Disabled People and Care Workers Must Build Common Cause in the Fight for Better Conditions

by Jamie Hale

24 September 2020

The care industry has complex power dynamics that make organising and unionising a challenge. It contains a workforce that is underpaid and often multiply marginalised – low-paid, BAME, usually women, and often migrant workers – but also a class of disabled people reliant on that same workforce.

Where one of those groups is exploited, the other group is also exploited. But the left needs to recognise it has obligations beyond those owed to the workers in this situation – it also has an obligation to the disabled people reliant on those workers. If we ignore the complexities of this relationship, we risk undermining and disempowering the people dependent on carers to meet their daily needs. If our overarching goal is dignity and liberation for all, we need to develop a model of organising that builds and develops solidarity with care workers and disabled people alike, and doesn’t advantage one group to disadvantage another.

The political economy of care.

Before we can build such a model, it is necessary to understand the funding and employment models in the industry. Care funding comes from three primary places – local councils, the NHS, and self-funding (people paying for their own care, themselves). To simplify the picture somewhat, if that funding comes from councils or the NHS, it generally happens in one of two ways – commissioned care and direct payments.

Commissioned care packages are those where the funding body organises a person’s support. This might be directly with a care agency or care home, or it might be as part of a block booking, where all care packages for a certain area are handed to the same care agency. Where a commissioned care package is in place, whether via a care home or care agency, a business (usually, although some charities work in this model too) is trying to make a profit by taking more money from the funding body (and any self-funders who use it) than it spends on providing care. This business has the power to hire and fire, to set wages, and functions to some extent within market forces, although its primary client is usually local funding bodies.

When a disabled person receives care from a care home or care agency, they have very little control over their care. They may have no say in who comes into their home to provide their care, they may have little say over what time it happens, and they’re likely to have no say over what’s done within that time – as the ‘care plan’ is paramount, regardless of how appropriate it is. There is little-to-no recourse for this person if they’re unhappy with the care they’re receiving.

Similarly, an employee in this situation has very little power. They may still legally be paid a flat rate for sleep-in shifts (I’ve seen as low as £30 for the whole night), they may be out of the house working for 14 hours a day and earn less than £4 an hour once time travelling between people’s houses is taken into account. They may be expected to do 15-minute care visits, and told that if they stay any longer, the extra time will be considered voluntary and therefore unpaid.

With the disabled person potentially allocated funding for far less time than tasks normally take, the care worker is trying to fit everything in, and risks running increasingly late without being paid for the extra time tasks take. Meanwhile, each delay impacts the next care recipient, who might have relied on the carer being on time so they can get to work themselves, risking their employment. Across social care, the gulf between what is needed and what is received is significant – both for disabled people and for carers.

Using a care agency, I’ve been supported by staff who’ve never met me before, staff I don’t share a common language with, staff arriving anywhere in a 2-hour timeslot, homophobic staff, racist staff, even staff who pray to heal me. Agency care creates an abusogenic environment – one in which carers have total power over the disabled people who rely on them, and one where those disabled people have little recourse. Of course, this is not to deny that agency carers are also often abused too, both by unscrupulous employers and by care recipients themselves.

When battling care homes and agencies, legal cases like that brought by Unison on the minimum wage, or the back-and-forth that took place over sleep-in shifts, are one tool the unions have. While care agencies and homes will always say they could go bust under rulings like these, in practice if they did the government would have to step in to ensure some continuity of care. But working-to-rule and striking – other tactics available to unions – hold considerable risk for the disabled people being supported – who might then have needs unmet, or met by staff who know nothing of them or their needs. There are often no alternative options for people reliant on agency care, but nonetheless, such measures remain core tactics by which a worker can challenge the power of their employer. But what about when there is no big employer?

The politics of direct payments.

Direct payments are a funding model whereby social services or the NHS devolve funding to the individual. Rather than the funding body paying an agency, direct payments go to the individual to decide how they want to receive the care, and from who. They might commission an agency themselves – giving them more power than if the agency is commissioned by the funding body, because they can transfer their care to another agency – or, increasingly frequently, they become the employer of their own carers. In that situation, the employees are often referred to as personal assistants, language that reframes the dynamic from a benevolent, paternalistic model of ‘care’ to one of people employing assistants to meet their needs in the way they see most appropriate.

Many older people prefer to remain with commissioned services. They require far less in terms of responsibility, and are far less complex. However, for disabled people willing and able to take on the work of becoming an employer (for me, it’s around 15 hours a week, more when recruiting), there are considerable benefits. Being able to freely choose the people involved in your intimate personal care should be a human right, and is certainly a matter of consent. Being able to decide what time you get up and leave for work, being able to tell someone who is being homophobic towards you that they’re breaching their contract of employment, deciding what you want to eat (even if it’s not on your care plan) – these are issues of independence. Direct payments make it possible to recruit staff, set their hours, workload and management, and to pay them directly. In this scenario, the disabled person is the legal employer – but we ought to raise questions about whether this relationship is easily comparable to standard, exploitative models of employment.

