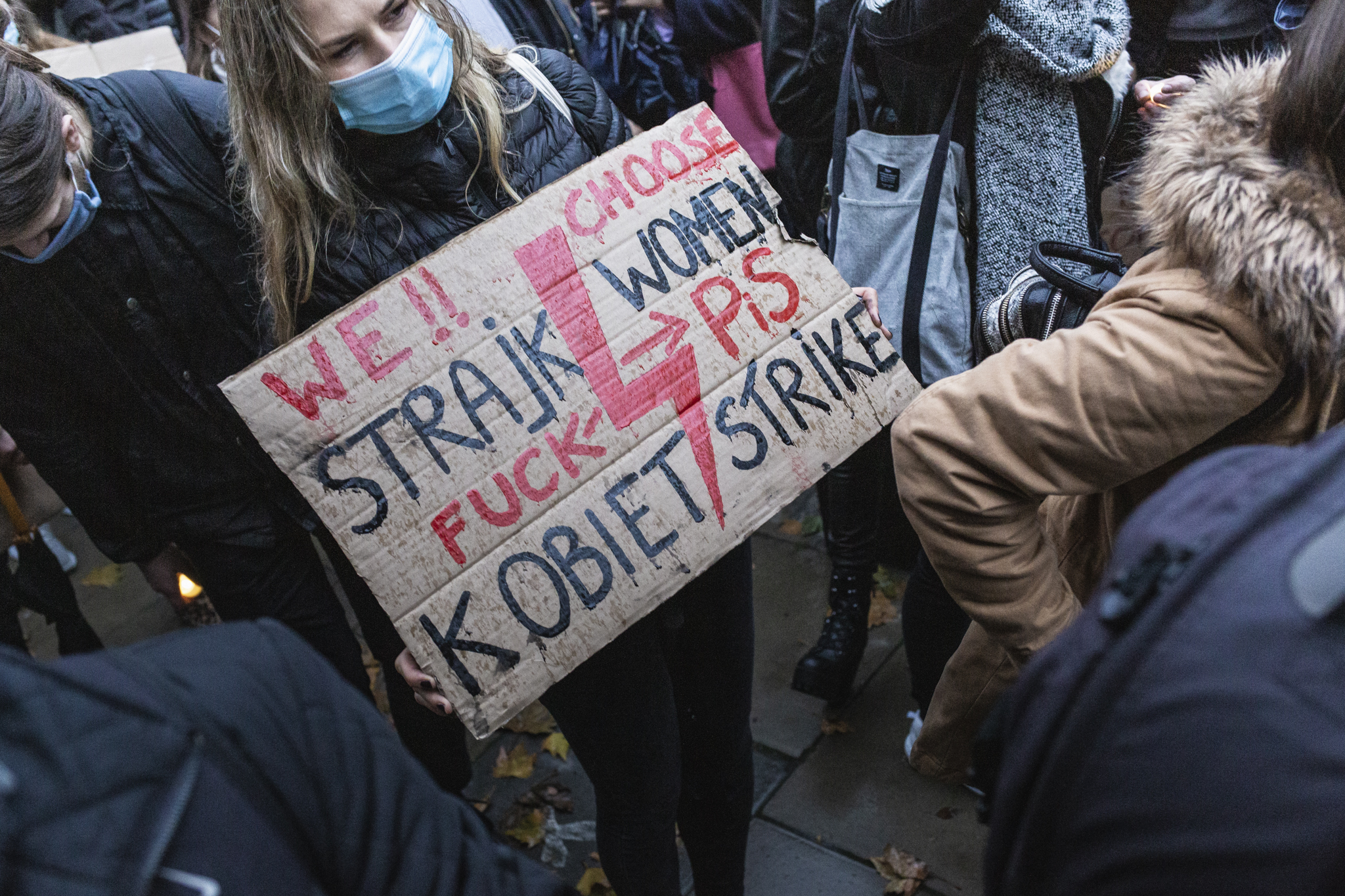

Thousands of people took to the streets last week after Poland’s top court passed a ruling to outlaw nearly all abortions. Since then, demonstrations have spread across the country, with hundreds of thousands of women and their allies marching across towns and cities, blocking roads, defacing monuments and clashing with police.

