Trump’s Attack on ‘Anarchists’ Is Just the Latest Red Scare

by Ruth Kinna, Matthew S Adams and Thomas Swann

10 August 2020

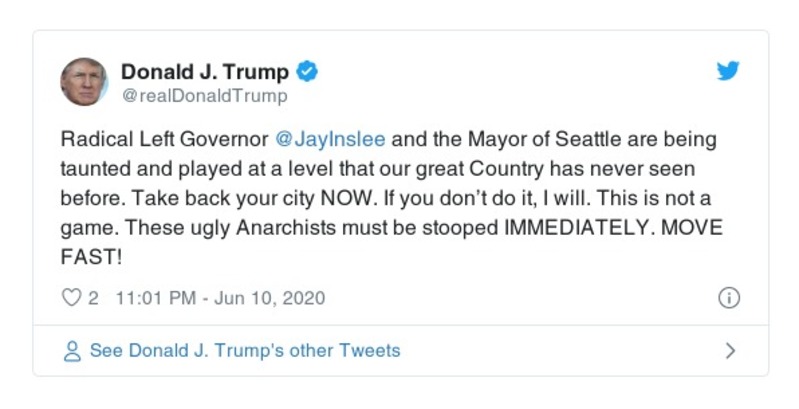

Diplomacy conducted by the late-night glow of an iPhone screen has become a hallmark of Donald Trump’s presidency. On 10 June, he turned his attention to “ugly anarchists” in Seattle, urging Washington’s governor Jay Inslee to get to grips with the insurgent threat and ‘take back your city NOW’.

Trump’s alarm about “anarchists” signalled a new turn in his polarising administration. Since the mobilisations sparked by George Floyd’s killing by Minneapolis police, the Trump team’s references to “violent anarchists” have formed a core foundation for their law and order strategy. Since mid-July, the warnings of “deranged anarchists and agitators” running wild have given a green light to the US department for homeland security to deploy unmarked snatch squads to hoover up protestors from the streets. With Trump recently threatening to send a surge” of law enforcement officers into Chicago, Joe Biden has even jumped on the bandwagon and called for anarchists to be prosecuted.

Politicians on both sides of the political spectrum usually play with law and order agendas in the run-up to elections. But Trump’s “ugly anarchists” (and its echo in Biden’s threat of prosecution) speaks to a history of red scares.

Politicians on both sides of the political spectrum usually play with law and order agendas in the run-up to elections. But Trump’s “ugly anarchists” (and its echo in Biden’s threat of prosecution) speaks to a history of red scares.

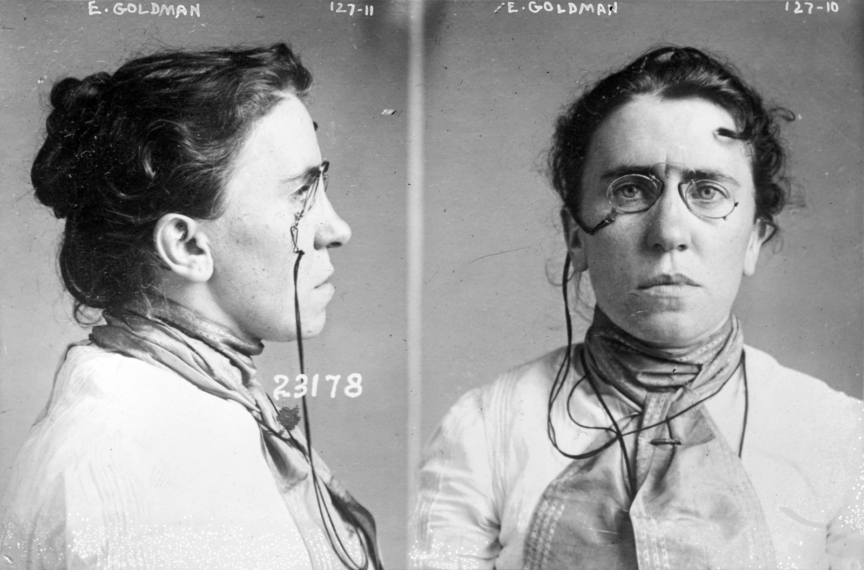

In the 1920s, Jewish and Italian immigrants were deported in their thousands. Among them was Emma Goldman, described by FBI head J Edgar Hoover as one of the “most dangerous people in America”. In roughly the same period, anarchists Joe Hill, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were executed. There was no hard evidence against them, nor against the Haymarket Anarchists – Chicago labour leaders executed in 1887 – whose activities sparked the first red scare.

