To Understand Why the NHS Is Struggling to Respond to Covid-19, We Must Look at Who Runs It

by Jo Sutton-Klein

21 April 2020

Some coronavirus policies are inherently quicker and easier to implement than others; after lockdown was announced, it took just three days for police to be given powers to enforce the new measures; it took two days for schools to close, and when the government finally announced pubs and cafes must not stay open either, it was just a matter of hours before they stopped serving customers.

Yet the NHS is still struggling to implement policies and meet targets that should be perfectly achievable, because of fundamental problems with the way in which it is run.

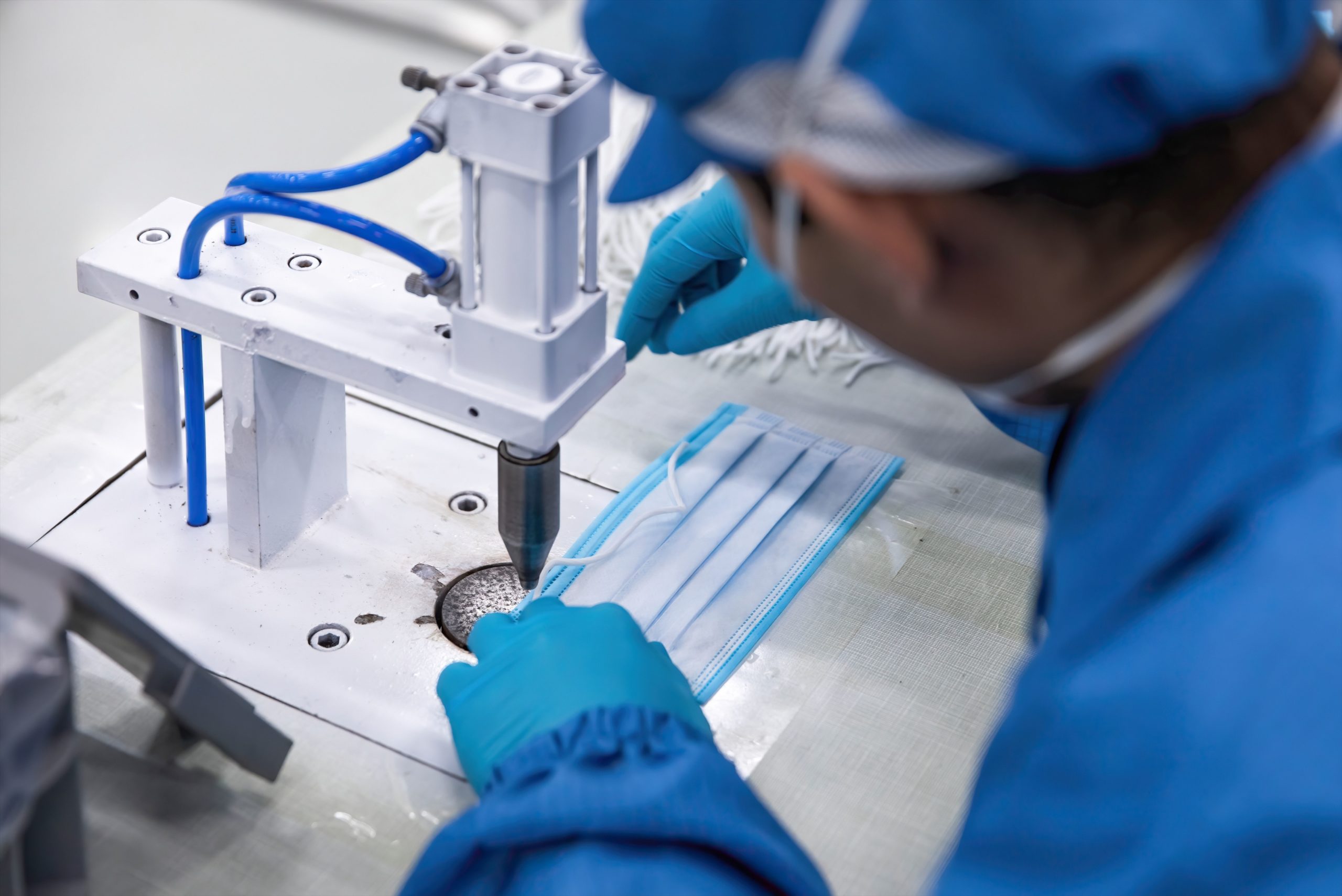

Despite an insistence from the government that there is enough personal protective equipment (PPE) to go round, NHS staff are not only being left without face masks, goggles and gowns, but they are being gagged by their managers when they try and speak out about the shortages.

