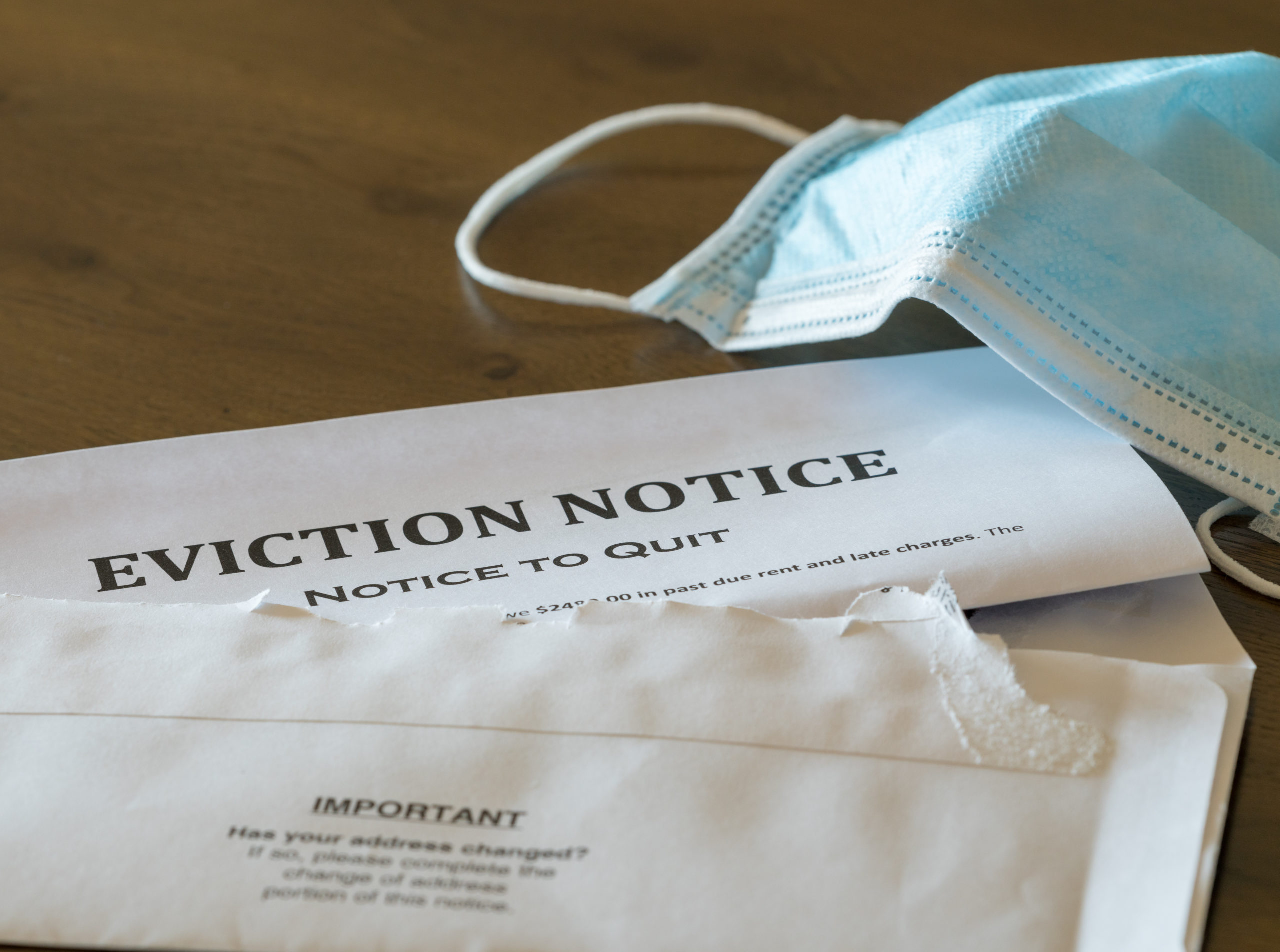

‘It Scares Me to Think Where We’ll End Up’: The Renters Facing Homelessness Now the Eviction Ban Has Lifted

by HG

23 September 2020

The eviction ban brought into force in March has provided temporary shelter to the thousands of renters who have been financially affected by the pandemic. However, the lifting of the ban on 21 September could now see thousands made homeless. Novara Media spoke to some of them, and to the people fighting for their right to a safe home.

“It scares me to think where we’ll end up. The whole thing is terrifying.” When Katie* was served with a Section 21 (or “no fault”) eviction notice in May, the ban the government introduced two months prior meant her eviction could not be carried out. However, with the reopening of the housing courts, Katie and her family – who aren’t able to move into their new property until Christmas – find themselves facing the prospect of homelessness during a global pandemic.

Katie’s story is far from an anomaly. National housing and homelessness charity Shelter have reported that over 300,000 people are in rent arrears as a direct result of the pandemic, making them particularly vulnerable to eviction – Section 8 notices can be served on tenants with over two months’ of arrears. As the eviction ban ends, some 55,000 households risk being made homeless.

The eviction ban has ended. It’s now crucial the government provides struggling renters with emergency funding to help them clear Covid arrears.

