, economist and former advisor to John McDonnell

JM: The government’s official forecasts, [which is] the OBR, today produced its first assessment of the economic impact of Covid-19 as would be expected. The crisis is overwhelming. [It shows] a 35% drop in output in the three months to June this year and unemployment rising to something like 10%. But don’t worry too much about this since, if the OBR projections are to be believed, the economy will grow at an extraordinarily rapid pace from June onwards. Like a rubber ball dropped from a great height, the economy will hit the bottom in mid-summer and rebound to new and greater heights before settling back down exactly where it was before.

Now, in fairness to the OBR they do say in the report that the projection for an extraordinarily rapid rebound is based on the assumption that the British economy will in fact rebound. It’s not, in other words, a forecast so much as a scenario – a description of one possible path for the future to take, not a prediction of the past it will take. It is based on the assumptions that the fed into the model, it is not modelling of what will happen. But, importantly, this is the best-case scenario. Any other remotely plausible state of the world is going to look a lot worse than this.

The IMF for its part also produced its forecast today and presented a significantly less rosy picture, with the UK among the worst affected of major economies well into next year. But beyond the immediate crisis, there is every reason to think that Britain will not be looking at the so-called “V-shape recovery” the OBR described – so rapidly down and then rapidly back up again. It’s something more like a U or even an L shape to the future. In other words, a period of slump followed by a long slow recovery, a U on the graph, or simply no meaningful recovery at all, making the shape of an L.

The reasons to suspect that we will get a U or even an L shape are in two parts. First, that even the exceptional support offered by this government to those facing unemployment or businesses facing ruin won’t be enough. We’re too many people, the self-employed and small businesses especially falling through the cracks. The cracks are there in the supporting parts because, in typical treasury style, the assistance offered has been designed to be unwound as quickly as possible. For instance, it would have been quicker, easier and fairer to simply make universal payments to everyone. But making something universal makes popular. To think about the NHS, everyone gets it, everyone loves it and so it makes it harder to get rid of later when you want to unwind all the support that has been offered. [However,] the more people are unemployed and pushed towards destitution, the more businesses go bankrupt and the more protracted and uncertain the recovery will be as a result. If fewer people are able to spend and fewer businesses around to employ them, demand will be weak and if demand is weak the economy slows down.

The second part is more speculative, but early signs point towards it. After the 2008-2009 crash, now dwarfed by this economic cataclysm we are living through, economies like Britain never recovered back to where they were; growth was permanently lower, in Britain dramatically so and living standards permanently depressed. After this shock with supply lines torn up, new working habits adopted or imposed and, potentially, the high costs of sustained anti-pandemics surveillance or medical monitoring or data sharing, there is a substantial chance that growth in the other side of this crisis will be depressed over the longer term. This is the L shape.

We can speculate about the future, but the really important points are these. First, the government is already under pressure to end the lockdown and dramatic economic figures are being used to add weight to the argument that it should be ended quickly. We shouldn’t let them. Protecting people is more important than protecting GDP. Second, arguments for a return to normality including a return to austerity. We’re already being lined up and the OBR story of a rapid rebound plays into it. We should be clear on this too. We do not want and should not accept a return to the status quo after this has played out. The postcode economy must be more resilient to shocks, more secure for more people and certainly far fairer than the pre-Covid shambles we’ve been living in.

JB: My thanks to James for that. That’s precisely the point I think that is important about resisting calls both to sacrifice people, human beings, on the altar of GDP and then [resist the] likely push towards austerity which might come down the line and is indeed already being invoked. The politics of this economic shock are coming, and they won’t be quietened by Rishi Sunak seeing his own praises at a lectern in Downing Street.

Headlines this morning

As a headline on a piece by the notoriously cheery Martin Wolf in the Financial Times puts it: “The global economic system is already collapsing”. So, be prepared.

On my mind over the weekend and yesterday has been the UK death toll, which as of yesterday passed 12,000 in the official figures. It is a staggering number and it’s hard to visualise. When you really think about it, [it’s] hard to bear. The Office of National Statistics yesterday also highlighted, and I think this is important, that the actual deaths from Covid-19 could be 15% higher than the daily government figures suggest. [There were] strong indications yesterday that the number of deaths in care homes is being wildly understated.

