Every four years, we Brits engage in the parlour game of debating what the US election means for us. This year, more than any other, we seem particularly unsure. Ultimately, this has as much to do with doubts about what the UK now represents, as about the intentions of the next inhabitant of the White House.

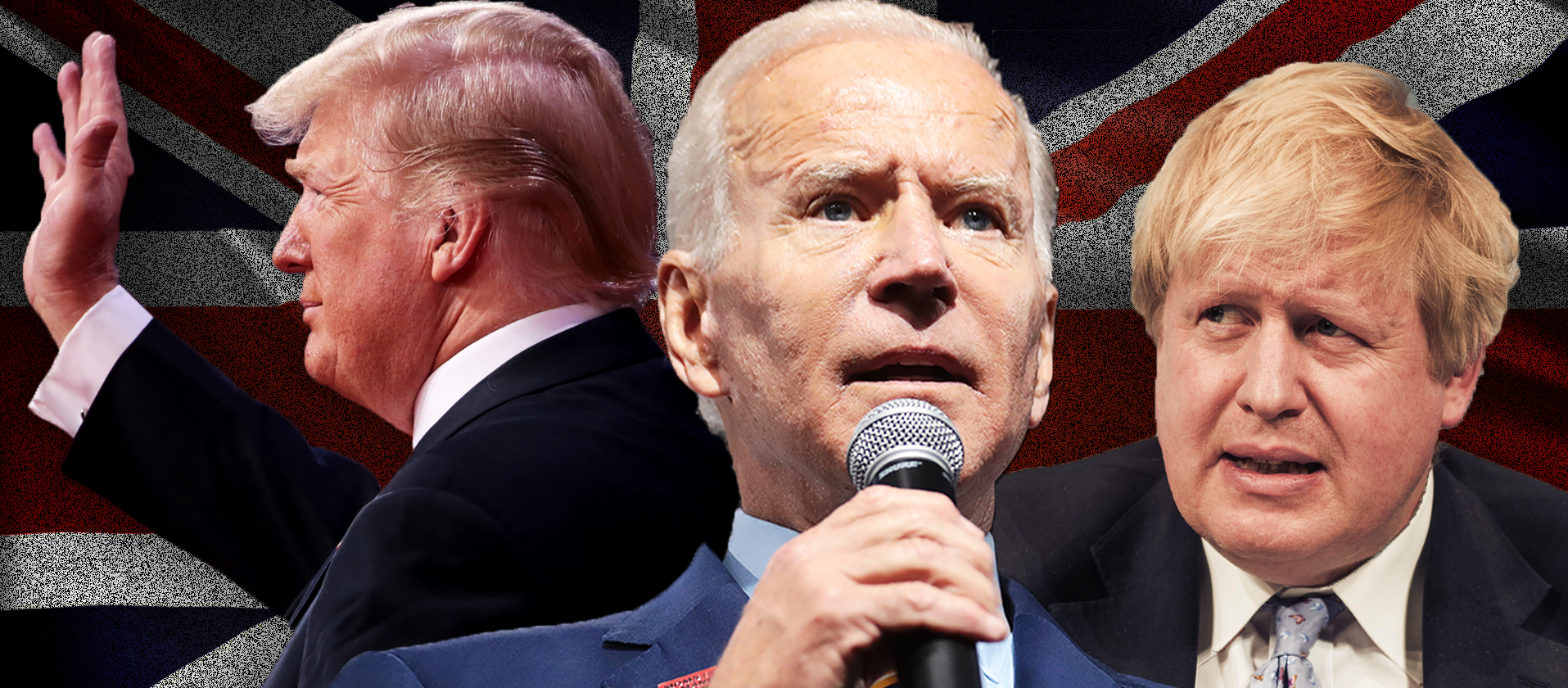

The implications of this American election will hinge not only on who triumphs, but on the ambitions of Boris Johnson’s government. Viewed one way, the prime minister is a natural soulmate of president Trump, a disrupter intent on tearing up and rewriting the rules of the game.

Talk of a no-deal Brexit, of ignoring our commitments under international law and of taking on various aspects of the British establishment (the courts, the civil service, the BBC, etc) speak to a populism that would be easily recognisable to the current incumbent in DC. Not for nothing did Trump hail the prime minister as “Britain Trump”.

With that said, there are emerging signs that Johnson does not intend for his domestic revolution to extend to the world stage. There have, moreover, been some indications that a period of profound parochialism — as parliament and successive governments struggled with Brexit and then the pandemic to the virtual exclusion of all else – is coming to an end.

Judging by the government’s reaction to the new security law in Hong Kong, its stance on Huawei’s involvement in the national 5G network, its imposition of ‘Magnitsky’ sanctions on a number of foreign individuals, its stated ambitions for the UN COP26 summit next year and its talk of creating a ‘D10’ alliance of democratic states, it would seem that, Johnson intends to try to carve a role for ‘global Britain’ as an active defender of the liberal international order.