The traditional trade unions are generally not in favour of the direct payments model. Typically, their hope is to build a union-dense workplace which could then raise demands against the employer with the threat of strike action. For disabled people using care agencies, the prospect of labour being withdrawn is risky enough; for people on direct payments, there may be no contingency if their whole team was to withdraw its labour. Going into the home of someone on direct payments to organise their three PAs would be a breach of their privacy, dignity and independence – and would do nothing to improve the position of PAs beyond that atomised workplace. But the problem is that the individuality and hyperlocality of each direct payments workplace doesn’t fit with many trade unions’ preferred organising approaches, and the fact of employment via direct payments requires a creativity and flexibility of approach that is often lacking within the labour movement.

Being critical of the personalisation offered by direct payments, unions typically see their duty and accountability as being to their member workers, rather than to oppressed people more broadly. This is clear in Unison’s guide to personalisation in the workplace where the “increase in [the] agency and PA workforce” is a key issue – as if care agency work (for private business) and PA work (for an individual employer) were comparable in terms of exploitation. Unison suggests local authorities should use a “single PA register to vet and train all PAs” and “directly employ a pool of PAs whom service users can select from”. Yet this completely undermines the choice and control offered to disabled people (and PAs) by direct payments – it is a paternalistic assumption that we can neither vet nor train our PAs, and shouldn’t recruit freely, choosing the person to best meet our needs under the employment structure that works best for us. Significantly, the proposal also undermines the idea of consent, and that we should be able to choose who provides us with intimate personal care.

While the ‘partnership models’ promoted by Unison towards the end of the guide sound promising in terms of joint campaigning for better wages, funding and training, the wider context and the language used in the guide mean it doesn’t seem like an especially constructive effort to reconcile the (very real) issues facing disabled people with the needs of the workforce.

It does little good to set funding bodies, direct payment recipients and PAs against one another, in the context of a relationship in which no party has real power. Within the direct payments system, the wage is often set by the funding body, and a frequent complaint of direct payment recipients is that they wish they could pay their PAs more to improve retention. Relatedly, direct payment recipients may not be allowed to vary the hours offered, and may be required to use a zero-hours contract (so that if they’re admitted to hospital, for example, the funding body can stop paying for their care). Recipients are frequently funded for far less time than all their care would actually require, forcing a very time-pressured workload onto PAs. Yet for their part, funding bodies – especially local councils – are often under huge financial pressure, even when adult social care is an enormous part of their budget. They have no power to alter how direct payment recipients treat their employees, while the PA, of course, is a low-paid employee in a workplace where there is potentially little hope of progression, and where the conditions are set by an employer – the disabled person – who may have little experience in employment.

Yet direct payments offer a huge opportunity for disabled people and care workers to build collective solidarity and challenge the inequalities in the system. We make no profit from the surplus labour of our employees, and without being able to pay better we can only be the most ethical employers we can be, in a challenging environment. Our employees may well get better pay and conditions with us than they did an agency – and have far more power to effect changes for the better where it’s on a 1:1 basis with an employer than they would with an agency.

Uniting for common benefit.

It is in all of our interests that disabled people have adequate care hours, to reduce time pressure on both them and their assistants. It is in all of our interests that people are properly trained, skilled, and have access to training, as well as personal and professional development. It is to all of our advantage if people are well-paid for the work they do, if they feel respected and valued. It is also to all of our benefit if disabled people receive adequate equipment to meet our needs, if we have access to training in HR and management, health and safety, and workplace best practice. Without a profit motive, in many ways I see my work with my PAs as that of colleagues – I don’t have the position of an employer – there is no income in this for me, there is only my continued independence.

Organising carers against disabled people would do nothing to leverage power against the only people who can affect the real terms and conditions of the industry. By following the money, we can see that oppression and underpayment are often forced by the privatisation of care by agencies, and the limited funding afforded to councils and the NHS to meet the ‘grey tsunami’ of need. But organising against central underfunding will be ineffective unless it’s done by care workers and disabled people in concert, with pressure from the NHS and councils on central government to resource them adequately.

We must agree key demands that meet the needs of both disabled people and PAs, and we must collaborate to fight for our common benefit. This might mean meetings that bring together two communities that may be distrustful of each other, each seeing the other as a potential abuser of the complex power dynamics in the situation. But highlighting demands that benefit everyone is crucial, as is experimenting with methods of protest that do not risk harming disabled people through a withdrawal of care. Such methods of protest might be hyper-local – such as responding to an especially exploitative agency – or they might be designed to focus on media optics – something Disabled People Against Cuts do excellently – or they might be protests of noise, or publicity, or campaigns. I don’t pretend to know the most effective ways of demonstrating in this environment, but if we can’t find a way to leverage power that doesn’t balance the needs of both disabled people and the care workers supporting us, then it will do nothing to further the aims of oppressed people as a whole.

