The UK is Not Innocent – Police Racism Has a Long and Violent History Here Too

by Wail Qasim

1 June 2020

“I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe.” This desperate refrain has once again become the dying words of yet another black man in the United States.

Memories of the New York City Police Department officer administering a lethal headlock on Eric Garner have barely faded since his death in 2014. In the years that followed, as protest and movement-building swept across North America, the words would come to take on their own life in solidarity with Garner and the countless other black men and women who have died following contact with the police.

It was haunting, then, to watch as George Floyd slowly suffocated to death under the knees of the Minneapolis police, making that same cry. “I can’t breathe” isn’t just a protest chant. It’s precisely what people call out when they are begging for you to spare their life.

Not just the US.

On a summer’s day in 2008, a 40-year-old black man named Sean Rigg died at the entrance of Brixton police station in London. The lead-up to his death would have looked in many ways like that of Floyd. With Rigg – who was in the midst of a mental health crisis – pinned to the ground, officers piled on top of his defenceless body, somehow able to ignore every basic instinct that tells a person not to allow a fellow human being to be crushed under their weight.

I was not there, nor do we have access to the same kind of footage of his death that we do in the case of both Floyd and Garner. However, it is not a stretch to imagine that as Rigg was pinned down by officers – for eight minutes – he too would have been calling out for his life, crying that he could not breathe. Instead of getting him the help he needed, he was dumped into the back of a Metropolitan police van, driven to Brixton police station and left to die in the caged area of the station’s custody entrance.

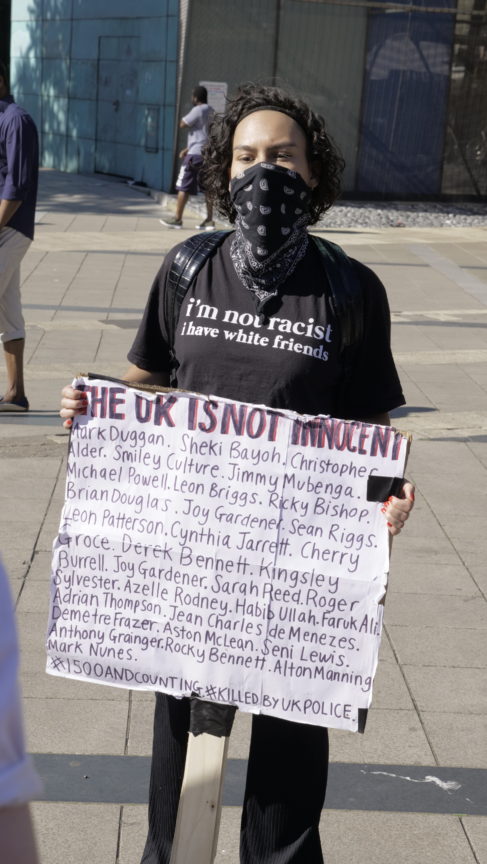

Despite ongoing campaigning, the Rigg family have yet to see an officer convicted for his death. In fact, according to the charity Inquest, 1,741 people have died in police custody or otherwise following contact with the police in England and Wales since 1990. Not a single police officer has been convicted in connection to these deaths.

We’re gathered outside Brixton Police station, to mark the death of Sean Rigg. 8 years and no justice! #Justice4Sean pic.twitter.com/7xFfqOEhVE

— aadam (@AadamMuuse) 21 August, 2016

Campaigning groups also highlight that BAME people are disproportionately represented in those deaths involving the use of force or restraint. Of the 74 people fatally shot by police since 1990, 20 of those people have been BAME, meaning those communities are proportionately twice as likely to be shot dead by an officer. The UK certainly has its own case to answer for regarding police brutality, and the inherent racism that underpins it.

Indifference is a weapon.

While it’s often suggested that the weapons carried by officers in the US – along with the advanced militarisation of US police forces – are to blame for the countless deaths of black people across the country, this explanation is overly simplistic and ignores the deeper systemic issues at play.

It is abundantly clear that officers in the US are trigger happy. We need look no further than to another death in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota – that of Philando Castille. In 2016, the livestream video of Castille’s killing was posted to Facebook by his partner Diamond Reynolds. After being pulled over as part of a traffic stop, the 32-year-old was shot fives times in front of Reynolds and her four-year-old daughter. This happened after Castille warned the officer he had a firearm in his car and was not reaching for it.

But unlike Castille, it took no weapons or militarised equipment to end Floyd’s life, simply an indifference to his humanity. That indifference, so often founded on racism, is a deadly weapon not exclusive to nationhood and is shared by police forces across the UK.

This was demonstrated in Scotland in 2015, when Sheku Bayoh died in hospital after being sprayed with tear gas and restrained by police. As a result, he suffered a fractured rib and bruising across his face and body. One of the officers involved would later be accused by his own brother-in-law of hating black people, and like the Rigg family before them, the Bayoh family continue to wait for justice.

There are those too who have suffered similar police restraint and survived. The deaths we see in police custody are only the most lethal examples of the everyday brutality of racist policing. The deeper story is one of communities subjected to greater criminalisation, officers stationed permanently in schools and the continued disproportionate use of stop and search against people of colour.

On Sunday morning, Shola Mos-Shogbamimu shared a video on Twitter of a young woman being restrained by what appears to be six police officers, one of whom seems to be punching at her on the ground. Once again, we hear those all-too familiar words: “I can’t breathe”.

.@metpoliceuk why would it take SIX Police Officers to PIN down ONE WOMAN in Lewisham? I can see Police hitting her as she screams I can’t breath? Shouting ‘Please STOP’ as she’s being slapped! She’s restrained!

This is Unjustified Unacceptable Excessive Force #PoliceBrutality pic.twitter.com/UbB6g3nw4Y

— Dr Shola Mos-Shogbamimu (@SholaMos1) 31 May, 2020

The event took place in Lewisham on Friday evening, after police had covered the area with blanket powers afforded by Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994. These powers allow for indiscriminate searches in targeted locations – and most often this targeting is of communities in which racialised people live in greater numbers.

When police brutality in the UK is protested, a common response is that policing is proportionate to greater criminality and serious violence in certain areas. This claim was in fact used to loosen controls on Section 60 searches by former home secretary Sajid Javid last year.

Repeated reference to the supposed criminality of areas populated by black and other people of colour is a distraction. By creating this association, the UK offers up its own version of the ‘black-on-black crime’ myth, suggesting that increased police presence and powers are for a community’s ‘own good’.

Where serious violence does affect the lives of people of colour, they face yet more violence at the hands of the criminal justice system. Being disproportionately imprisoned, brutalised and killed destroys any notion that police are there for our protection.

A shared history.

The murder of George Floyd is the latest in a long history of police racism and brutality in the US. In the UK and internationally we’ve seen an outpouring of empathy, with many taking to the streets to join people in the US in protest and in mourning.

But if empathy is to evolve into a deeper, more fundamental understanding of why people of colour are dying at the hands of the police, we must look closer to home. We must learn the stories of Sean Rigg, Sheku Bayoh, Mzee Mohammed, Leon Patterson, Cynthia Jarrett, Joy Gardner and the many others who have died following their contact with British law enforcement.

I take no comfort in the fact that police brutality seems worse in the US. My siblings’ sufferings will not save me. On both sides of the Atlantic, black and other people of colour continue to breathe their last with no justice in sight. As awful as it is, we must acknowledge that this is our shared history.

Wail Qasim is a writer and anti-racist campaigner based in London.