Italy’s Migrants Are Being Attacked From Left and Right. They Aren’t Going to Take It Lying Down

by Alice Figes

7 September 2020

As regional elections approach later this month, and with a second wave of coronavirus expected shortly thereafter, the Italian far right and centre are engaged in a race to the bottom on immigration. This xenophobia has long historical precedent – though so does the resistance to it.

“Italians are being held hostage,” Matteo Salvini, leader of the Lega party, declared last month to an applauding crowd in the port city of Livorno. “Thousands of balordi [thugs] are arriving: they do what they want, go where they want, spit, infect. Enough.”

Italy has received 17,985 migrants so far in 2020, the highest number of any EU country. The vast majority come from either Tunisia, a country in economic crisis, or Libya, a state in civil war. Now, the country’s far right hopes to make gains by blaming migrants for coronavirus. So far, it’s working: Lega currently leads the polls in Italy by a large margin with 24.6%, while Giorgia Meloni’s neofascist party Brothers of Italy has risen to 15.3%.

In reality, the impact of new migrants on Covid-19 in Italy has been minimal. Less than 5% of new infections registered in the first two weeks of August were migrant-imported. In fact, the data suggests that a significant number of cases came from tourism: 25% came from Italians returning from holiday. Young, asymptomatic carriers in social settings seem to pose the greatest risk, a fact corroborated by the government’s recent decision to shut nightclubs.

But it’s not just the far right who are cynically stoking anti-migrant sentiment. The ruling Democratic party (PD), which evolved out of the Italian Communist party, has begun to pander to the “Fortress Italy” populism of the far right. The party caused outrage in 2017 when it voted to fund the Libyan coast guard, turning a blind eye to its human rights abuses, which include rape and torture.

More recently, in a bid to limit far-right gains in September’s regional elections, Luciana Lamorgese, the PD’s newly-appointed interior minister, called new boat arrivals “unacceptable”, initiated draconian two-week ferry quarantines, and employed the army to patrol Sicily. These punitive policies came in spite of expert warnings that they would likely increase the risk of a second outbreak, and laying out safer (and cheaper) temporary measures.

Lamorgese’s plans have already backfired: unsafe overcrowding in migrant “welcome centres” has inevitably led to mass escapes, such as in Agrigento, Sicily, where fifty migrants broke out in July, where 650 people were being held in a space designed for 95. A few days ago, a 20-year-old Eritrean man was run down and killed after trying to flee a similarly overcrowded centre, where he’d been held since 1 August.

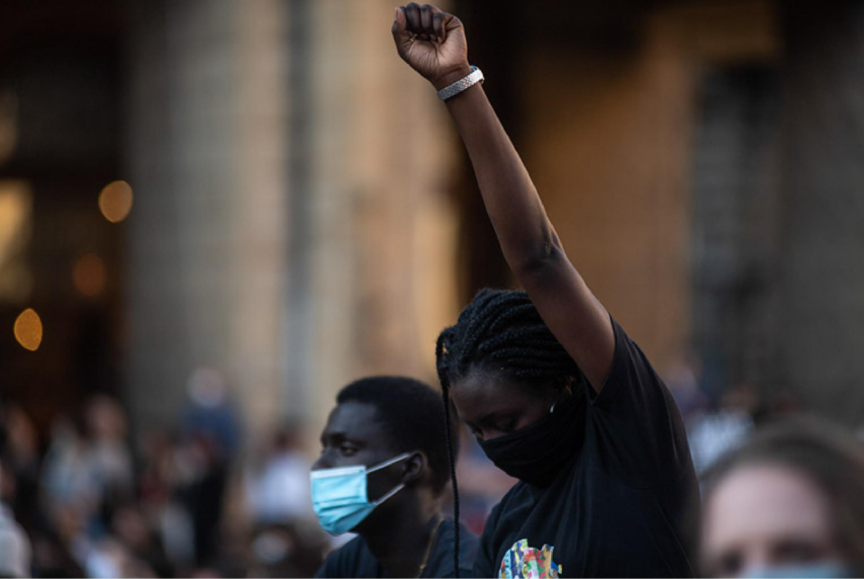

Many Italians say the real issue is limiting the spread of the virus in these centres, where residents are forced to share windowless rooms with up to 12 other people. In July, Bologna Black Lives Matter (BLM) and Bologna Coordinamento Migranti (BMC) protested for the closure of Mattei centre – an ex-prison on the outskirts of Bologna, now an incubator for Covid-19 – following a huge outbreak at the logistics firm Bartolini, where a number of Mattei’s 250 residents were working. Despite urgent calls to rehouse the migrants, the government has failed to offer anything more than tests.