Only once we have built organising structures that bring together carers working in the atomised environments of direct payments, as well as in agencies, and when we are supporting the disabled people who use care services in our movements (not forgetting that many carers will have chronic health conditions and be disabled themselves) can we find ways forward that rely on solidarity between all parties, and a shared commitment to advancing dignity in work to carers while supporting disabled people with dignity in their lives.

Jamie Hale is an expert in health and social care policy, and a poet and writer. They have employed a team of PAs for a decade.

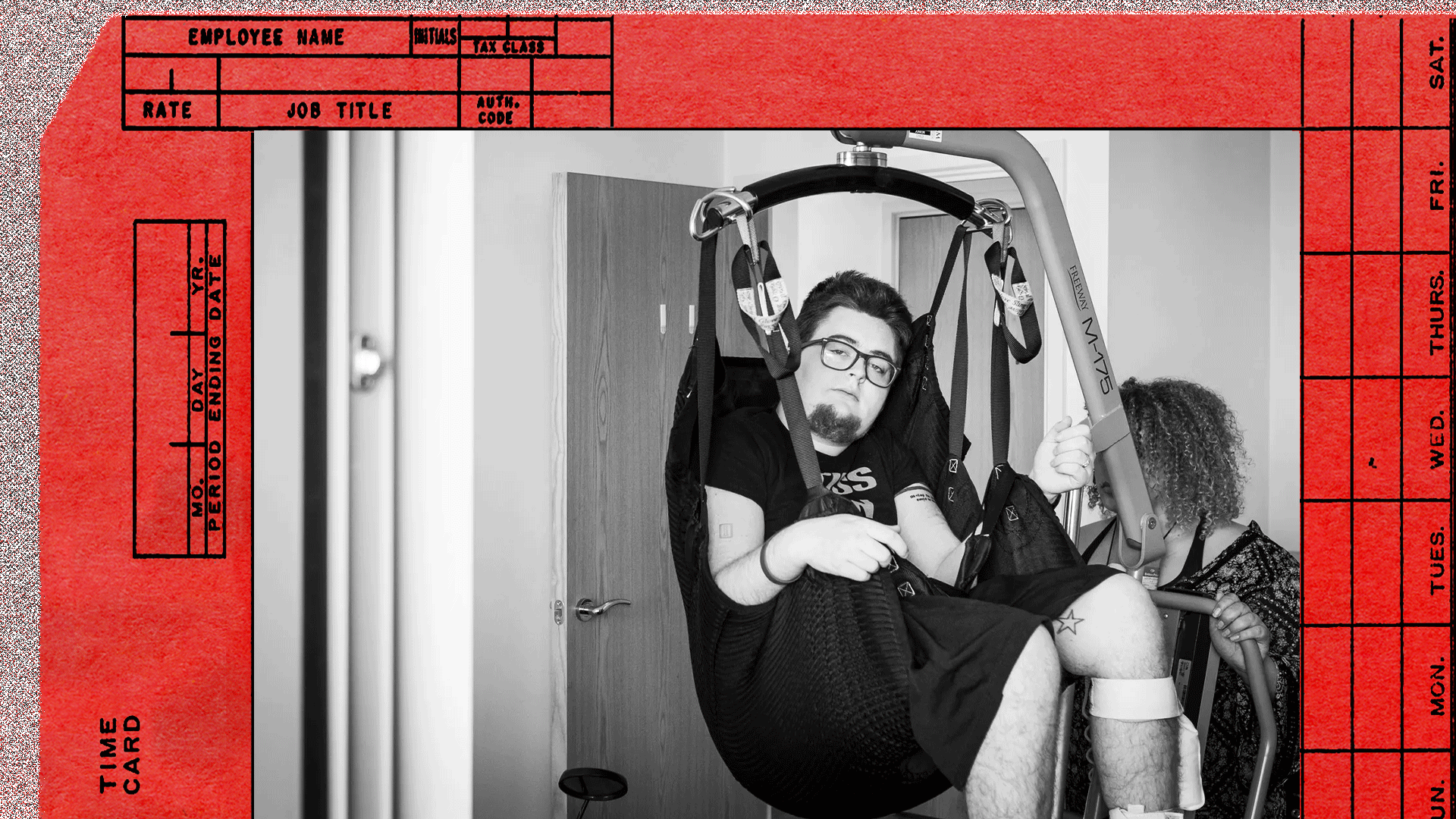

Photograph courtesy of the author. Credit: Benjamin Gilbert/Wellcome Collection.

- The Future of Work focus is part of Novara Media’s Decade Project, an inquiry into the defining issues of the 2020s. The Decade Project is generously supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (London Office).