Osime Brown’s Case Highlights the Ableism and Racism of the British State

by Ana Oppenheim

17 September 2020

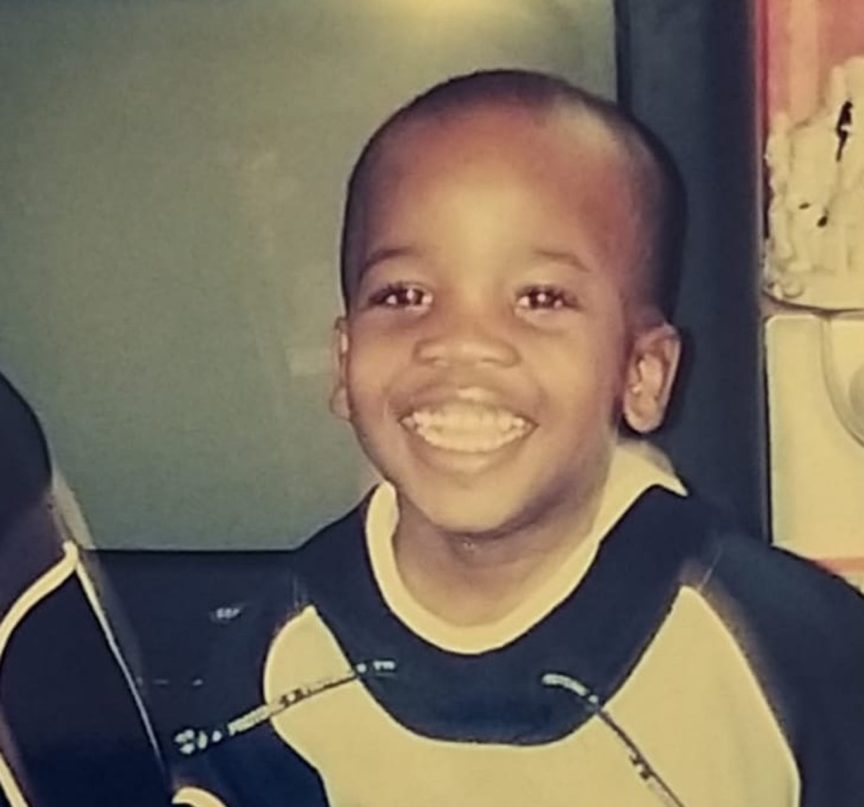

Osime Brown is 21. He grew up in Dudley, where he moved with his family at the age of four. He’s autistic, learning disabled, suffers from depression, PTSD and a heart condition. Soon, he could be deported to Jamaica, a country he has no current connection to or memory of.

Osime’s story exemplifies a long list of systemic injustices, faced on a daily basis by many across the UK. At school, he was described as disruptive and rude, his autistic meltdowns misinterpreted as tantrums.

Despite clearly struggling to keep up with his peers, he never received an assessment for his special educational needs. It was only after he was excluded at the age of 16 that his autism and learning difficulties were diagnosed. He’s since been estimated to have the mental capacity of a five to six-year-old.

Wrong place, wrong time.

After his exclusion, Osime was taken into care against his family’s will and moved from home to home 28 times over the course of one year. Soon after that, he was arrested and sentenced to five years in a young offender institution, having been seen with a group of people involved in a phone theft. A witness told his court hearing that he not only didn’t participate but attempted to stop the robbery. This, however, was not enough to prevent his conviction under joint enterprise law – a controversial legal doctrine according to which multiple people can be sentenced for the same crime if they’re deemed to be complicit.

Among those serving time for joint enterprise offences, Black people are overrepresented a staggering 11 times, and three times when taking into account the overall prison population – likely due to the stereotyping of Black male friendship groups as dangerous gangs. The court also failed to take into account how Osime’s autism might make him vulnerable to being drawn into activity that could get him into trouble.

In prison, Osime has suffered racist abuse, seen his physical and mental health deteriorate, had to undergo heart surgery (which him mum believes is linked to taking high dosages of antipsychotic medicine), has started self-harming and has subsequently been placed on suicide watch. He is distraught at the thought of being deported to Jamaica – a country he left as little more than a toddler, where he has no friends or relatives and no one to even pick him up from the airport. When he found out about the prospect of being deported, he asked which way he’d have to walk to visit his mother Joan. His family fears that he would not be able to survive on his own. “My baby boy is dying,” says Joan.

A lifetime of failings.

In every way except for his documents, Osime Brown is a British national. There is no other country he calls home. It was the UK’s school system that failed him, not recognising his disability despite obvious signs. Rather than being given support to finish his education, he was excluded – which is twice as likely to happen to Black students compared to the overall population and six times more likely to happen to students with special educational needs. In turn, pupils excluded from school are hugely overrepresented among young prisoners.

It was the UK’s social care system that endlessly moved him from place to place, resulting in lasting trauma. And it was the UK’s criminal justice system that imprisoned him for a crime he didn’t commit, with no consideration for his well being or future. Now, the UK is trying to abscond responsibility for this series of failures by sending him abroad with no hope of return.

Under UK law, any foreign national sentenced to more than 12 months will be automatically deported after leaving prison, unless serious reasons are provided for why this would not be in the public interest. For those with sentences longer than four years, exceptions can be made, but only in extremely rare cases, when there are “very compelling circumstances” that mean a deportation should not go ahead. Severe health problems and disability can, but don’t have to be, considered “compelling” reasons, and in Osime’s case were deemed insufficient. Currently, he’s due to be transported to a detention centre on 7 October, where he will await deportation.

The struggle doesn’t end with Osime.

Earlier this year Osime’s family, their friends and allies, set up the Justice for Osime Brown campaign, organising protests and encouraging supporters to write to their MPs. Meanwhile, the petition to prevent his removal has so far gathered over 35,000 signatures, with the cause attracting the support of Neurodivergent Labour and its patron MPs John McDonnell and Nadia Whittome. Campaigners are hoping that, with enough public pressure, the Home Office will reconsider its decision.

Osime’s fate might be decided within weeks but the struggle can’t end there. His heartbreakingly unjust case presents a vital starting point for a whole series of national conversations about the institutional racism and ableism he has experienced at every stage of his life – from the educational system to social care, the criminal justice system and prison, to finally the barbarity of the UK border regime.

Important questions must be asked: why are people who already served their time being punished twice just because of where they happened to be born? Why, after the experience of Windrush, are we still deporting people who arrived in the UK as children?

Black, disabled and with the wrong passport, in the eyes of the government, lives like Osime’s are expendable. If it wasn’t for a skilled and passionate group of activists determined to keep him in the country, we would never have even heard his name. How many others like him are there, who have suffered injustice after injustice at the hands of the British state, without making headlines?

Migrant lives matter.

As the Black Lives Matter movement spreads across the world, demanding an end to systemic racism, the UK government is instead pushing back against it: extending stop and search powers, pushing for tougher prison sentences and considering opting out of parts of the European Convention of Human Rights to speed up deportations. Meanwhile, the Home Office is launching attacks of its own, recently putting out a video on social media – which has since been taken down, following criticism from the legal community – accusing migrants’ lawyers of being “activists”.

We owe it to Osime to fight like hell for things to change – not just for him, but for all the other Osime Browns whose stories we’ll never hear. To all those who fall through the cracks of a broken system; who the state would rather expel, lock up and deport than take responsibility for. Their lives matter.

Ana Oppenheim is a member of Momentum’s National Coordinating Group and a co-founder of the Labour Campaign for Free Movement.