“Migrant men and women are always in quarantine,” said Orkide, a Kurdish migrant and PhD-student who arrived in Italy in 2006, at the July demonstrations in Bologna. “Covid-19 is just a magnifying glass.” Italy’s migration problem is twofold: not only must it handle the wave of new arrivals sweeping the whole of the EU, but it must protect and integrate “invisible” migrants who have been living and working in Italy for years.

Salvini’s security decrees.

Under Article 10 of the Italian Constitution, asylum-seekers fleeing countries of war, dictatorship or discrimination can be granted five-year residence permits. Before 2018, a two-year “humanitarian pass” was also available to ‘economic migrants’ or those fleeing due to personal stories of discrimination. But when Salvini came to power, dramatically shutting down Italy’s borders, he axed it with the introduction of so-called “Security Decrees”, which UN experts complained violated human rights. (Last week, after years of shadowboxing, the government finally pledged to reverse some of the Security Decrees’ more harmful aspects.)

Today, when migrants make the request for asylum, they are granted a maximum six-month residence permit while they wait to hear back from the commission. The vast majority of these requests for asylum are rejected – in Salvini’s first year of power, asylum acceptance dropped by 21% – forcing applicants off-grid to survive. For those still waiting to hear back from the commission (a process that can take up to 3 years), their permits are renewed automatically.

Whilst this renewal system may appear favourable to migrants, this couldn’t be further from the truth. Employers are reluctant to hire migrants on six-month permits, blocking them from contracted work. Subsequently, they are forced into contratti a chiamata (on-call labour) and the worst forms of labour exploitation, including underpayment and dangerous working conditions.

The pandemic exposed how much Italy depends on this informal labour. In May, the country’s agricultural sector almost collapsed once the 400,000 migrants and refugees who work in it went into lockdown. Many migrants in crucial sectors – hospitals, freight, delivery – continued working regardless.

For these workers, said Attilia, a 25-year-old second-generation Ghanaian-Italian, “Every day at work is a risk”. Attila was born in the province of Vicenza, and now studies law at the University of Bologna. She’s an active member of her local BLM group, and spoke at last month’s demo. “Who would work at night for 10-12 hours, for €4.50 an hour? Who? Nobody. It’s easier to call the migrant who has just got off the boat, the desperate person tossed from one city to another.”

Salvini’s governance also exacerbated the harmful impact of the Bossi Fini legislation of the early 2000s, which linked residency permits (permessi di soggiorno) to contracted work, as well as fixed housing, leaving migrants in a vicious cycle: without a secure job, securing housing becomes impossible, since landlords require proof of income. Migrants, therefore, represent a large proportion of Italy’s homeless.

A culture of racism.

Migrants who clear this bureaucratic hurdle must contend with Italy’s pervasive culture of racism.

“I have always respected the rules,” said Abdi, 21, who escaped Guinea in 2017, aged 18. “I went to school, I got my driving license, I attended compulsory courses, I learned Italian fluently – basically everything they told me to do”. Abdi arrived in Italy on the two-year humanitarian pass, shortly before it was scrapped. When his permit expired, however, he was left unable to secure a work contract or a residency permit. Consequently, his asylum request was rejected. He has since appealed and is waiting to hear back.

During lockdown, Abdi secured a contract with food service firm GSI. Yet upon entering the workplace, he discovered that jobs are first allocated to the white workers, then north African employees, with black employees lucky to receive what’s left. Meanwhile, Abdi still can’t find a place to live in Bologna, since most landlords refuse black tenants.