At the same time, our health service looks set to miss its already reduced target of 100,000 Covid-19 tests a day by the end of April.

Implementing Covid-19 policies within the NHS was always going to be one of the biggest challenges in responding to the pandemic, and the government made this harder still by missing multiple opportunities to prepare our health service before the crisis really hit.

But there is another reason why even now, weeks on, the NHS is still struggling to put policies into practice; inertia in the NHS is not the fault of powerful yet incompetent individuals, but an indication that the very structures that underpin our health service are inadequate.

To understand the problem, we must look at how the NHS is run and why.

Who runs the NHS?

The NHS today is run by managers. But it hasn’t always been this way.

General managers were first introduced to the health service in 1983, following a damning report by businessman Roy Griffiths.

Griffiths was taken aback by the lack of management within the NHS. He was unapologetic in his assertions that the NHS could and should be run in a similar way to businesses, naming ‘quality of product’, ‘productivity’ and ‘cost improvement’ as values it should hold.

He even specified that the chief executive of what is now NHS England, should not come from an NHS or civil service background, rather they should be recruited from the world of business.

It is the ‘business-minded’ people recommended by Griffiths who run NHS England and NHS hospitals today.

It is tempting to lambast the presence of business people in the NHS – as a junior doctor, I personally find it unsettling that the NHS Chief Executive Simon Stevens, for instance, boasts that he spent a decade working at a commercial health insurance provider. However, this misses the point; it is not the people themselves causing the problems, but the structures they are part of.

The general management structure of the NHS has come to embody the values that Griffiths wanted. NHS management is constantly trying to improve the health service’s efficiency and value-for-money. It is this obsession with business metrics that left it ill-prepared to mount a response to Covid-19.

Health workers know what health workers need.

NHS managers don’t know what to do with a blank cheque and instructions to take whatever measures are necessary to save lives, because that is not what NHS management has ever been about.

The daily silver command meetings that are taking place in hospitals across the UK systematically exclude frontline hospital workers, to the extent that it is easier for NHS workers to communicate to their managers via the media than to navigate the steep hierarchies within hospitals, to reach the people in charge, who sit so many many echelons above them.

General managers are not just failing to hear the needs of frontline NHS workers, but they are also missing out on the suggestions and ideas that are obvious to those at the sharp end of this crisis.

The system is so dysfunctional that we’ve seen individual doctors and nurses bypass NHS management in coordinating the manufacture and distribution of visors and goggles from local schools and universities.

Non-clinicians do have a place in the running of the NHS, but it must be alongside frontline workers. Administrators, along with doctors and nurses, formed the core triad of the ‘consensus management’ system which was in place prior to 1983.

This multidisciplinary triad ran NHS hospitals and larger NHS structures such as regional health authorities on the basis of consensus. The consensus management model was judged to be broadly successful (though not perfect) in its time.

It’s easy to imagine how a management model which includes doctors, nurses and administrators as equals would have been better able to respond to Covid-19.

Democratise the NHS now.

This pandemic has not only highlighted the disempowerment of frontline staff in the running of the NHS, but also the exclusion of the wider public.

Since the very beginnings of the NHS, the wider public has been given some say in how it is run through representation on local health boards or equivalents, but nowadays this is nominal at best.

Since the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, public involvement in the NHS has been through a network of local organisations called Healthwatch. While Healthwatch does indeed advocate for public involvement in the NHS, this is as consumers rather than participants.

Healthwatch Sheffield proudly claims it is ‘your local consumer watchdog for health and social care services’ – it need not take an international pandemic to make it clear that health and healthcare cannot be ‘consumed’.

Looking at the exclusion of the community more broadly, the mutual aid groups that have been set up across the country are evidently a form of health service, but they have been unable to integrate into the NHS.

Meanwhile, communities have little influence over local Covid-19 policy, such as the shutting down of parks, reduction in public transport or actions of the police – despite having the clearest idea of their own needs and vulnerabilities.

It was always inevitable that the NHS would undergo another set of reforms before long, but Covid-19 has undoubtedly escalatd the timeline. When the next set of major reforms take place we should reject the premise that a general management structure is the only option.

But we do not need to wait until the dust settles to demand that frontline NHS workers and local communities are not just given a voice, but also given the power to influence and enact NHS policy – we can and should demand that now.

Jo Sutton-Klein is a junior doctor in Sheffield and has an MSc in social epidemiology.