Apart from reminding us of some obvious injustices, resurrecting this history points to the ideological value of the label. “Ugly anarchists” is a call to conservatives to protect America from its ‘enemies’. After rounding up ‘un-American’ Europeans, Hoover went after civil rights activists. Repeated without challenge in the mainstream media, the spectre of anarchism – standing for all that conservatives and even many liberals fear most – reinforces the strategic demonisation of movements that expose and mobilise against persistent injustices. No wonder Trump resurrected it when Black Lives Matter took to the streets.

“Ugly anarchists” distracts from the creativity of resistance and dissent. Standing in the dock, the Haymarket anarchists told the jury that Webster’s dictionary carried two definitions: anarchy meant “without rulers” or “disorder and confusion”. Their idea anticipated the “beautiful ideal” that Emma Goldman professed: a release from “conventions and prejudice” and a bold assertion of “everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things”. Trump’s snatch squads, a continuation of the measures deployed against undocumented migrants, are a manifestation of the other – the truly ugly presence in American politics.

Trump is the latest in a long line of presidents who view anarchism as an alien presence in American life. His “ugly anarchists” bluster mischaracterises the organisational experiments at work in the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone in Seattle. For the activists involved, this kind of experiment reflects fundamentally American values and political principles. But as Paul Goodman, the pioneering social theorist of the 1960s argued, the ‘anarchist picture’ of American history had been written out in favour of a story of state centralisation and professionalisation.

Anarchists see the “beautiful ideal” in the attempts by Makhnovists to liberate Ukraine from the domination of both the new Bolshevik government and Tsarist counter-revolutionaries; in the actions of the CNT and FAI in Spain that saw much of the industry and agriculture brought under the control of workers; and more recently in the autonomous communes of Rojava that continue to face down ISIS and the Turkish state.

In everyday life, this “beautiful ideal” comes to the fore when communities come together to look after themselves without recourse to government or other forms of centralised control, such as in the mutual aid groups that have formed in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. In these examples and countless others, anarchy is realised by people acting collectively and practising solidarity, without direction from above and the mediation of leaders or politicians.

Trump and others find these experiments in anarchy disorderly and confusing, but the important point here is the designation of popular demands as “ugly”. It brooks no opposition to conservatism. Anthropologist James C Scott writes of the tendency in modern states towards legibility and control. Populations have to be understandable and categorisable by state bureaucracies so that they can be manipulated in the name of supposedly higher goals.

One of the strengths of anarchism – particularly its recent engagements with intersectionality theory – is in showing how this drive for conformity and control intersects with economic exploitation and domination along lines of class, race, gender, sexuality and more. If we “see like a state”, as Scott puts it – or see like systems of capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy and state domination – then anarchist practice is indeed ugly.

Those active in the Black Lives Matter movement, the Me Too movement and other mobilisations see beauty in them. They are not all anarchist but their attempts to bring about change speak to the “beautiful ideal”.

Lucy Parsons, a Chicago activist and Haymarket widow, was described during the red scare of the 1920s as “more dangerous than a thousand rioters”. It sounds ugly. But when we hear these assertions, we need to remember the history. That history tells us that the real ugliness of American politics comes from the law and order agendas that Trump and his forebears champion, and not the beauty in attempts to resist them.

Matthew Adams, Ruth Kinna and Thomas Swann are members of the Anarchism Research Group at Loughborough University. Matthew edited the Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism (2019) and is co-editor of the journal Anarchist Studies. Ruth is author of Great Anarchists’ (forthcoming with Dog Section Press and The Government of No One (Pelican Books, 2019). Thomas is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow, author of Anarchist Cybernetics (Bristol University Press, 2020) and co-editor of Anarchism, Organization and Management. Critical Perspectives for Students (Routledge, 2020).