Bologna is a case study in the rightwards shift of Italian politics. The city was once Italy’s antifascist, communist heartland, and the birthplace of the anti-Salvini sardine movement. Bologna’s Emilia-Romagna also takes the second-highest number of migrants in Italy after Lombardy. Today, however, luxury redevelopments are being built over sites of historic and contemporary leftism, while the city centre fills with designer malls catering to an international, transient elite. Last year, XM24 – a famous occupied former-market-turned-social-center, offering free Italian lessons to migrants – was evicted by the PD government, triggering a protest that saw ten thousand people from all over Italy descend upon the city.

In the absence of state support (and in the face of outright state hostility), the fight for migrants’ rights in Italy has largely been left to grassroots groups, who also seek to educate against Italy’s rising wave of cultural racism. One such group is BMC (Bologna Migrant Coordination). Founded fifteen years ago, BMC is “a collective of both Italians and migrants” from countries including Guinea, Tunisia, Turkey, Syria and Pakistan, plus former Italian colonies such as Libya and Eritrea. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in the US and the international explosion of the BLM movement, BMC has joined forces with Bologna’s BLM group to campaign around not only migration but growing negrofobia (antiblackness), too.

“What does it take to feel at home in this country?” asked Anthony, a 30-year-old, second-generation Italian and member of Bologna BLM, of the crowd in Piazza Maggiore. Anthony was born in Nigeria but moved to Venice at 14 with his siblings to join his mother. After graduating with degrees in human rights and international relations from Padua University, he worked for the UN; he currently works for an NGO in Bologna. “But no matter how integrated you are,” he said, “there’s always a limit”.

As if to prove his point, only moments later, his speech was interrupted by a white, middle-aged passerby, who marched to the front of the crowd and attempted to snatch the microphone. “Italians aren’t racist. Not everything is about race,” he declared. “It’s offensive.”

Denial and historical negation.

“People don’t want to say the word racism in Italy, let alone talk about it,” Italian journalist Nadeesha Uyangoda said recently. The stereotype of all Italians as warm, welcoming brava gente (great people) somehow supports the idea that Italians can’t be racist – not in the way that Americans are, for example, given the country’s history of slavery. Then there is the fact that Italy itself has long been seen as a country of mass emigration – Italians have historically been, and continue to be, subject to racism abroad. “But if anything, I believe that racism is more complex on this side of the Atlantic,” said Uyangoda. “The main difference between Europe and the US is that for a long time, Europeans practised their racism abroad,”

Practised on their own citizens, too. In Wasted Lives: Modernity and its Outcasts, the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman writes that Europe’s colonial powers, including Italy, have long dispatched unwanted citizens to its colonies. These citizens were classified as “economic migrants”: scroungers from the welfare state, disturbers of the peace (or, more accurately, of industrialists). After a series of socialist strikes across Italy in 1898, for example, Italy deported poor southern “dissidents” to Eritrea.

Today, however, the Italian mainstream media seems more concerned with debating the ills of cancel culture than with investigating the country’s racist past and present. Debates over historical monuments – from the Milanese statue of Montanelli, the journalist who admitted to buying a 12-year old Eritrean bride in 1969, to Rodolfo Graziani, a fascist war criminal famous for deploying chemical weapons in the battle of Amba Aradam in Ethiopia – rage on across the airwaves, while the Racial Laws of 1938 or the fact that Mussolini’s grandchildren are still active in politics – go relatively unchallenged.

What now for Italy?

The migrants who have been banging at the gates of Fortress Europe have exposed the contradictions at work in the self-proclaimed “land of hospitality”. These contradictions are only set to deepen. 143 million more people are predicted to flee Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and south-east Asia by 2050. Italy, with its geographical centrality on the Mediterranean, will be the first port of call for many.

“If Italy doesn’t start preparing the ground to welcome the inevitable future,” said Anthony, addressing the crowd in Bologna’s Piazza Maggiore, “We’ll find ourselves doing damage control within the next twenty years”.

Alice Figes is a journalist and master’s student of European culture and conflict at LSE.