Black Britannia: Today’s Anti-Racist Movement Must Remember Britain’s Black Radical History

by Bryan Knight

18 June 2020

Days after the police murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement resurged with global momentum.

Protesters all over the world have taken to the streets to protest police racism and brutality, and to demand change.

In Britain, the BLM movement has exposed the country’s widespread colonial amnesia, along with a cultural reluctance to self-reflect. Fortunately, a significant number of Britons have shown solidarity with the American movement, reigniting a much-needed dialogue around race.

The recent toppling of statues in the UK and across the world demonstrates the importance of engaging with colonial histories. However, it is vital that we remember not only tales of oppression but also ones of resistance, honouring and learning from our anti-racist predecessors and situating the current resistance within the broader struggle for equality.

Today in Britain, Black communities face institutional racism, police brutality and chronic community underfunding. 50 years ago, Black Britons were fighting these same evils. Indeed, it was in this same context that Black radicalism found ground in the 1970s.

Taking inspiration from their American counterparts, young British radicals formed collectives and organisations in defence of their community. In 1968, Eddie Lecointe, Peter Martin and Nigerian playwright Obi Egbuna founded the British Black Panther movement. Egbuna went on to write Destroy This Temple, which served as his Black Power manifesto.

Following Egbuna’s departure, Altheia Jones-Lecointe became the de-facto leader. Under her leadership, the Panther movement took direct action against the police, and, in the process, successfully challenged the brutality of the Metropolitan Police and the British state.

The Mangrove Nine trial was a landmark moment in transforming racial justice in the UK, serving as both a victory for the Black community and an embarrassment for governing institutions.

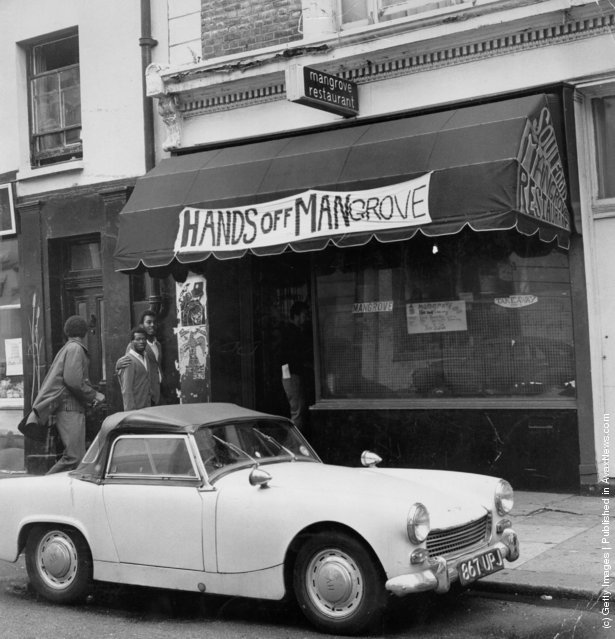

The trial focussed on the police harassment of the Mangrove restaurant in west London’s Notting Hill area. Owned by Frank Crichlow, a Trinidad-born community activist who was known in London as a godfather of Black radicalism, the Mangrove was the heart of the Caribbean community, known to attract both Black and white radical thinkers.

Due to Critchlow’s high profile in Notting Hill, police, led by corrupt officer Frank Pulley, raided his restaurant 12 times between January 1969 and July 1970, describing the Mangrove as not only a drug den but also a haunt for “criminals, ponces and prostitutes”.

As a result, London’s Black community joined forces with the Panthers to demonstrate against police harassment.

