After 600 Days of Political Deadlock, Why Isn’t Belgium Facing Civil Unrest?

by Hannah Robinson

25 August 2020

Earlier this month, Belgium broke its own record for the longest period a country has gone without an elected government in peacetime. In December 2018, the country’s federal government collapsed when the right-wing Flemish nationalists, the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), left Charles Michel’s four party coalition after the signing of the UN migration pact. It has now been more than 600 days since the coalition fell – a record being tracked by an online counter.

A nation in limbo.

The May 2019 election threw Belgian politics into crisis. Handing victory to the nationalist right in Flanders, N-VA, alongside the extreme-right party Vlaams Belang, received almost half of all votes. In Wallonia, the far-left Workers’ party (PTB/PVDA) and the Greens both increased their vote share, and the Parti Socialiste (PS) remained the largest party. Reflecting global trends, the traditional centre was squeezed and parties at the fringes broke through. In a political system that depends heavily on consensus, voters gave politicians from highly opposing parties the difficult task of working together to form a coalition.

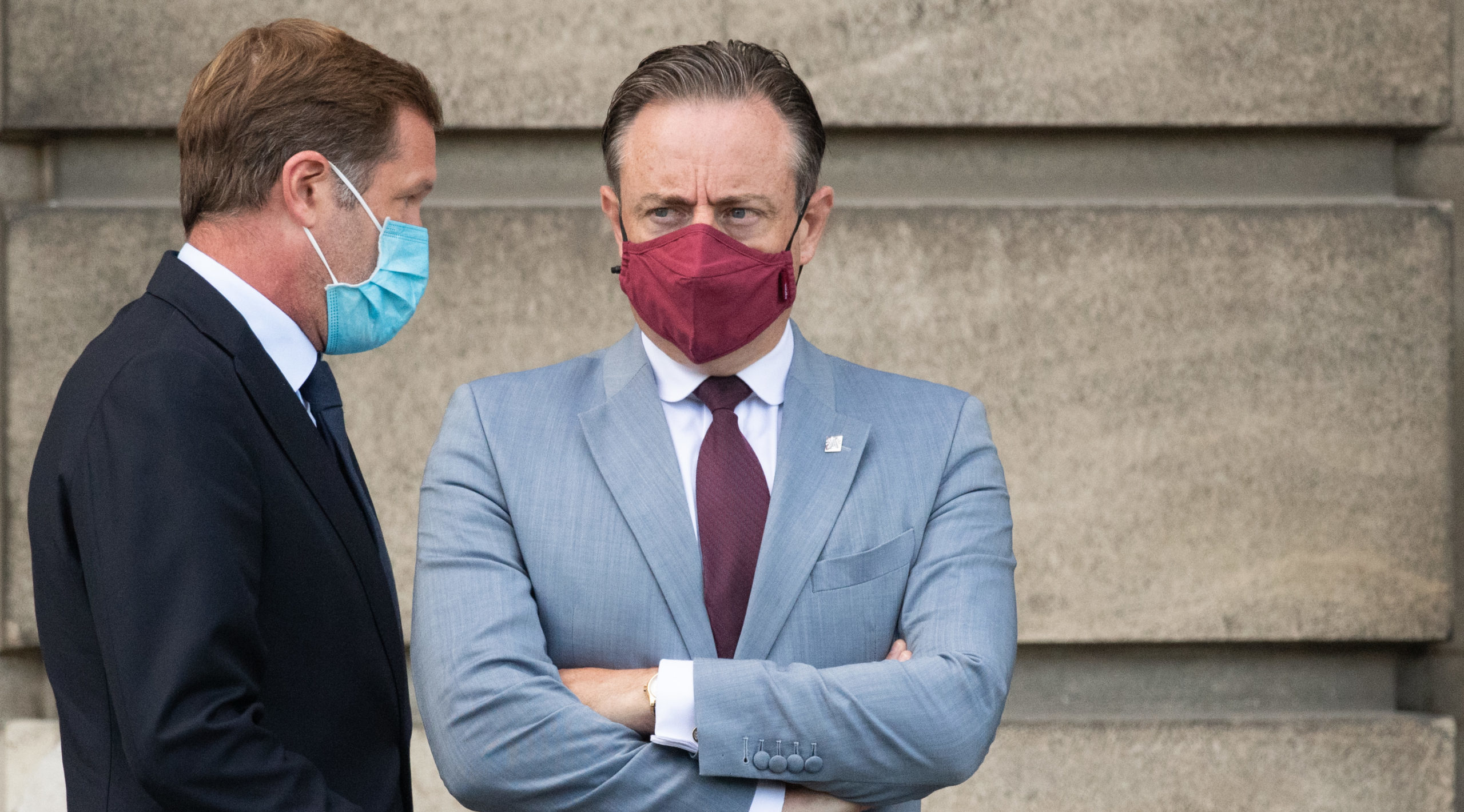

Despite only coming fourth in the 2019 elections, the French-speaking liberal Reformist Movement (RM) that led the former coalition government was given a caretaker mandate to govern the country. Emergency powers were extended to this government to manage the coronavirus crisis, but talks have now resumed to find a functioning long-term coalition. The socialist PS and nationalist N-VA had formed an unlikely duo in an attempt to achieve this, but last week talks collapsed. The task now falls to Egbert Lachaert, leader of the Flemish liberals Open VLD, and the twelfth person since May 2019 appointed to solve the impasse. A so-called ‘Arizona coalition’ of nationalists, socialists, liberals and Christian Democrats is at present the most plausible coalition, but every day poses new challenges. With a vote of confidence due to be held on 17 September, it is looking increasingly likely that Belgium will have to go back to the ballot box.

In another country, an absence of government for such a long period might potentially lead to civil unrest. For now, in Belgium, daily life continues as normal. Why?

Division and cooperation.

To understand how the country holds together without a government, we first need to understand the make-up of Belgian politics. Divided into three regions – Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels – the country has six governments and three national languages (Dutch in Flanders, French in Wallonia, and German in a smaller enclave in the south east).

Due to Belgian political structures, economics, languages and a split media landscape, a power struggle exists between Flanders and Wallonia. Deindustrialisation has left Wallonia much poorer than Flanders, with almost double the levels of unemployment. Whilst nearly 60% of Dutch speakers speak French, less than 20% of Belgium’s Francophone population speak Dutch. In recent years, the gulf between the Flemish and Francophones has widened, with increased Flemish calls for autonomy.

As political scientist Arend Lijphart has put it, what’s remarkable about Belgium is “not that it is culturally divided […] but that its cultural communities coexist peacefully and democratically”.

