The Government Is Unlawfully Detaining Vulnerable People in Removal Centres During a Pandemic

by Anna Highfield

7 May 2020

More than 400 detainees were released from UK Removal Centres (IRCs) at the end of March, in a panicked effort by the British government to contain the spread of Covid-19 – a pace of action unseen for years within the UK immigration detention system.

The release came in response to legal action against the government by Duncan Lewis Solicitors, which argued that the Home Office had failed to protect immigration detainees from the coronavirus outbreak by failing to identify those in at-risk categories.

It is estimated that a quarter of those currently in detention have been set free – but that over 900 people remain locked up.

Unlawful Detention.

Dunya Kamal, a trainee solicitor at Duncan Lewis Solicitors, is working to secure the release of all UK detainees based on a principle that has arrived from case law, which states that you can only detain someone if you can affect their removal within a reasonable time scale.

Using this, Kamal is calling for the release of everyone currently being detained. “Their detention is arguably unlawful because there is no reasonable prospect of removal because all countries have effectively shut their borders,” she explains. “The Home office can’t say that they can put one of our clients on a flight within a determined timescale, because that’s simply not happening across the board”.

Kamal points to recent action taken by the Spanish government, who released every migrant being held in the Barcelona detention centre in March, asking, “Why hasn’t that happened yet for us?… The more time that goes on the more risk there is for a real rapid spread across detention centres”.

‘A breeding ground for rapid spread.’

Kamal and her team have been building their case based on the opinion of expert epidemiologists. “The detention centres are a breeding ground for rapid spread – even more rapid spread – of the virus,” she explains, “due to the close quarters, the fact that often you’d be sharing a room with someone else”.

According to Kamal, the number of communal spaces in detention centres – particularly the dining areas and small courtyards – put everyone in detention at heightened risk, but especially people who fall into one of the at risk groups the government has put under lockdown for 12 weeks.

The Home Office has informed the firm that they will conduct a case-by-case review on every individual based on their vulnerabilities, and Kamal says they are now working to hold the department to account.

“There are many detainees held in these centres with a range of vulnerabilities,” she explains. “Some have subsisting health conditions, others are victims of torture, trafficking and suffer with mental health issues – they are extremely fearful of contracting Covid-19.”

Currently, the team is following up with all of their clients who are still in detention to see if they’ve been contacted by the Home Office. “There is still much work to be done,” says Kamal.

When approached for comment, a Home Office spokesperson said that the high court had ruled that the department “[is] taking sensible, precautionary measures in relation to coronavirus and immigration detention”. They maintained that the measures are “in line with the public health guidance” and “are in place to protect staff and detainees.”

They added:

“Public protection is paramount which is why we are working to maintain law and order and protect the public from high-harm individuals, which is why the vast majority of those currently in detention are foreign national offenders”.

When asked for the exact statistics on how many of those currently in detention are foreign national offenders the Home Office said they don’t publish those statistics or comment on statistics specifically.

High-risk for clusters of Covid-19.

The BMJ global healthcare network says the UK’s 10 detention centres are at high-risk for clusters of Covid-19, and that staff provide a dangerous bridge for infection to and from the community.

Two IRCs – Yarl’s Wood and Brook House – currently have confirmed cases of Covid-19, with symptoms reported at another, prompting rising desperation in refugee rights groups and healthcare charities, who are urging the Home Office to take action and release everyone in detention.

Retired Director of Public Health Hilary G Pickles warned of the disproportionate risk to detainees in a letter published on the BMJ website in March:

“As with all places of detention, those incarcerated in IRCs are denied control over many aspects of their lives. Cells and bathrooms are shared, outside space and fresh air limited, and cleanliness is difficult to maintain. Sustained and effective social distancing is an impossibility for all within IRCs. Many detainees are especially vulnerable due to their age, co-existing physical illnesses and, in a high proportion of cases, mental illness.”