The eviction ban has ended. It’s now crucial the government provides struggling renters with emergency funding to help them clear Covid arrears.

Join us as we continue to press them to ensure people have safe and secure homes. https://t.co/oNkp5fQAun

— Shelter (@Shelter) September 21, 2020

Having been unable to work since November because of major surgery, Katie says that her landlord, who is aware of her medical situation and her two young children, has been “vile and completely harrass[ing]” – to such a degree that Katie contacted Shelter and a solicitor.

Now that the eviction ban has ended, the threat of having nowhere to live is becoming very real for Katie and her family. Unable to move in with elderly relatives, who are at high risk of coronavirus, they are also prevented from viewing new properties due to local lockdown rules in Manchester.

Unsurprisingly, Katie says that the experience has taken a toll on her family. “It’s caused huge rifts,” she says. “Luckily the kids are just excited for a new house and school, but I’m stressed as we don’t have the money to move and also run the risk of the kids being split up to go to new schools where there are spaces.”

‘We can no longer to afford to live in the place my kids were born and raised.’

Facing eviction from their home of 13 years in south-east London, Craig’s family of five is in a similarly difficult position. Although they have been given six months notice, their landlord has increased their rent by £500 a month, in what Craig claims is a bid to force them out sooner.

The couple, who are both currently employed due to Covid-19 are trying to contest the raise at a tribunal, “but have no idea what they will decide”.

With their eviction deadline looming, the family is faced with the prospect of being priced out of the area in which they have made a life. “The whole situation has put a strain on every aspect of our life,” explains Craig.

“We can no longer afford to live in the place where my kids were born and raised, and where my wife has grown up.

“The feeling of instability has affected my kids’ schoolwork – one is starting her GCSEs – and their overall morale. It’s a horrible situation to be in, especially since we’ve been great tenants for 13 years, never missing paying our rent or damaging our flat.”

In this uncertain climate, activists, campaign groups and renters unions are calling for greater protections for private tenants – especially in cities, where the number of people experiencing homelessness was rising even before the pandemic hit.

‘It can be a very short journey to homelessness after being evicted.’

In Oxford, a city in which eviction from the private sector is the top cause of homelessness, organiser Lucy Warin explains how “we’re already hearing of an increase in approaching Oxford City Council to access homelessness services as a result of the pandemic.”

For Warin, who organises with the Oxford Tenants Union, it is essential that renters not just in Oxford, but across the country, are protected now, in order to avoid a huge spike in homelessness in the coming months.

“For those renters with low or precarious incomes, with no savings, or with few family and friends close by it can be a very short journey to homelessness after being evicted – a journey further shortened by the pandemic,” warns Warin. “Keeping people in their rented homes is the frontline in the fight against homelessness, during and beyond the pandemic.”

Across the housing and homelessness sectors, a sharp increase in homelessness as a direct result of the pandemic is a real threat. Head of Public Affairs at Centrepoint, Paul Noblet, confirms this: “All the indications are that these worrying trends will deepen and, without support, more people will lose their homes”.

For Noblet, one of the most pressing concerns is that young people will struggle to navigate the eviction process and find alternative accommodation. “Arrears and evictions are expensive and a failure to support those affected during the pandemic risks shackling them with debt and, in some cases, homelessness for years to come,” he explains.

The immediate solutions to preventing such a crisis, Noblet says, are obvious. “No one is asking ministers to reinvent the wheel here. The crisis could be avoided, as it was in March, simply by ensuring that either the ban remains or robust alternative support is available for those who need it.”

‘It’s time to put an emphasis on living quality.’

Taking a broader view, chief executive at the Centre for Homelessness Impact, Dr Lígia Teixeira, argues that “a clear, evidence-informed plan” needs to be implemented to effectively tackle the issue. Texeira urges that there be an immediate “fulfil[ment] of the Conservative party’s commitment to abolish no-fault evictions…dedicated investment in the creation of genuinely affordable homes in the right places… [and] financial support…for those who need it – both tenants and landlords”.

Building on this, Warin calls for longer-term regulations to be brought in to replace short-term pandemic protections, such as increased action from local services and the cancellation of rent debt. “We need local authorities, charities, support services, campaigns and unions to work together, keeping people in their homes for the sake of public health during and far beyond the threat of the virus,” she says.

Meanwhile, for renters like Craig, beyond the immediate measures that need to be taken to protect them, the pandemic has also brought the need for a realignment of priorities around property and homeownership sharply into focus.

“Well, immediately I’d like to see the government do what [London mayor] Sadiq [Khan] is asking and freeze all rent increases for the next two years and also shift the power of rights, from [those] capitalizing on property development to the renters and families just trying to live in these cities,” says Craig. “It’s time to put an emphasis on living quality and culture rather than capital gains.”

There is a glimmer of hope, however. In a last-ditch attempt to protect renters, Lib Dem peer Baroness Grender is set to propose a motion in the Lords later today to stop evictions from going ahead. Craig and Katie will be hoping she is successful.

*Identifying details have been changed to protect anonymity.

HG is a freelance writer.