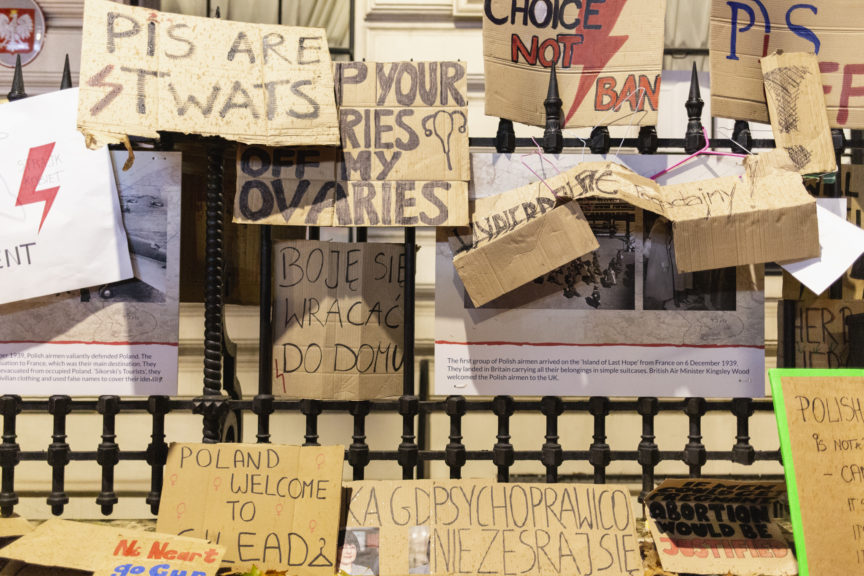

On Sunday, activists targeted churches, carrying in placards and interrupting services. On Wednesday, thousands participated in a national women’s strike, skipping work for a day to express their opposition to the ban. Polish women have made it clear that they’re done with politeness. “Wypierdalać” – meaning “get the fuck out” – is the rallying cry heard at marches up and down the country. Out of our ovaries, and out of government.

Even before the ruling, Poland had some of the strictest abortion laws in Europe – allowing a termination only in cases of rape or incest, a threat to the pregnant person’s health or severe foetal defects. In reality, the third exception has accounted for around 98% of the 1,000 legal abortions happening in Poland each year. The official statistics of course don’t take into account the large number of abortions that happen illegally or abroad, estimated at around 100,000 a year. Women who can afford it travel to access a safe termination in British, German or Czech clinics. Those who can’t, resort to home methods, often risking their lives to end an unwanted pregnancy.

Since the ultra-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party came to power in 2015, church-allied far-right campaigners have made multiple attempts at further restricting reproductive freedom. Before last week, the closest they had come to succeeding was in 2016, when PiS agreed to vote through a motion to completely outlaw abortion. Mass protests across the country forced the government to withdraw support right before the final vote, but pro-life campaigners did not give up. This time, they opted for a new strategy – a legal case submitted to the constitutional tribunal.

The Polish constitutional tribunal has been at the centre of a heated political battle since PiS came to power in 2015 and quickly annulled the appointment of five judges, instead packing the court with their own appointments. Over the past five years, PiS has made further moves to undermine the independence of the judiciary. Sensing an opportunity, a group of PiS and other rightwing MPs submitted the current anti-abortion case to the tribunal. It succeeded. Now, unless the ruling is overturned, women will be forced to give birth to children with no chance of survival.

In the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, with a severe second wave forcing Poland to implement tight restrictions, one might assume that social unrest would be easier to contain. However, those who hoped to get away with banning abortion without a backlash have quickly been proven wrong.

What’s remarkable about the protests, which have now raged across Poland for over a week, is not just their energy and militancy. It’s also the broad cross-section of society they attract. It’s not just liberals in major cities who are out in the streets. It’s also middle-aged mums in small towns and churchgoers in PiS heartlands. Several hundred joined a protest in Lądek-Zdrój, a town with a population of 5,500. A thousand turned out in Sompolno – around one in 10 of the urban-rural district’s inhabitants. Hundreds also marched through Limanowa, a small conservative town where over 80% of voters recently supported PiS-backed President Andrzej Duda – and the list goes on.

Alliances of feminists and trade unionists are a rare sight in Poland, but organised farmers, taxi drivers and postal workers have joined the demonstrations across the country, which have even been formally endorsed by a miners’ union, among others. Despite pundits’ claims that the ruling has “divided Poland”, in this case the nation appears remarkably united: opinion polls show that nearly three-quarters of the public oppose the ruling, with just 13% in favour.

Paradoxically, attempts to further restrict abortion access appear to have strengthened Poland’s growing pro-choice movement. For decades, few had the courage to tinker with the 1993 law – a painstakingly reached agreement between state authorities and the influential Catholic Church, commonly referred to as the “abortion compromise”. For a long time, despite a minority of campaigners on both sides demanding to be heard, the debate around abortion seemed closed. By undermining the “compromise”, pro-life die-hards threw it open again, inadvertently making space for advocates of full reproductive freedom to finally get a hearing.

This year’s mobilisations were enabled by the fact that pro-choice activists didn’t have to start from scratch. The 2016 “Black Protest” created a lasting movement infrastructure. In many cities and towns, opponents of the ruling party could tap into existing networks – in some places dormant and waiting to be brought back to life, in others, active in the form of feminist groups that have spent the past four years organising and agitating. A number of initiatives have emerged since the last wave of protests, from the Ratujmy Kobiety (Let’s Save Women) project whose motion to liberalise abortion law was debated in parliament, to Abortion Dream Team, a high-profile campaign aiming to destigmatise abortion and provide assistance to women seeking one. Despite fierce opposition, the call for free abortion on demand is fighting its way into the political mainstream.

The rebellion against the abortion ban – born in 2016 and revived now – is arguably the single biggest social movement Poland has seen since workers’ movement Solidarność. Countless women across the country, many of whom never before saw themselves as activists, are learning what it means to defy authority and stand up for their rights. We don’t know yet what the immediate outcome might be, with feminists facing a tough battle against a politicised judiciary and an ideologically-driven, intransigent government. But one thing is clear: this moment is radicalising a generation. For many Polish women, there is no going back.

Ana Oppenheim is a member of Momentum’s national coordinating group, a co-founder of the Labour Campaign for Free Movement and member of the Polish leftwing party, Razem.