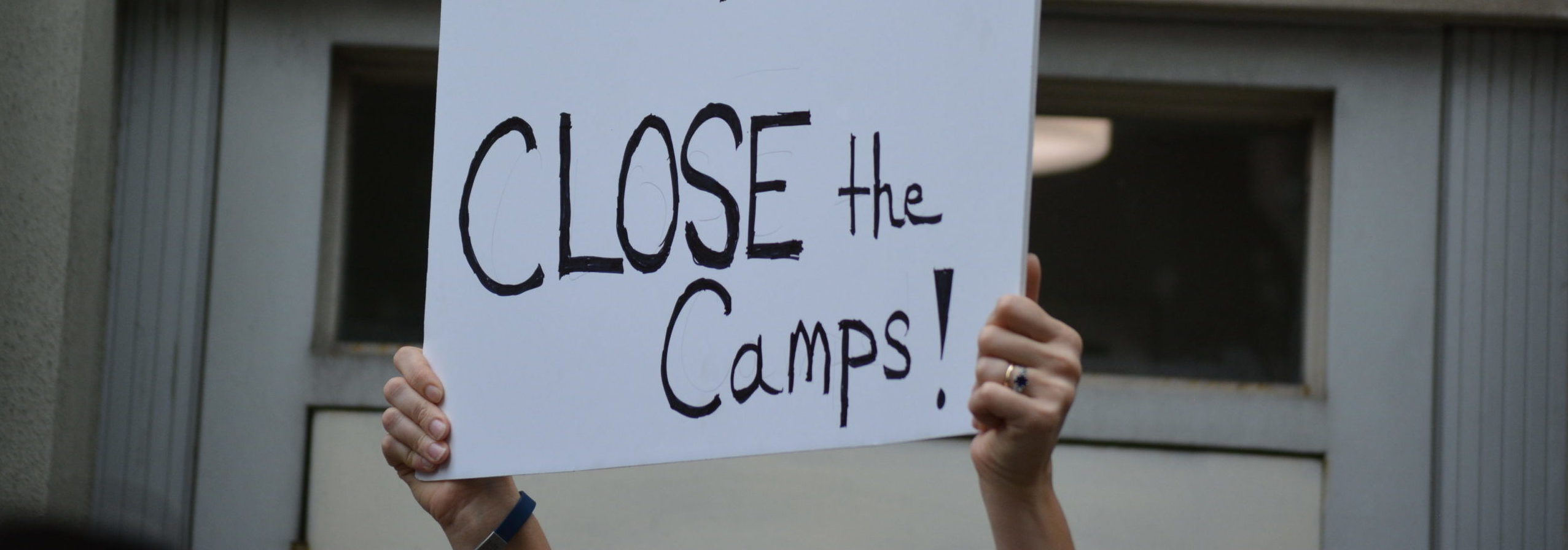

Voices calling for the release of detainees have included chair of the parliamentary group on immigration detention MP Alison Thewliss, health-rights group Medical Justice, campaign group Detention Action, the Association of Visitors to Immigration Detainees and Amnesty International, as well as a personal plea to home secretary Priti Patel from a group of ex-detainees.

‘A moral and humanitarian outrage.’

Ali McGinley is director of the Association of Visitors to Immigration Detainees, who is pushing for the “safe, timely and managed” release of everyone in detention.

She is worried that many of the centres don’t have adequate facilities to ensure proper quarantine and says the information provided to detainees has shown the government’s “callous disregard” for their wellbeing.

“People are telling us how hard it is to maintain even basic social distancing measures and that provision of things like hand gel and sanitiser is sparse,” she says.

And in the centres where cases have been confirmed she describes a rising climate of anxiety and fear. “We are hearing from people who feel they’ve been completely left behind as the rest of the UK works to put strict protection measures in place,” she says. “Continued detention at this time is really at odds with the calls for public health protection. It is a moral and humanitarian outrage that people are being left behind this way.”

Anna Highfield is a freelance journalist and environmental activist.