There are a number of factors that have facilitated this. One is Brussels. Home to key EU institutions and NATO’s headquarters, Brussels is a significant employer of people from across Belgium’s regions. Although surrounded by Flanders and historically a Dutch-speaking city, today Brussels is essentially a French-speaking city. Both regions view Brussels as their capital, and as such breaking up Belgium would be of considerable cost.

Another factor contributing to stability in Belgium is that power in the country is heavily decentralised. Federalisation, which took place from the 1970s to the 1990s, was designed to pacify increased tensions around calls for regional autonomy. Whilst this has meant longer-term policy decisions at a national level are harder to make (which has in turn led to calls for even greater regional autonomy), it has also meant that in times without a federal government, local and regional governments can continue to function, and life can carry on with relative normality.

What’s more, Belgian democracy exemplifies what’s referred to as ‘consociationalism’ – a form of power-sharing found in societies that are divided or segmented, either socially or ethnically. Because political stakes are higher in divided societies, as there is greater potential for a breakdown, representatives must work together to achieve political stability. Instead of as a zero-sum game, common ground must be found. One example of this in Belgium has been the cordon sanitaire – an agreement whereby since the 1990s parties have excluded Vlaams Belang from any coalitions in order to protect democratic values.

The Belgian system, whereby different parties strive to cooperate, stands in stark contrast to the tribal electoral system which exists in the UK. Whilst it can be refreshing to see compromise and coalitions at the heart of politics, the Belgian system clearly has its downsides – not having a government for half the time being the main one.

Can the system hold?

Polls suggest that if elections were held today, Vlaams Belang and the PTB/PVDA would improve on their results from 2019 – likely because these parties aren’t part of the current coalition, which is deemed to have botched Belgium’s coronavirus response. The fear amongst many is whether the cordon sanitaire will still hold if Vlaams Belang win more votes, whilst development towards an even more federalised system and increased cries for separatism could be the next steps should both Vlaams Belang and N-VA increase their vote share. Already negotiations between PS and N-VA – whereby the parties agreed on a starting point of a more leftist economic approach in exchange for state reform, with a federal government in place for two years instead of five – have hinted at this path forward.

Throughout Belgium’s recent history, political compromises, often reached in unprecedented ways, have succeeded in maintaining the country’s political system. Parties’ willingness to cooperate at the federal level increased at the start of the coronavirus crisis, inspiring hope for breaking the current political impasse and finding a functioning long-term coalition. This hope, however, has since faded, and with the economic fallout from coronavirus likely to deepen economic disparities across the country, polarised positions may become more entrenched. If a government can’t be formed to break the political deadlock, there could be a rocky road ahead.

Hannah Robinson works for a peacebuilding organisation based in Antwerp.