On top of this, graphs produced by the government comparing the international situation don’t seem to compare like for like numbers. The French numbers, which seems to be above ours on the government graph, include deaths that the UK’s numbers currently do not. It is obviously not good enough, but the government seems pretty diffident when it comes to actually doing anything about it. That’s at least on the basis of their briefing yesterday.

There were claims last week, and plausible ones, that forecasting this stuff genuinely is truly difficult. The UK is death toll may end up higher and higher per capita than any other nation in Western Europe. That is undoubtedly a political question and a question which bears political responsibility. It raises questions about who did what and when, when [did they start] to take it seriously and [other questions] about failures of reaction and preparedness.

We have news today that the ventilators – rolled [out of] manufacturing lines after the health secretary’s appeal – won’t match up to the specifications needed for Covid-19 patients. That [political] question, again, should be staring us right in the face. But, instead, it’s those [death toll] numbers that stare at us right in the face. Those numbers displaced from the front pages again and again as they ratcheted up last week – as the press worked itself into a permanent lover over the fate of just one man – with none of the seriousness and gravity and dire prognostications they gave about Italy when it was hitting the same numbers a few weeks ago.

Twelve thousand deaths. That’s the thing that should occupy us, each of them. We should resist the frankly horrifying push to treat these as deaths that would have happened anyway sooner or later [like] it’s nothing to be concerned about and “let’s get the economy rolling again”. We must not become numb to them and we must not treat them as inevitable casualties; sad, perhaps, in some abstract way, but of little concern to politics.

The best way I know to keep that in mind is this.

“No people are uninteresting.

Their fate is like the chronicle of planets.

Nothing in them in not particular,

and planet is dissimilar from planet.

And if a man lived in obscurity

making his friends in that obscurity

obscurity is not uninteresting.

To each his world is private

and in that world one excellent minute.

And in that world one tragic minute

These are private.

In any man who dies there dies with him

his first snow and kiss and fight

it goes with him.

There are left books and bridges

and painted canvas and machinery

Whose fate is to survive.

But what has gone is also not nothing:

by the rule of the game something has gone.

Not people die but worlds die in them.

Whom we knew as faulty, the earth’s creatures

Of whom, essentially, what did we know?

Brother of a brother? Friend of friends?

Lover of lover?

We who knew our fathers

in everything, in nothing.

They perish. They cannot be brought back.

The secret worlds are not regenerated.

And every time again and again

I make my lament against destruction.”

― Yevgeny Yevtushenko

That’s a poem by Yevgeny Yevtushenko and I think there are worse guides for thinking about an ethical response and the grounding of a political response to all of this.

In the news today, [there was] effectively a wide-out briefing that the lockdown is definitely still going to continue for some time. That announcement will come tomorrow, but it appears effectively decided.

Donald Trump, in his latest exercise in sociopathy, announced that he was pulling all us funding from the World Health Organisation in the middle of a pandemic.

The Department for Work and Pensions is due to announce new details on the impact of those 1.4 million new universal credit claimants. Matt Hancock is due to talk about social care at this afternoon’s briefing.

Keir Starmer does his first proper big round of news interviews this morning, mostly on the coronavirus, but I wonder how far he’ll be pushed on that leaked Labour report, which Ash Sarkar of course talked about on The Burner yesterday. [This leaves] us with a question, and one which I find hard to answer in a purely political sense, in the sense of the politics of the Labour Party: What does Keir Starmer actually want? What should this report give him the opportunity to do? As ever, I find him like an Easter Island head: granite, silent, impenetrable – maybe slightly more nasal. More [on] that to come.

Last, this from Cardi B on a livestream with Bernie Sanders last night:

Cardi B: “They put capitalism, money and trading goods, before our health.”

You can say that again.

All right. As ever, send me tips, stories, angles, especially news from abroad and news from the global South on the coronavirus. What are we missing? You can hit me up on [email protected].

And please, do stay safe, stay home, wash your hands and don’t be a prick. That’s it. This is The Burner. I’ll see you tomorrow.