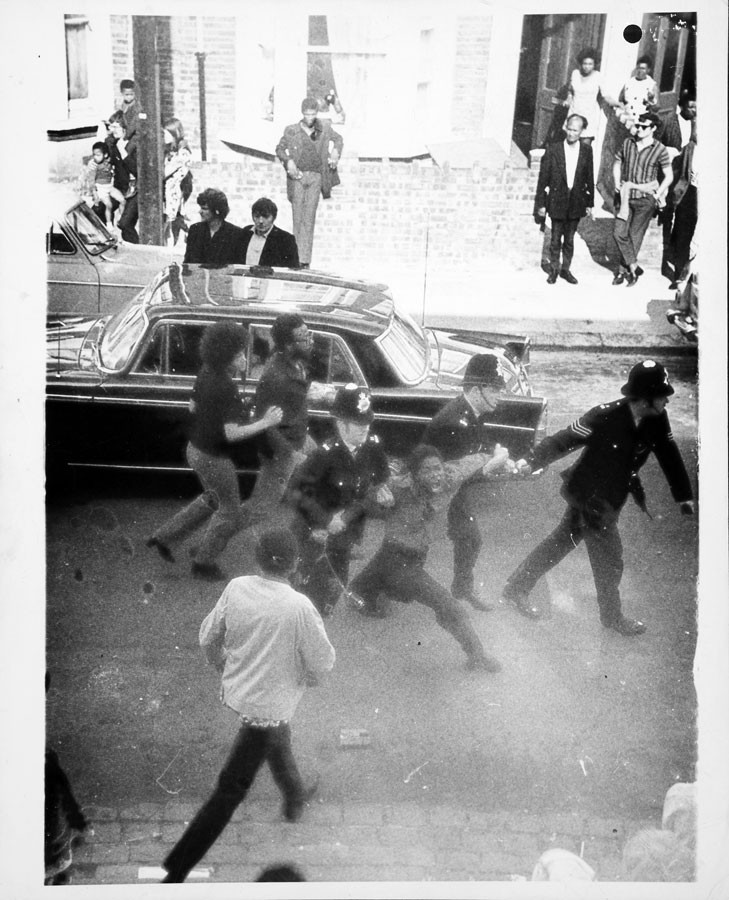

Armed with anti-racist placards and chanting for Black liberation, the demonstrators marched to three local police stations. But what started out as a peaceful protest soon intensified into a violent confrontation, after demonstrators were met with two hundred officers “lined in military formation”, as Darcus Howe, one of the Mangrove Nine, recalled.

It would later be known that the Black Power Desk, a surveillance group in the Metropolitan police’s Special Branch, covertly collected information on the Panthers before and during the demonstration. The Met’s meticulous surveillance of the group spoke to the Panthers’ ability to pose a real challenge to the racist state.

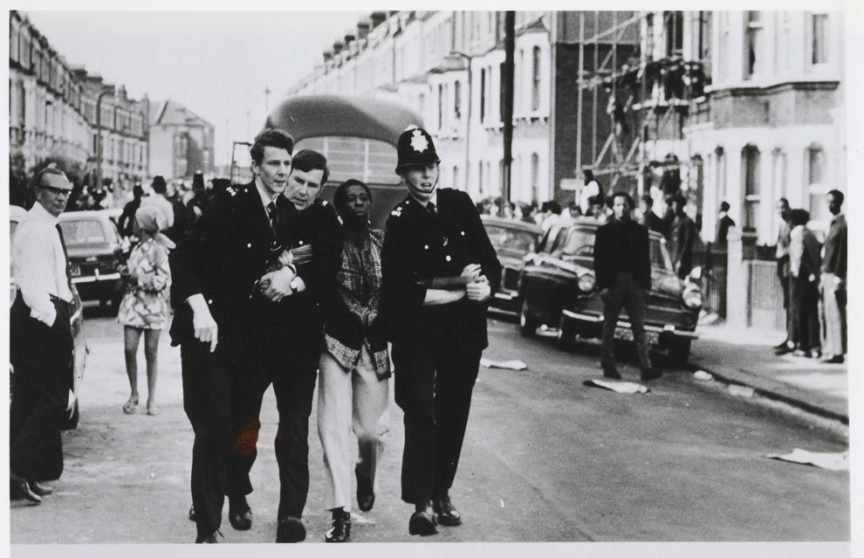

According to the National Archives, photographs like the one pictured above were “used by the police to suggest that key allies of the Black Power movement were implicated in planning and inciting a riot”.