Needless to say, the outcome of Tuesday’s vote will have a significant impact on those ambitions. At a uniquely politically polarised moment in the history of the United States, the identity of the next president will have a profound impact on the future of the global economy, of multilateral institutions, of efforts to combat climate change and the strength of the transatlantic alliance.

Whatever that outcome, the combination of Johnson’s radical — some would say populist — internal agenda, with an apparent desire to act internationally in defence of a liberal world order, will create problems.

A victory for Donald Trump would, in some sense, serve to reinforce faith in Johnson’s populist agenda and his pursuit of Brexit. Yet good relations with Trump has not, to date, borne anything in the way of tangible benefits. Theresa May was the first foreign leader to visit the president. Johnson apparently enjoys a close relationship with him, yet Trump responded by interfering in British politics, in the Brexit process and by accusing British intelligence of spying on him.

They will soon be calling me MR. BREXIT!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 18, 2016

Trump has also done the UK no favours when it comes to negotiations over trade deals. Indeed, James Forsyth, a journalist supportive of the government, has admitted that Trump’s support for Brexit has been more rhetorical than practical.

And when it comes to a wider international agenda, the president’s suspicion of multilateralism, his ‘America first’ agenda and his contempt for attempts to address climate change will make him a far harder partner than his opponent.

The fact of the matter is that on foreign policy issues, Johnson is closer to Biden than he is to Trump. The Democratic candidate will want to work with like-minded partners, and would be far more positive about NATO than the incumbent. The former vice president has said he will rejoin the Paris climate agreement (which the US is due to leave the day after the election) and push for more ambitious targets. The Democrats share the weariness about China increasingly exhibited by the British government and there are signs that the idea of a D10 has gained some resonance in Biden’s team.

The problems with Biden, however, are the mirror image of those of Trump. While their foreign policy objectives might be aligned, Brexit has caused a rift. Many in Biden’s team still seethe at remarks made by Johnson about Barack Obama’s Kenyan ancestry. In December 2019, the candidate called Johnson a “physical and emotional clone” of president Trump. There seems little doubt that the priorities of a new Democratic president will be to build relations with Paris and Berlin rather than London.

Be this as it may, there are still good reasons to assume that both governments will overcome whatever suspicion there might be to work together. Of course, the special relationship has long since ceased to be as special as British observers have been inclined to claim. From American annoyance at what were seen as disappointing UK contributions to conflicts in Basra and Helmand, to irritation about David Cameron’s handling of the debate over intervention in Syria, the Washington establishment has come to realise that there are limits to what the UK can contribute in terms of military assistance. As one acerbic observer put it, the “Rolling Stones can fill London’s Wembley Stadium; the British Army cannot”.

Yet one should not overlook the deep ties that bind the two sides of the Atlantic on military, diplomatic and intelligence matters. Moreover, the coming year holds real possibilities for British diplomacy. The UK takes over the chairmanship of the UN Security Council from February and will be hosting the G7 summit next year. It will also host the 26th UN Climate change conference in Scotland next November.

Meanwhile, talks are underway about using the G7 summit to launch the so-called D10 grouping of democracies (the G7 plus South Korea, India and Australia).

The UK is hoping to play a central role in the stewardship of the D10 via its presidency of the G7, so this is an area of potential fertile ground for cooperation (or, indeed, a test) between Biden and Johnson. UK also leading delayed Cop26, so it will be crucial ambitions align. https://t.co/Q0LcRVUm80

— Sophia Gaston (@sophgaston) October 25, 2020

Such an alliance could conceivably enable democracies to organise their resistance to authoritarian regimes, not least when it comes to key defensive issues like 5G and critical supply chains. The initiative would not only allow London to (finally) put some conceptual flesh on the bones of ‘global Britain,’ but allow it to act as a bridge between democratic states. And, crucially, it would also, as reports suggest, command the support of a Biden White House.

And so, for all the problems that might confront a Biden-Johnson relationship, there are at least some reasons to believe that the US and UK will be able to work together constructively in pursuit of shared international ambitions.

There are, however, limits to this. Not least that the US is no longer, and will no longer, be the kind of partner to the UK that it once was. This is partly because of shifting priorities that predate president Trump and which imply a greater reluctance to underwrite European security while asking for relatively little in return. A greater emphasis on European burden-sharing will outlive this presidency.

Perhaps more fundamentally, the fracturing of the foreign policy consensus in the US means that, whatever a president Biden may or may not do, a new administration could reverse it.

As three prominent scholars have argued, the disappearance of any shared American sense of identity, along with the polarisation that has made foreign and domestic, policy an object of partisan contestation – meaning an incoming administration would seek to overturn what its predecessor has done – shows that there is no longer any prospect of the US following long-term strategic ambitions.

Yes, we are probably right to worry about the outcome of an election in what is still the world’s most powerful nation. Ultimately, however, even if we can work effectively with whoever triumphs in that contest, our transatlantic ties will be far less secure than before.

Anand Menon is Director of UK in a Changing Europe.