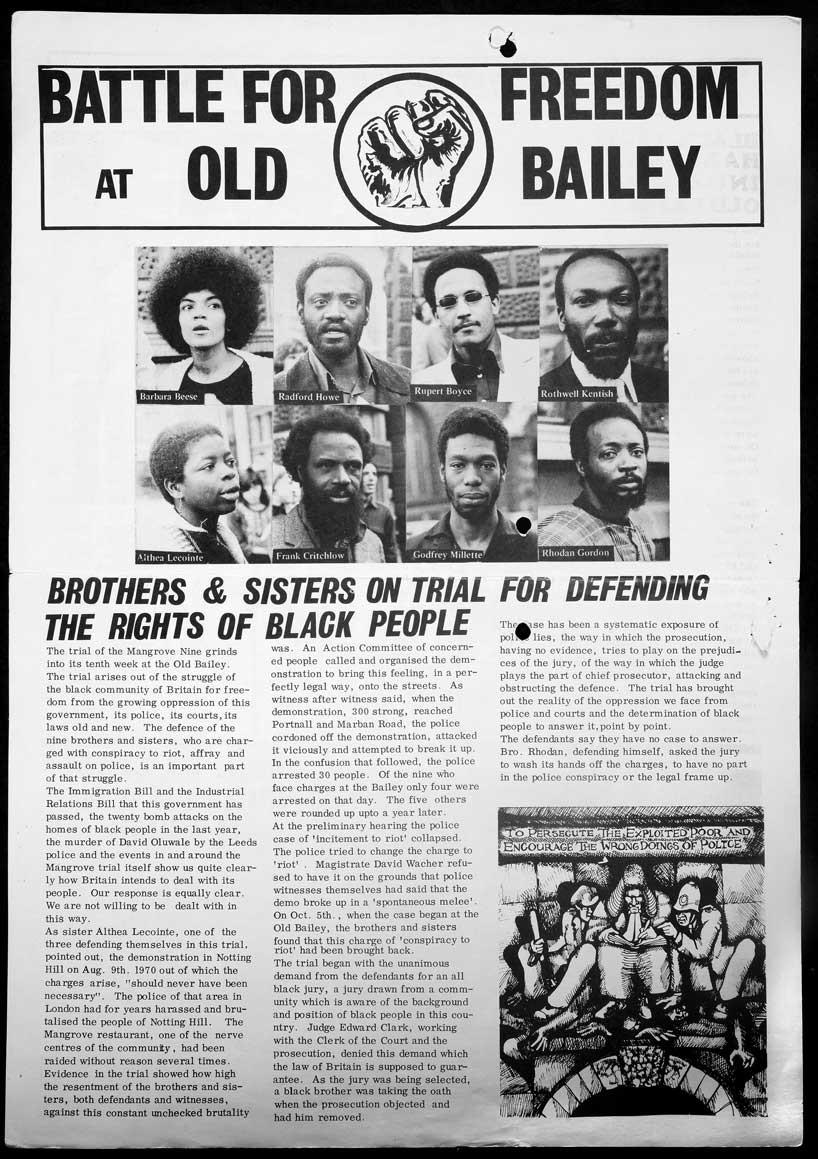

Facing a total of 32 charges, the most serious being incitement to riot, were Barbara Beese, Rupert Boyce, Frank Crichlow, Rhodan Gordon, Darcus Howe, Anthony Innis, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Rothwell Kentish and Godfrey Millett – a mix of both Black Panther members and other community activists.

During the trial, the defendants came up with an effective strategy that honoured the tenets of Black radicalism: self-representation.

Both Jones-Lecointe and Howe took the unprecedented decision to defend themselves, whilst radical civil rights lawyer Ian MacDonald QC helped synchronise the legal defence of the Nine.

The group met regularly during the 55-day trial, studying key texts by Black intellectuals such as C.L.R James and Walter Rodney. In a 1973 documentary, the Nine emphasised the importance of taking a comprehensive approach in building their defence, linking their struggle with those being fought by African Americans and also Black nationalists in the colonies.

Despite their request for an all-Black jury being denied, the Nine strategised a way to get through to the white working-class jury members.

In the documentary, MacDonald spoke about how the defendants invoked the history of transportation in Britain. This line of argument was used to illustrate how the establishment had historically devised ways of punishing and suppressing the working class. The Nine went on to attack the layout of the courtroom, pointing out the disparate class divisions that existed between the jury and the judge, who presided at a higher post.

By rooting their argument in class struggle, the Nine was able to demonstrate how the racist, capitalist system not only oppressed Black Britons but the working class more broadly; that, ultimately, this was a shared struggle.

The fight for the Nine to go free was a concerted effort, which relied on the support of other groups such as the Black Liberation Front, Black Freedom and Unity Party and the Racial Adjustment Action Society. These Black power groups united in solidarity with the Nine, along with allied media publications, by attending subsequent demonstrations and raising funds for the defence.

In a shock outcome for both the defence and the prosecution, the jury sided with the Nine in accepting that there was no attempt to incite a riot or violent altercation. The verdict led the judge to take the unprecedented step of acknowledging racial prejudice in the Metropolitan police.

The trial’s outcome was unprecedented, not only in exposing racism within state institutions, but also leading to the enactment of drastic legal reform.

The Nine not only succeeded in defending the rights of Black people, but they also transformed British jurisprudence.

Whilst the verdict was a huge victory for the Nine, giving credibility to the Panthers as a group and legitimacy to the wider cause, it also, unfortunately, led the state to tighten its reins to prevent similar challenges to authority. For example, new measures were introduced to limit the powers which defendants could exercise during court proceedings.

Today’s generation of anti-racists must remember and learn from those who fought and made gains in fighting discrimination in prior decades. Despite the British education system’s failure to teach this anti-racist history, it is our collective responsibility to fill the gaps in our knowledge.

We stand on the shoulders of those who paved the way for us. The Mangrove Nine succeeded in their mission by seeing the bigger picture and understanding that all forms of oppression are linked. Reflecting on the solidarity shown by other organisations highlights the urgent need for activists and industries to unite in the face of today’s fight against racism.

In order to find tangible solutions and maintain the momentum for change, it is vital we recognise the importance of self-reflection and self-education.

Bryan Knight is an oral historian and journalist based in London. He hosts the Tell A Friend podcast, discussing current affairs and historical topics.